By no stretch of the imagination could A. J. P. Taylor be called a conservative or tory historian. He would have been horrified (or, possibly, amused) by such an idea. A man of the left he was, though how far on the left varied rather.

By no stretch of the imagination could A. J. P. Taylor be called a conservative or tory historian. He would have been horrified (or, possibly, amused) by such an idea. A man of the left he was, though how far on the left varied rather.

He was very proud of the fact that he was the only invited historian at the Communist organized congress at Wroclaw in 1948 to challenge his hosts about history and its writing. On the other hand, he managed to support the Soviet Union in almost all his own writings and never quite managed to understand what Communism meant in reality.

Another thing about Alan (who was, as it happens, Tory Historian’s supervisor at Oxford) was his obsession with mischief-making, though some would call it trouble-making. He was very proud of this and thought this put him in the same category as a number of political and intellectual figures from the past whom he admired. Unfortunately, like all mischief-making, it was not always constructive.

Finally, one must point out the man’s innate conservatism. He came from a better off family than he pretended but saw himself as a representative of that most English sections of the population, the lower middle class.

It is this conservatism or proud Englishness that allowed him, when writing about Keith Feiling’s “A History of England”, to sympathize with the squierarchy, the bastion of Toryism:

“Toryism starts with the squire, the lesser landowner. Everyone knows that. Feiling emphasises again and again the permanent elements in rural society. He recognizes, as few Whig historians have done, the importance of local government; indeed even parliament bulks largest in his eyes as a gathering of country gentry. The traditional ‘liberties of England’ rested on law and custom, not on rational dogma, and the man who maintained them, as in Poland or Hungary, was the country squire. He maintained them no doubt for his own profit and advantage, a point which Feiling is inclined to slide over; still England would not be a free country without him.”The review, first published in 1950 and reprinted in the Penguin “Essays in English History” is of some interest, not least because of the assumptions of his time. Taylor seemed to assume that the Labour government was there to stay, that Conservatives were no more than a sizeable minority of the country (he does not specify what the other parties and their followers are) and deeply dislikeable. All this in 1950 just before a largely Conservative ruled half century set in.

The most interesting part is Taylor’s attempt to define Tory history. At first, he describes it as the Whig history without the ideas – Tories, in his opinion, being basically and deliberately inimical to ideas.

Then he goes further and comes up with an interesting definition. The Tories eventually accepted the 1688 agreement and, as the concept of devotion to the Crown and the Church of England gradually changed beyond what could be reasonably seen as Toryism, so the latter became the party of administration rather than ideology.

“If by Liberalism is meant all those who try to apply reason to politics, and who enter politics in order to improve things, then it is only tory landowners who are on the other side. Conservatism becomes the party also of those who are in politics simply to make things work: to promote, no doubt, their own careers, but to promote it by public service.”Like so many of Taylor’s ideas, this one sounds seductive, too. But it leaves out very many things, not least the notion that public service and its importance are also application of reason. It ignores or fails to perceive the flexibility of Conservative thinking and its ability to assimilate other ideas.

“Thus what may be called the Tory interpretation of history has no longer much to do with high-flown loyalty to the Crown or devotion to the Church of England: it is not even the exaltation of traditional institutions. The tory spirit in history is shown by an emphasis on administration, by getting ideas out of history and putting humdrum personal motvies and office routine in.”

Above all, and this is the strangest of all, it seems to ignore the growing importance of Socialist history and Conservatism becoming its alternative. (Well, sometimes.)

Lord Acton, the subject of the previous posting, was a great admirer of Leopold von Ranke. It seems fitting, therefore, that we should now publish what muat have been the latter's most famous comment about history:

Lord Acton, the subject of the previous posting, was a great admirer of Leopold von Ranke. It seems fitting, therefore, that we should now publish what muat have been the latter's most famous comment about history:

"You have reckoned that history ought to judge the past and to instruct the contemporary world as to the future. The present attempt does not yield to that high office. It will merely tell how it really was."There has been much discussion whether any historian can tell it "how it really was" and whether there is any possibility of objective (as opposed to honest) historiography.

It is, however, salutary to remember that the role of the historian is to tell and analyze not to pronounce judgements on the past, based on the ideology of the present.

