On Boxing Day Tory Historian fulfilled a long-standing plan and visited Dickens House in Doughty Street. Charles Dickens lived there for only three years but it would appear that all the other houses in London that he lived in have been knocked down. So, one takes what one can get.

On Boxing Day Tory Historian fulfilled a long-standing plan and visited Dickens House in Doughty Street. Charles Dickens lived there for only three years but it would appear that all the other houses in London that he lived in have been knocked down. So, one takes what one can get.

The house is well-arranged and there is a great deal of information about the man, his work, his life and his friends. A rather surprising failing was in the food department. The drawing room was decorated as for an early Victorian Christmas but the display of festive goodies on the table was rather miserable, as were the promised refreshments before a reading of a part of “The Christmas Carol”. This is not a question of greed. Dickens was pre-eminent in his descriptions of food and drink and general jollity. Those refreshments should have included at least a few of the goodies he describes. To have a couple of boxes of Marks and Spencer biscuits and a few cartons of juice with two bottles of rather uninteresting wine did not do the great man justice. Why not mulled wine with a great deal of raisins and orange peel in it together with a really fine Christmas pie? (Is there a possible career for Tory Historian here?)

There was an exhibition called “Ignorance and Want”, referring to the two miserable children who cling to the Ghost of Christmas Present and dealing with Dickens’s fight both in his writing and in action against those evils. The exhibition immediately raised the question of whether Dickens was a radical as he is described by many.

Undoubtedly, he was on the side of the underdog, of the oppressed, of the humiliated, no matter who they were. In “Tale of Two Cities” he makes it clear that the horrors of the revolution are brought about by the behaviour of the French aristocracy or the rather degenerate members of it that he writes about. But, once the tables are turned, the tumbrils are rolling, the tricoteuses are in place there can be no doubt as to whose side the author is on.

Be they underfed and severely flogged children, exploited clerks, girls forced into prostitution or any other group of victims, Dickens was on their side. He wrote about them with real passion and he tried to help through various organizations such as those set up by Angela Burdett-Coutts. But was he a radical?

It was George Orwell in his first-class essay of 1939 entitled simply “Charles Dickens” who first posed this question and noted that Dickens and his novels are loved by all those he attacked: lawyers, civil servants, teachers of all kind, rich and poor alike. The reason for that, Orwell posited, is that Dickens had not interest in either changing or subverting society.

A true representative of the English urban middle class, according to Orwell, Dickens had no interest in serving society.

Parliament is simply Lord Coodle and Sir Thomas Doodle, the Empire is simply Major Bagstock and his Indian servant, the Army is simply Colonel Chowser and Doctor Slammer, the public services are simply Bumble and the Circumlocution Office – and so on and so forth. What he does not see, or only intermittently sees, is that Coodle and Doodle and all other corpses left from the eighteenth century are performing a function which neither Pickwick nor Boffin would ever bother about.Similarly, with education, a topic very close to Dickens’s heart. As Orwell points out, the schools Dickens approves of, such as that of Dr Strong’s are no different from Mr Creakle’s except that the former is run well by a man of noble feelings and attitudes who genuinely loves learning. Why does Dickens not offer some ideas of educational reform, asks Orwell. Why cannot he see that it is the whole system of private property and private enterprise that is wrong?

The obvious answer to that is provided by the essayist himself: Dickens was not a political animal and did not really believe that changing structures was more important than changing human souls.

Looking back on the twentieth century one cannot help agreeing with Dickens rather than with Orwell, except that the latter also half-agreed with the former. It’s just that he could never completely discard his socialist assumptions. Now that we have an almost complete state control of education, classics have been discarded and teaching has become modern, relevant and child centred, Ignorance is more strongly ensconced than ever before.

The people in countries where private property was abolished led and still lead a more wretched existence than those where private property remained the norm. It is, after all, private individuals like Shaftesbury who fought against injustice and oppression, such as the overworking of young children in homes and factories.

Dickens was nearer the mark about trade unions: they did turn out to be little more than cartels and not really the great hope of the working man.