Re-reading some of Lord Acton’s essays on history means reconsidering what one thinks one knows about him. Precisely why do we consider him to be the foremost conservative historian? The man was after all a Liberal MP, a friend of Gladstone’s who eventually made him a peer.

Re-reading some of Lord Acton’s essays on history means reconsidering what one thinks one knows about him. Precisely why do we consider him to be the foremost conservative historian? The man was after all a Liberal MP, a friend of Gladstone’s who eventually made him a peer.

He was one of the foremost historians of liberty, even though the proposed tome never saw the light of day and all we are left with is some superbly written and argued essays. Whether that makes him a conservative historian or not, his natural suspicion of power and of its accumulation does in my opinion.

Conservatives do not believe in utopian schemes because they do not entirely trust people. It is what made the Founding Fathers of the United States conservative, for instance. They carefully delineated structures that would prevent people from acquiring too much power on the assumption that anyone might use his (or her, though that was not an issue with the Founding Fathers) position to do so, unless restrained by social and political structures.

This is what Hugh Trevor-Roper (later Lord Dacre) wrote in his introduction to Acton’s “Lectures on Modern History”:

“The nineteenth-century belief in endless progress, the unwarranted assumption that man only needs freedom from ancient restraints in order to realise his inherent perfection, repelled him [Acton]. His view of human nature was not cheerful but dark: like Gibbon he looked back on history and saw the register of human folly, crime and misfortune, and therefore he believed firmly in ancient restraints. But he was not a tory. The ancient restraints in which he believed were not royal or priestly authority. They were the restraints of custom and society, local and personal liberties, that complex, organic tissue of slender, elastic filaments which saves man from sudden surrender to abstract ideas or arbitrary power and allows the slow growth of rational thought and practised freedom.”Acton had his own very personal problems with “priestly authority”, in particular that of the Catholic Church and the Vatican. Professor Trevor-Roper’s use of the word “tory”, however, might be considered to be somewhat outdated. There are not many thinkers or writers on that side of the political spectrum who unquestioningly accept “royal or priestly authority”.

To Trevor-Roper Lord Acton’s views and belief in the enumerated restraints that lead to the evolution of liberty indicated a whig and that is what he probably was in nineteenth century terms. In the twenty-first century, however, after the horrors of the twentieth, most of them created by ideologies that deliberately discarded ancient restraints, we can surely consider Acton to have been a true conservative.

Today’s anniversary is of an event that might not have looked particularly significant at the time but, in actual fact, began a process that changed the face of politics in this country for ever.

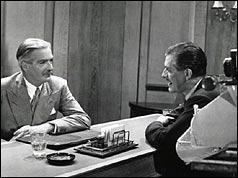

The Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden invited editors of national newspapers to 10 Downing Street and led a televised discussion as part of the 1955 electoral campaign.

“Sir Anthony was flanked by four ministers: the Chancellor, Rab Butler, the Foreign Secretary, Harold Macmillan, the Health Minister, Iain Macleod, and the Minister of Labour, Sir Walter Monckton.”The procedure seems to have been courteous with some sharp questioning by the editors, notably Hugh Cudlipp, who asked Eden about the common impression that he knew more about foreign affairs than domestic ones (with hindsight, perhaps, a questionable assumption).

Eden, it seems, reminded him of the nature of cabinet government. He himself may have spent more time on foreign affairs but he had always been part of a cabinet that also dealt with domestic matters.

“The programme was a welcome distraction in an election campaign which has been widely described as lacklustre, with one disenchanted journalist describing the early stages as "the lull before the lull".”All the political parties began to recognize the growing importance of TV and the dwindling importance of public meetings. And so, by stages we reached today’s situation when almost all politics is conducted on TV, the public meeting is a thing of the past with politicians rarely meeting anyone but carefully selected members of that public and even important announcements being made on the “box” rather than the House of Commons.

Probably the whole process was inevitable but one wonders whether Eden had the odd twinge of misgiving.

Having conservative correspondents in the United States has enormous advantages. One of them, Lexington Green, who has also commented on the blog, called my attention to a posting he did some years ago on Chicagoboyz.