For all of that, Orwell has a point about Dickens. He may be on the side of the oppressed but he does not particularly intend to have the oppressed take their lives into their own hands. The famous episode of David Copperfield working in the glass washing factory, based on Dickens’s own experience in the blacking factory, is a case in point. David is miserable and the author is entirely on his side. But part of his misery is that he has to associate with the low boys of the factory. David escapes and we cannot help feeling that it is right and proper that he should not work ten hours a day for a miserable pittance in appalling conditions. There is no indication that Dickens thinks that the other boys should not work ten hours a day for a miserable pittance in appalling conditions. Perhaps, if some kindly gentleman or lady rescues them and restores them to their rightful middle class position that can be acknowledged.

Dickens has little sympathy with men who try to better themselves. Such characters range from the creepy and oleaginous Uriah Heep to the tragic Bradley Headstone, driven by his demons to attempt murder and commit suicide. Young women may marry above their station, it being an accepted way of advancing, but young and not so young men must not look up in their search for a partner. (Though Florence Dombey marries somewhat below her to a young naval officer, possibly the only time servicemen appear in a positive light.)

There is a great deal more one can say about Dickens, of course, but also about Orwell, who strangely enough finds himself in great sympathy with the man who thought that it was personal change and personal improvement that mattered. Some of Orwell’s comments are entirely correct – it is odd the way none of the heroes ever seem to want to do a job of work in Dickens’s novels unless they are driven to it by some hideous misfortune – sometimes he is completely wrong as when he suggests that Dickens “is scarcely intelligible outside the English-speaking culture”. But he ends with a rousing defence of Dickens and his particular brand of conservative radicalism:

When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. … What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens’s photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.Something similar could be said about Orwell, despite his determined attempts to cling to socialist ideology.

The Hundred Years’ War notoriously lasted 115 years. Either they could not count or they did not know precisely when it started and when it ended. Or, possibly, historians prefer snappy names and titles. Well, anyway, I used to think it was 115 years, but Wikipedia says it was 116, from 1337 to 1453.

The Hundred Years’ War notoriously lasted 115 years. Either they could not count or they did not know precisely when it started and when it ended. Or, possibly, historians prefer snappy names and titles. Well, anyway, I used to think it was 115 years, but Wikipedia says it was 116, from 1337 to 1453.

The beginning is slightly muddled, with French ships attacking coastal settlements, arguments over the Gascon fiefdom and Edward III helpfully telling the French that he was, in fact, their rightful king.

The ending is probably the last battle, that of Castillon when Talbot (you cannot get much more Shakesperian) was defeated while trying to retake Gascony. Then again, one could argue that the real last battle was that of Calais in 1558. (Whenever people tell me that countries, such as Serbia, have a right to something or other because they were there in the fourteenth century, I suggest taking large parts back to be ruled by the English. Or, at least, an alliance with Burgundy, which had been incorporated forcibly into France round about the time the English lost Calais. Strangely, I get no response.)

While not every year of those 115 or 116 were taken up with fighting a good many were and a very muddled business it was, too, with various smaller states, changing sides as they saw fit, rebellions breaking out within them and peace treaties being signed and broken.

Who knows all the official combatants? On one side there were England, Burgundy, Brittany, Portugal, Navarre, Flanders, Hainault, Aquitaine and Luxembourg; on the other, France, Castile, Scotland, Genoa, Majorca, Bohemia and Aragon. But the lists changed from time to time. It is reasonably clear that one aim of the war was to subdue various duchies and smaller states that the King of France wanted to control.

Enough of that. Let us move on to other wars. The Thirty Years’ War, amazingly enough, lasted just that, starting with the famous second (and unsuccessful) defenestration in Prague in May 1618. (Oh, all right, since you ask, the first one was the killing of seven council members by angry Hussites by throwing them out of the window on to the spears of the armed congregation. (Armed congregation? How different from the everyday life of our own Church of England.)