Having conservative correspondents in the United States has enormous advantages. One of them, Lexington Green, who has also commented on the blog, called my attention to a posting he did some years ago on Chicagoboyz.

Lex periodically puts together a summary of his most recent reading matter and all of us rush off to the nearest library or second-hand bookshop to find the books he writes about.

One of the books he mentions in this posting is G.R. Gleig's “Personal Reminiscences of the Duke of Wellington”. This is not one of the great books of reminiscences about the Iron Duke but it is difficult to write anything consistently dull about the man.

There is a wonderful account of the Duke’s behaviour during the riots and disturbances that led up to the eventual passing of the Great Reform Act of 1832.

“He remained a tough old bird, long after he left the army. At the time he was opposing the Reform, there was a lot of "agitation" in the country, "mobs burnt towns and sacked gentlemen's houses". Gleig warned Wellington to be careful coming out to his country house. Wellington responded, "I suspect that those who will attack me on the road will come rather the worst out of the contest, if there should be one." Gleig, with a few gentlemen from the area rode out, each armed with "a heavy hunting whip, and pistols", to meet the Duke: "I found him in his open caleche, provided with a brace of double-barrelled pistols, and having his servant likewise armed, seated on the box." No mob emerged, so the Duke did not have to work the execution of any rustic miscreants with his own firearms.”One wishes that our legislators now had one tenth of the old boy’s courage and spirit. They might feel ashamed at the gadzillions spent on yet more layers of security that are being put up around the Houses of Parliament.

As MPs who demanded protection after the assassination of Spencer Perceval in 1812 were told, it is unmanly to crave security from the state if you chose to enter public life.

As MPs who demanded protection after the assassination of Spencer Perceval in 1812 were told, it is unmanly to crave security from the state if you chose to enter public life.

The debate about that will go on for as long as there are historical debates as will the disagreements about Churchill’s post-war premiership. When I posted last month on his resignation, putting forward the opinion that many of Britain’s post-war problems may have been further exacerbated by that government, John Barnes wrote a reply in which he suggested that the comment was less than fair:

“I think you are less than fair to Churchill's second government (should it not be labelled his third?). Signing up to GATT, virtually ending controls, apart alas from exchange control, some measures of denationalisation, all would suggest a degree of economic liberalism that wasn't on offer once Macmillan was firmly in the saddle. And Churchill himself until his stroke was far from ineffective, if not the driving force of the wartime years. Talking with those who served, both politicians and civil servants, in the early '50s reveals a clear consensus that he was non compos in his last six months, but much more dispute about the earlier months in 1954. Might be an excellent issue to do, not on Churchill himself, but on that government. Maggie at times saw it as a precursor, at others part of butskellism. Which view was correct? As you can sense my view is that we have postwar history wrong. We underestimate the socialism of the Attlee Governments, therefore we underrate the importance of the 1951-55 government in rolling back socialism and tend to underplay the part Macmillan played after 1959 in revisiting the corporatist strain in Tory politics.”My own feeling is that not many historians underestimate Attlee’s socialism or Macmillan's corporatism but, possibly, they have not paid enough attention to the few attempts to roll it back made while Churchill was Prime Minister.

Geoffrey Best in his “Churchill: A study in greatness” refers to him as “one-nation Tory” and argues that it was that particular attitude, which made Churchill dislike the fiery class warriors like Aneurin Bevan while having reasonably warm feelings towards many Labour MPs and, especially, his opponent, Clement Attlee.

Others have described Churchill as a Whig or a paternalist Tory (often indistinguishable from the one-nation variety).

By no stretch of the imagination can one call Churchill a small-government Conservative. He may have spoken about freedom but he did not necessarily see it as part of everybody’s every day life. As Best describes, the more ideologically minded anti-socialist Conservatives found Churchill’s post-war leadership very frustrating even before the big stroke almost incapacitated him.

In Opposition he found it difficult to argue with Attlee’s legislation, though he harried the government and encouraged others to do likewise, that being, in his opinion, the role of the Opposition. This is what Best says on p 302 of his book:

“In peace as in war he didn’t like planning for too far ahead; you never knew what unforeseen opportunities and problems might turn up in the meantime. He herefore resisted the enghusiasts’ call for, as he viewed it, a premature declaration of Conservative policy and settled for keeping the party’s commitment to principles and generalities while Labour’s popularity burned itself out.It is not unreasonable to argue that, possibly, there were few alternatives in the immediate post-war years, though many Conservatives saw matters otherwise and were working on ideas that could be put up in opposition to the socialism of Attlee’s government. But things did not change all that much when the Conservatives came back into power.

It was indeed difficult to see what else could profitably have been done. Labour had come into Parliament with 184 more seats than the Conservatives. It set about its ambitious legislative programme without a week’s delay. The first of its seris of nationalisations, that of the Bank of England, was one with which in fact Churchill had a good deal of sympathy; a nationalised bank would not, he thought, have leaned on him to make the wrong decision in 1925. And that was only one of Labour’s measure he had no stomach to oppose.

He had favoured nationalising the railways since the Great War. He would not have been sorry if the coal industry had been nationalised in the troublesome 1920s. He could not find any good arguments against the case for keeping or bringing into public owndership public utilities that were also natural monopolies. …..

Then there was the government’s legislation establishing the National Health Service and comprehensive social insurance. The latter did bring him into action, but only to claim for himself when young, for pre-war Conservative governments and for his wartime coalition most of the credit for what he picked out as the schemes’ more sensible, affordable and discriminating elements.”

This is Best’s analysis on pp 306 -7

“In a political language more familiar now than it was then, Churchill was a ‘wet’. The term already had some currency, and thye general ‘wetness’ of his administration was explicitly lamented by Conservatives of ‘dry’ disposition. But Churchill wanted it that way. It fortified his aspiration to national unity and ran closer to the socio-parliamentary pattern he had always imagined to be the best; no doubt it also flattered his idea of himself as a national leader.And, of course, there was the matter of industrial relations, which settled into their disastrous pattern under Churchill, who, according to Best “had indeed in his old age become an ‘industrial appeaser’.”

….

His government’s policy was therefore was to take over as many of the preceding government’s institutional innovations as it could, and to disturb as little as possible the social and industrial realtions it inherited.”

I shall stop there, having quoted only from Best, who may be said to have approached the subject somewhat from the left and not the somewhat stronger views expressed by Andrew Roberts, a man of the right. The hope, as ever, is that this posting will provoke a discussion, even a debate on a subject that is of great import in conservative history.

While I have been remiss about keeping the blog as up to date as it ought to be (day job and the need to turn my attention to the forthcoming issue of the Journal – hint to contributors - interfering), there have been some very useful responses and comments on previous postings.

As to be expected, John Barnes has made points that are of interest to all of us. I shall pick up his response to the Churchill posting separately, as I should like to see a good discussion on the subject of that great man’s post-war premiership.

However, John has also written interestingly if all too briefly on the subject of Conservative women MPs. As I have said before, the autumn issue of the Journal will focus on women in the conservative movement, going back to the nineteenth century (and earlier, if anyone would wish to contribute on the subject) but certainly covering the enormous contribution women have made to the Conservative Party more recently.

Here are John Barnes’s comments on Conservative women MPs:

“I am struck by the fact that although 13 Conservative women were elected as MPs in 1931, they formed only 3 per cent of the party. Today 17 Conservative women MPs amount to 8 per cent of the party, a stable percentage figure for the last three elections.The second Conservative woman elected to the Commons was Mabel Philipson for Berwick-upon-Tweed (1923-29) and the Duchess of Atholl also entered the Commons in 1923. Obviously the Duchess is as famous as Nancy Astor and, unlike her, achieved office.I couldn't agree more with the point that we need to pay more attention to all these remarkable women. What else is the Conservative History Group for?

But does any one know anything of Mabel Philipson.The thirteen elected in 1931 include such formidable characters as Florence Horsburgh, Irene Ward, Mavis Tate, Thelma Cazalet and the Countess of Iveagh, and of course the Duchess of Atholl and Nancy Astor; but the remainder deserve documentation. They were Ida Copeland, Marjorie Graves, Mary Pickford, Norah Runge, Helen Shaw and Sally Ward.