In the second one, the Protestant Assembly threw out two Imperial governors who had tried to impose their own Roman Catholic religion. The two landed on a pile of manure and left unharmed, though rather smelly.

The final defenestration took place 330 years later, in March 1948. As the Communists took over, the non-Communist Foreign Minister, Jan Masaryk was found under his bathroom window. Yes, I suppose, it might have been suicide. Or he might have been suicided on the orders of Klement Gottwald, the Communist leader.

The ending of the Thirty Years’ War (returning to our muttons) was also clearly defined with the Peace of Westphalia, the two treaties, that of Münster and Osnabrück, signed in the spring of 1648. Confusingly, these also ended the Eighty Years’ War, that of Dutch independence from Spain. (With me, so far?)

The Peace of Westphalia is quite often referred to as the Treaty of Westphalia and is one of the most misunderstood and misquoted documents in modern history. In fact, Tory Historian intends to do a long blog on the subject just as soon as ….

The Thirty Years’ War may have had a definite beginning and ending but it was a muddled affair, with various German states fighting here and there, not to mention Bohemia (part of the Holy Roman Empire), Sweden, France (which did rather well out of it, what with getting Alsace-Lorraine and Metz), Denmark, Spain and the Dutch.

When one gets to the eighteenth century, it can seem as if there was nothing but toing and froing, what with the War of Habsburg Succession and the Seven Years’ War with the diplomatic revolution between them. Still, they all ended with a peace treaty and a more or less accepted settlement.

The continuing French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars remain a headache for all. Again, we know when they ended, though before that there were many breaks, peace treaties that did not hold and countries changing sides either voluntarily or not. That, too, is a subject for another blog or, perhaps, several.

Let us move on, rather rapidly, to the twentieth century. How many wars did it have? My own supervisor at Oxford, A. J. P. Taylor, said a long time ago that the two World Wars were in reality one war that lasted from 1914 to 1945. The two main antagonists remained the same but others changed, empires broke up, new states were created, and various rebellions and changes in political systems rearranged the picture.

Margaret Macmillan in “The Peacemakers” seems reasonably certain that most of what was done in 1945 about Germany should have been done in 1919, though she does acknowledge that the presence of a much stronger United States and Soviet Union changed the situation somewhat.

Much of what the peace negotiations of 1919 wanted to achieve was not to be seen until well after 1945.

Is that the end of the story, though? We know when the great war of the twentieth century started – those shots in July 1914 in Sarajevo. But, just as the Hundred Years’ War started and ended in Gascony, so the twentieth century war started and ended in Sarajevo with the collapse of the Yugoslav state, created with some trouble in 1919 and never at peace with itself.

The end of that process that started with Gavrilo Princip’s shots has not yet arrived. The post-1945 political structure started to unravel in 1991 as the Soviet Union disintegrated but has not stopped doing so.

The after effects of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire have recently become stronger in the Middle East. Iraq was created in the 1920s, as were most of the modern states in the area.

Started in 1914 and ended when? Are we living through another hundred years’ war?

Few British Prime Ministers evoke such passionate feelings on both sides than Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton.

Few British Prime Ministers evoke such passionate feelings on both sides than Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton.

To some he is the hero of one-nation conservatism, the man who had seen the need to take Britain into the Common Market (now the European Union), the Tory toff who, not entirely illogically, believed in the state control of almost every part of British economy, thus, slightly less logically, defeating socialism.

To others, he is part of the British problem. His refusal to understand that "manging socialism better than Labour can" contributed to the crisis that was only partially solved by Thatcher's reforms (which he rather grandly criticized in his famous comments about the family silver).

There is no getting away from the fact that the man was a fascinating character, devious and secretive, fond of his buffoonish pretence and an excellent speaker. Tory Historian can recall a speech he made at the opening of the new History Department in Oxford, his rather doddery diction suddently acquiring strength and crispness when he came to criticizing people he disliked.

The Tory Reform Group has unearthed a recording of Lord Stockton making a speech at the group's 10th anniversary dinner in 1985. Our readers might well enjoy listening to it.