Sally Ward, whom I knew when contesting Walsall North, lost her Cannock seat in 1935, but went on to have a career in local government, serving on the Staffordshire County Council, and becoming an Alderman. She was not very tall, but a feisty character and an excellent platform speaker. She was a farmer's wife, I believe. Perhaps others can and should document this early generation for the CHG. They deserve to be remembered.”

In the days after local elections, while people are still mulling over what, if anything, the results might portend, it is worth looking at one of Burke’s famous and famously misquoted paragraphs.

How often have we heard that Burke spoke approvingly of “small platoons”? An enquiry on my part as to where that phrase might have come from elicited explanations from two members of the Anglosphere group.

The quotation does not speak of “small platoons” but of “little platoons”, the reference being, presumably, to what was then the smallest military unit. Burke clearly expected his readers to know military terminology even though the army was not precisely highly regarded in eighteenth century Britain.

So here is the full quotation:

“To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed toward a love to our country and to mankind. The interest of that portion of social arrangement is a trust in the hands of allthose who compose it; and as none but bad men would justify it inabuse, none but traitors would barter it away for their own personal advantage.”It comes from one of his greatest works: “Reflections on the Revolution in France” and is as good a summary of the conservative view of society as any has ever been produced. It also reminds one of that wonderful exercise most children get round to doing sooner or later: they write down their names, then their addresses, then the city they live in, then the country, the continent and finally, the world, the universe.

It has been pointed out to me that Nancy Astor was not the first woman MP to be elected, merely the first one to take her seat in the House.

The first one was the Irish Republican and socialist Constance Markiewicz, who was elected in December 1918 but refused to swear the oath of allegiance and, therefore, take her seat.

I realized that as I was writing the entry but decided not to correct it after it had been posted. It is good to know that our readers are alert to mistakes by the bloggers.

In the meantime, here is a quotation from a letter Harold Nicolson wrote to his sons in 1943, which contains a slightly spiteful description of Nancy Astor:

“We had a debate on the reform of the Foreign Service. The main idea is to fuse the Diplomatic with the Consular and Commercial Services. I have been in favour of it for thirty years. But the debate went wrong as usual. The women Members felt that their rights were being trampled on, and staged a full-dress attack on the exclusion of women from the Service.There is more on his exchange of not very attractive witticisms about women and foreign affairs, which proves that despite his much-publicized unconventional marriage to Vita Sackville-West (who was a stauch conservative, by the way) Nicolson had dull and conventional views on the role of women.

Nancy Astor, as the senior woman Member, insisted on voicing their complaint. She has one of those minds that work from association to association, and therefore spreads sideways with extreme rapidity. Further and further did she diverge from the point while Mrs Tate beside her kept on saying, ‘Get back to the point, Nancy. You were talking about the 1934 Committee.’

‘Well, I come from Virginia’, said Lady Astor, ‘and that reminds me, when I was in Washington ….’

I was annoyed by this, as I knew that I was to be called after her. It was like playing squash with a dish of scrambled eggs. Anyhow I made my speech and it went well enough.”

Unfortunately, I cannot lay my hands on my copy of ‘Chips’ Channon’s “Diaries”, where there are other interesting comments about Lady Astor. Perhaps some of our readers could come to my rescue and send in the odd quotation.

Not only the first woman MP to take her seat but the first woman Prime Minister in this country and one who undoubtedly left her mark on the whole world was, as every school child knows (or ought to know), a Conservative.

Not only the first woman MP to take her seat but the first woman Prime Minister in this country and one who undoubtedly left her mark on the whole world was, as every school child knows (or ought to know), a Conservative.

Today is the anniversary of Margaret Thatcher’s victory in 1979. Despite Jim Callaghan’s later self-serving account of that day, few of us outside the circle around the lady knew that this would be a mould-breaking government in more senses than just the obvious: that it was led by a woman.

Our readers must have memories of that day and night.

One of the myths the Conservative History Journal and this blog are anxious to dispel is the one about women’s advance in politics and society being only because of activity on the left of the political spectrum.

One of the myths the Conservative History Journal and this blog are anxious to dispel is the one about women’s advance in politics and society being only because of activity on the left of the political spectrum.

The autumn issue of the Journal will be centred on the subject of women in conservative politics. In the meantime, today is a good day to recall the first woman MP, Nancy Astor, who died on May 2, 1946.

An American, Nancy Langhorne was born in Virginia but moved to England after an unsuccessful first marriage in 1904, marrying Waldorf Astor soon afterwards.

Nancy was for several years, the perfect political wife, if possibly a little more interested in her husband’s and his party’s doings than many. But in 1919 Waldorf Astor became a Viscount on his father’s death and Nancy decided to fight his seat, defeating Isaac Foot, the first of many political “Feet”, father of Michael, John, Hugh and Dingle and grandfather of Paul. (There might be some political “Feet” I have left out.)

Nancy Astor was a strong supporter of the Temperance Movement (a result of that unfortunate first marriage) and her maiden speech was on that subject. Her first private member’s bill raised the age for the purchase of alcoholic drinks to eighteen.

There were other causes: equality in the civil service, suffrage for women at 21 (to make it equal with men) and nursery schools. All in all, she is somebody most women can be grateful to. Furthermore, she was seriously unpopular with Harold Nicolson, who made some very disparaging remarks about her in his diary.

My co-blogger, Iain Dale, has produced a preliminary list of Blair government scandals and is inviting people to write about any one they like. I can’t say I agree with all the ones he lists – some of them are normal behaviour on the part of any government and some, like the money for peerages, is not, in my opinion a scandal.

My co-blogger, Iain Dale, has produced a preliminary list of Blair government scandals and is inviting people to write about any one they like. I can’t say I agree with all the ones he lists – some of them are normal behaviour on the part of any government and some, like the money for peerages, is not, in my opinion a scandal.

Most of them, however, are corkers. Cherie Blair figures in quite a few, though her husband, believed to be the Prime Minister, seems to have distanced himself from her vagaries.

Inevitably, the journalistic cry has gone up: this is as bad as the Major government. With respect to the media, one has to say that this is considerably worse than the Major government. It is true that post ERM (those of us who believe that economic growth is more important than political face-saving prefer to call the day White Wednesday) that hapless government slid into a morass of seeming incompetence and sleaze. Once that image becomes fixed in the public mind, nothing can dislodge it.

The point about the Blair government sleaze is that it is right at the heart of it. The people getting caught out are not junior ministers or backbenchers (often extremely obscure) but senior members of the Cabinet, holders of the great offices of state.

So why is the government not being brought down the way the Major government was, a comment on this blog asked. Well, in the first place, the Major government was not brought down but lost an election after the Prime Minister had gone to the wire with his timing. This is never a good idea: think Sir Alec Douglas Home (who, actually, did much better than expected), James Callaghan and, then, John Major.

The latest spate of scandals will not be judged by the electorate for a couple of years.

There are other differences. The ERM debacle (staying in while the country was plunging into a recession rather than the getting out of it then being bounced out) certainly created the impression of the Tories no longer being able to manage the economy.

By contrast, Gordon Brown may well go down in history as one of the most disastrous Chancellors this country has had for a long time, but his incompetence is being revealed in small doses.

Then there was the appalling spectacle of Maastricht – the long drawn-out agony of that Bill, which was completely unnecessary. After the Danish “no” Major could have said that this was a good opportunity to sit back and take stock. Instead, he went into an unneeded Paving Motion, which he won by three votes and the whole dragged-out spectacle. There has been nothing like it with the Blair government.

Last but not least, there is the question of opposition. By the mid-nineties, somebody has pointed out, the Labour Party seemed ready to take power. As this is a historical not a political discussion, I shall not go beyond that comment.

Links

Followers

Labels

- 1922 Committee (1)

- abolition of slave trade (1)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- academics (2)

- Adam Smith (2)

- advertising (1)

- Agatha Christie (4)

- American history (33)

- ancient history (4)

- Anglo-Boer Wars (1)

- Anglo-Dutch wars (1)

- Anglo-French Entente (1)

- Anglo-Russian Convention (2)

- Anglosphere (19)

- anniversaries (175)

- Anthony Price (1)

- archaelogy (8)

- architecture (8)

- archives (3)

- Argentina (1)

- Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams (1)

- art (14)

- Arthur Ransome (1)

- arts funding (1)

- Attlee (2)

- Australia (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Baroness Park of Monmouth (1)

- battles (11)