Just about two weeks ago I asked a mutual acquaintance about Frank Johnson's health and was told that he was as well as can be expected, though counting each week as a blessing. Those blessings have come to an end. This morning, Frank Johnson died at the age of 63 this morning. The words "after an illness bravely borne" have become a bit of a cliche but in this case they are absolutely accurate.

Just about two weeks ago I asked a mutual acquaintance about Frank Johnson's health and was told that he was as well as can be expected, though counting each week as a blessing. Those blessings have come to an end. This morning, Frank Johnson died at the age of 63 this morning. The words "after an illness bravely borne" have become a bit of a cliche but in this case they are absolutely accurate.

Frank's biography is well-known: the son of an East End pastry cook, he left school with one O-level (reportedly in woodwork) and started his spectacular career as the tea boy on the Sunday Express. After a stint on the Walthamstow Guardian, Liverpool Post and The Sun, he was hired by that prince of all editors, Colin Welch, to be a reporter in the House of Commons on the Daily Telegraph.

He and John O'Sullivan shared the sketch writing, a witty revival of much earlier parliamentary reporting. They also promoted Margaret Thatcher's free-market policies in the late seventies in the teeth of establishment opinion (though they were supported by Colin Welch).

An auto-didact, immensely knowledgeable about history, literature, classical music and other cultural matters, Frank Johnson was a natural conservative but one who is unlikely to be appreciated (despite the undoubted crocodile tears that will flow) by the present Tory-Toff leadership.

In between other tasks Tory Historian has been ploughing on with Margaret MacMillan’s “Peacemakers”. Actually, that is the wrong expression as the book is very interesting and extremely well written. Even the fact that Dr MacMillan clearly has a special fondness for those two rogues, Lloyd George and Clemenceau, does not detract from the interest in this detailed and vivaciously told book.

In between other tasks Tory Historian has been ploughing on with Margaret MacMillan’s “Peacemakers”. Actually, that is the wrong expression as the book is very interesting and extremely well written. Even the fact that Dr MacMillan clearly has a special fondness for those two rogues, Lloyd George and Clemenceau, does not detract from the interest in this detailed and vivaciously told book.

As the story unfolds the reader can follow the creation and growth of the many problems the world is still trying to grapple with.

It will be interesting to see whether Margaret MacMillan will produce the costs of the Paris Conference. The participants of the Great War had come out significantly poorer than they had gone in. France, in particular, had suffered enormously, both in economic and human terms, as Clemenceau never ceased to remind others of the Conference. Yet it managed to lay on an astonishingly lavish conference and many of the participants spent much of their remaining income on large and well-equipped delegations.

Some discussions, though, do not change:

The Supreme Council managed to choose a secretary, a junior French diplomat who was rumoured to be Clemenceau’s illegitimate son. (The extraordinarily efficient [Sir Maurice] Hankey, the deputy secretary, soon took over most of the work.) After much wrangling it decided on French and English as the official languages for documents. The French argued for their own language alone, ostensibly on the grounds that it was more precise and at the same time capable of greater nuance than English, in reality because they did not want to admit France was slipping down the rankings of world powers.But the row has gone on ever since.

French, they said, had been the language of international communication and diplomacy for centuries. The British and Americans pointed out that English was increasingly supplanting it.

Lloyd George said that he would always regret that he did not know French better (he scarcely knew it at all), but it seemed absurd that English, spoken by over 170 million people, should not have equal status with French.

The Italians said, in that case, why not Italian as well. ‘Otherwise,’ said the foreign minister, Sonnino, ‘it would look as if Italy was being treated as an inferior by being excluded’.

In that case, said Lloyd George, why not Japanese as well? The Japanese delegates, who tended to have trouble following the debates whether they were in French or English, remained silent. Clemenceau backed down, to the consternation of many of his own officials.

Today is the 65th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbour and here is a picture of what the place looked like immediately after it.