- BBC (5)

- Beatrice Hastings (1)

- Bible (3)

- Bill of Rights (1)

- biography (21)

- birthdays (11)

- blogs (10)

- book reviews (8)

- books (78)

- bred and circuses (1)

- British Empire (7)

- British history (1)

- British Library (9)

- British Museum (4)

- buildings (1)

- businesses (1)

- calendars (1)

- Canada (2)

- Canning (1)

- Castlereagh (2)

- cats (1)

- censorship (1)

- Charles Dickens (3)

- Charles I (1)

- Chesterton (1)

- CHG meetings (9)

- children's books (2)

- China (2)

- Chips Channon (4)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (1)

- cities (1)

- City of London (2)

- Civil War (6)

- coalitions (2)

- coffee (1)

- coffee-houses (1)

- Commonwealth (1)

- Communism (15)

- compensations (1)

- Conan Doyle (5)

- conservatism (24)

- Conservative Government (1)

- Conservative historians (4)

- Conservative History Group (10)

- Conservative History Journal (23)

- Conservative Party (25)

- Conservative Party Archives (1)

- Conservative politicians (22)

- Conservative suffragists (5)

- constitution (1)

- cookery (5)

- counterfactualism (1)

- country sports (1)

- cultural propaganda (1)

- culture wars (1)

- Curzon (3)

- Daniel Defoe (2)

- Denmark (1)

- detective fiction (31)

- detectives (19)

- diaries (7)

- dictionaries (1)

- diplomacy (2)

- Disraeli (12)

- documents (1)

- Dorothy L. Sayers (5)

- Dorothy Sayers (5)

- Dostoyevsky (1)

- Duke of Edinburgh (1)

- Duke of Wellington (14)

- East Germany (1)

- Eastern Question (1)

- economic history (1)

- Economist (2)

- economists (2)

- Edmund Burke (7)

- education (3)

- Edward Heath (2)

- elections (5)

- Eliza Acton (1)

- engineering (3)

- English history (56)

- English literature (34)

- enlightenment (3)

- enterprise (1)

- Eric Ambler (1)

- espionage (2)

- European history (4)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- events (22)

- exhibitions (12)

- Falklands (3)

- fascism (1)

- festivals (2)

- films (13)

- food (7)

- foreign policy (3)

- foreign secretaries (2)

- fourth plinth (1)

- France (1)

- Frederick Burnaby (1)

- French history (3)

- French Revolution (1)

- French wars (1)

- funerals (2)

- gardeners (1)

- gardens (3)

- general (17)

- general history (1)

- Geoffrey Howe (2)

- George Orwell (2)

- Georgians (3)

- German history (3)

- Germany (1)

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (1)

- Gibraltar (2)

- Gladstone (2)

- Gordon Riots (1)

- Great Fire of London (1)

- Great Game (4)

- grievances (1)

- Guildhall Library (1)

- Gunpowder Plot (3)

- H. H. Asquith (1)

- Habsbugs (1)

- Hanoverians (1)

- Harold Macmillan (1)

- Hatfield House (1)

- Hayek (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- historians (38)

- historic portraits (6)

- historical dates (10)

- historical fiction (1)

- historiography (5)

- history (3)

- history of science (2)

- history teaching (8)

- History Today (12)

- history writing (1)

- hoaxes (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- House of Commons (10)

- House of Lords (1)

- Human Rights Act (1)

- Hungary (1)

- Ian Gow (1)

- India (2)

- Intelligence (1)

- IRA (2)

- Irish history (1)

- Isabella Beeton (1)

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1)

- Italy (1)

- Jane Austen (1)

- Jill Paton Walsh (1)

- John Buchan (4)

- John Constable (1)

- John Dickson Carr (1)

- John Wycliffe (1)

- Jonathan Swift (1)

- Josephine Tey (1)

- journalists (2)

- journals (2)

- jubilee (1)

- Judaism (1)

- Jules Verne (1)

- Kenneth Minogue (1)

- Korean War (2)

- Labour government (1)

- Labour Party (1)

- Lady Knightley of Fawsley (2)

- Leeds (1)

- legislation (1)

- Leicester (1)

- libel cases (1)

- Liberal-Democrat History Group (1)