Today is the 65th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbour and here is a picture of what the place looked like immediately after it.

Rather than discussing the attack I should like to pose a couple of questions. After the Japanese attack on the United States, Germany declared war on that country as well. As it happens, Hitler could have gone the other way. He disliked America and all it stood for but, given his views on race, he could not have been all that fond of the Japanese either. What would have happened if he had allied himself with the United States and declared war on Japan? Or stayed out of the conflict in the Pacific?

It should have been yesterday but a twisted ankle kept Tory Historian from the computer. November 28, 1990 – most of us can remember the day Margaret Thatcher formally resigned as Prime Minister and made a last, tearful statement from Downing Street:

It should have been yesterday but a twisted ankle kept Tory Historian from the computer. November 28, 1990 – most of us can remember the day Margaret Thatcher formally resigned as Prime Minister and made a last, tearful statement from Downing Street:

We're leaving Downing Street for the last time after eleven-and-a-half wonderful years and we're happy to leave the UK in a very much better state than when we came here.How many Prime Ministers can honestly say that?

A thirty-minute radio play with that title by Agatha Christie was broadcast in May 1947 on Queen Mary’s 80th birthday, as a present for her (the royal family has had a number of Christie fans among its members).

A thirty-minute radio play with that title by Agatha Christie was broadcast in May 1947 on Queen Mary’s 80th birthday, as a present for her (the royal family has had a number of Christie fans among its members).

Later Christie expanded the play into a longer one (she often developed themes first explored in short stories to create novels), called “The Mousetrap”. And who has not heard of it?

The play opened at the Ambassadors Theatre on November 25, 1952 and has been running ever since, though it transferred to St Martin’s Theatre some years ago. There have been over 21,000 performances and more than 300 actors have played in it.

The original stars were Richard Attenborough and Sheila Sim. Any other information you want? There is a website devoted to the play, which will tell you everything you want to know. Well, almost everything. The identity of the murderer remains a closely guarded secret.

For once, The Scotsman has produced a fascinating article.

For once, The Scotsman has produced a fascinating article.

It seems that the diaries of James Fraser, an Episcopalian Minister, who set off in 1657 from Inverness, journeyed to Aberdeen, down the east coast of Scotland to Edinburgh, then to England, where he described the country under Cromwell's rule that he definitely disapproved of, and to a number of Continental countries.

During his expedition, Fraser witnessed the early days of Cromwell's London, was suspected of being a Protestant spy in a Catholic college and even took a job with the Swiss Guard in Rome and guarded the Queen of Sweden's residence.He was fascinated by what he saw in England and by the English, whom he describes as great meat eaters. His view of the body politic was pessimistic:

He was keen to learn about other religions and wanted to see England and Rome: "ones the seat of the Roman Empire, & who suddenly invaded the world and fixt it selfe such firm foundations as [none] other ever did. Also held to be the fountain of all Science, policy and arts civil and Ecclesiastick. Hopeing to find some sparks of these Cinders not yet put out among the modern Romains."

But there was never more treason in England and about London than now; though not against a King, butt against a parlement, a Commonwalth, a Cromuell. Some one or other every day impeacht for high treason against the State (so tearmed) Lords, souldioures, Churchmen, Phisitians, some hangd, others have their heads cut off, some shot to death, which is the Military execution; for after King Charles his death, the Scaffold runs still wt bloud.Equally interesting comments are quoted from his description of other countries.

Fraser was not well off and could not travel in a leisurely fashion affected by the sprigs of nobility. Nor could he, one presumes, live on credit, also done by the self-same sprigs. He travelled cheaply, got jobs, rather the way young people do now and, no doubt, took advantage of hospitality extended by various religious establishments.

The diary is due to be published and Tory Historian, for one, is waiting with bated breath.

The death of Milton Friedman yesterday at the age of 94 has prompted a great deal of reminiscing. While the Nobel laureate economist was not precisely a conservative with either a small or a big c, he was the progenitor of many economic and political ideas that made modern conservatism exciting and successful for a long time.