- liberalism (2)

- Liberals (1)

- libraries (6)

- literary criticism (2)

- literary magazines (1)

- literature (7)

- local history (2)

- London (14)

- Londonderry family (1)

- Lord Acton (2)

- Lord Alfred Douglas (1)

- Lord Hailsham (1)

- Lord Leighton (1)

- Lord Randolph Churchill (3)

- Lutyens (1)

- magazines (3)

- Magna Carta (7)

- manuscripts (1)

- maps (9)

- Margaret Thatcher (21)

- media (2)

- memoirs (1)

- memorials (3)

- migration (1)

- military careers (1)

- monarchy (12)

- Munich (1)

- Museum of London (1)

- museums (5)

- music (7)

- musicals (1)

- Muslims (1)

- mythology (1)

- Napoleon (3)

- national emblems (1)

- National Portrait Gallery (2)

- nationalism (1)

- naval battles (3)

- Nazi-Soviet Pact (1)

- Nelson Mandela (1)

- Neville Chamberlain (2)

- newsreels (1)

- Norman conquest (1)

- Norman Tebbit (1)

- obituaries (25)

- Oliver Cromwell (1)

- Open House (1)

- operetta (1)

- Oxford (1)

- Palmerston (1)

- Papacy (1)

- Parliament (3)

- Peter the Great (1)

- philosophers (2)

- photography (3)

- poetry (5)

- poets (6)

- Poland (3)

- political thought (8)

- politicians (4)

- popular literature (3)

- portraits (7)

- posters (1)

- President Eisenhower (1)

- prime ministers (27)

- Primrose League (4)

- Princess Lieven (2)

- prizes (3)

- propaganda (8)

- property (3)

- publishing (2)

- Queen Elizabeth II (5)

- Queen Victoria (1)

- quotations (31)

- Regency (2)

- religion (2)

- Richard III (6)

- Robert Peel (1)

- Roman Britain (3)

- Ronald Reagan (4)

- Royal Academy (1)

- royalty (9)

- Rudyard Kipling (1)

- Russia (10)

- Russian history (2)

- Russian literature (1)

- saints (7)

- Salisbury (6)

- Samuel Johnson (1)

- Samuel Pepys (1)

- satire (1)

- scientists (1)

- Scotland (1)

- sensational fiction (1)

- Shakespeare (16)

- shipping (1)

- Sir Alec Douglas-Home (1)

- Sir Charles Napier (1)

- Sir Harold Nicolson (6)

- Sir Laurence Olivier (1)

- Sir Robert Peel (3)

- Sir William Burrell (1)

- Sir Winston Churchill (17)

- social history (2)

- socialism (2)

- Soviet Union (6)

- Spectator (1)

- sport (1)

- spy thrillers (1)

- St George (1)

- St Paul's Cathedral (1)

- Stain (1)

- Stalin (3)

- Stanhope (1)

- statues (4)

- Stuarts (3)

- suffragettes (3)

- Tate Britain (2)

- terrorism (4)

- theatre (4)

- Theresa May (1)

- thirties (2)

- Tibet (1)

- TLS (1)

- Tocqueville (1)

- Tony Benn (1)

- Tories (1)

- trade (1)

- treaties (1)

- Tudors (2)

- Tuesday Night Blogs (1)

- Turkey (3)

- Turner (2)

- TV dramatization (1)

- twentieth century (2)

- UN (1)

- utopianism (1)

- Versailles Treaty (1)

- veterans (2)

- Victorians (13)

- War of Independence (1)

- Wars of the Roses (1)

- Waterloo (5)

- websites (7)

- welfare (1)

- Whigs (4)

- William III (1)

- William Pitt the Younger (4)

- women (11)

- World War I (20)

- World War II (54)

- WWII (1)

- Xenophon (1)

Counters

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(89)

-

▼

May

(12)

- A left-wing historian speaks

- "How it really was"

- Lord Acton and conservative history

- The start of TV electioneering

- Wellington and the mob

- Was Churchill a Conservative?

- Comments on the blog

- Edmund Burke again

- More on Nancy Astor

- Conservative women triumphant

- Death of the first woman MP

- Compare and contrast

-

▼

May

(12)