The death of Milton Friedman yesterday at the age of 94 has prompted a great deal of reminiscing. While the Nobel laureate economist was not precisely a conservative with either a small or a big c, he was the progenitor of many economic and political ideas that made modern conservatism exciting and successful for a long time.

So, here are a few quotes that Tory Historian would like to share with the readers (who might want to come up with quotes and stories of their own):

I am favor of cutting taxes under any circumstances and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it's possible.And for anyone who has not yet done so, read "Free to choose" by Rose and Milton Friedman. Easy to read, easy to understand, easy to convert to.

Hell hath no fury like a bureaucrat scorned.

Many people want the government to protect the consumer. A much more urgent problem is to protect the consumer from the government.

Nobody spends somebody else's money as carefully as he spends his own. Nobody uses somebody else's resources as carefully as he uses his own. So if you want efficiency and effectiveness, if you want knowledge to be properly utilized, you have to do it through the means of private property.

The Great Depression, like most other periods of severe unemployment, was produced by government mismanagement rather than by any inherent instability of the private economy.

There's no such thing as a free lunch.

Today is the Prince of Wales’s birthday but that seems to fade into insignificance when one notes that November 14, 1922 was the day of the first broadcast by the newly formed British Broadcasting Company from station 2LO, located at Marconi House, London.

Today is the Prince of Wales’s birthday but that seems to fade into insignificance when one notes that November 14, 1922 was the day of the first broadcast by the newly formed British Broadcasting Company from station 2LO, located at Marconi House, London.

Of course the real problems came in 1927 when the British Broadcasting Corporation was formed under Lord Reith, a Royal Charter was granted and the possibilities of independent broadcasting were scotched for many years to come.

Indeed, that Royal Charter and the licence (in effect a poll tax) are still with us and still distorting broadcasting in this country, despite the various technological developments since 1922.

In Flanders fields the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

The First World War produced more poems in the English language than possibly any other. This particular one was written by a Canadian, Dr John McCrae in early May 1915, during the second battle of Ypres. It was first published, anonymously, in Punch in December of that year, though the authorship was soon established.

Dr McCrae stayed in France until January 1918. He died of pneumonia, compounded by exhaustion and depression on January 28. He was 45 years old.

Some years ago one of Tory Historian’s clever-dick journalist friends put forward the suggestion that Remembrance Day should be moved from November 11 (and, presumably, Remembrance Sunday from the nearest Sunday) because that was too closely linked in people’s minds with the First World War. This was before Gordon Brown in a fit of leadership fever suggested having a British Veterans’ Day.

To all of these suggestions Tory Historian can reply with the well-known political adage: “if it ain’t broke, don’t mend it”. The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month is easy to remember and the inherited memory of that war is hard to erase (or change despite its severe inaccuracies) precisely because of the poems.

While the image created by the poets was potent the analysis that has grown out of it is not entirely accurate. The image serves us well for remembrance of the dead of that and many other wars.

They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old,

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn,

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

With Remembrance Day approaching fast, Tory Historian has at last managed to start reading Margaret Macmillan’s multiple award winning “Peacemakers”, an account of the negotiations, intrigues and agreements that resulted in the Versailles Treaty as well as the various other satellite treaties at the end of World War I.

With Remembrance Day approaching fast, Tory Historian has at last managed to start reading Margaret Macmillan’s multiple award winning “Peacemakers”, an account of the negotiations, intrigues and agreements that resulted in the Versailles Treaty as well as the various other satellite treaties at the end of World War I.

The twentieth century is a somewhat odd one. Various historians, conservative and others, have called it “the short century” as its reality did not begin till 1914. One must recall that, unlike the twenty-first century, which was greeted with a great deal of gloom and depression, the twentieth was seen almost everywhere (Russia was probably a notable exception) as one that heralded in a new and better, more peaceful, more advanced future.

Those were days when the word “modern” meant something and the something was, by and large, positive. A century later it is a word that is used with deep gloom by most people except politicians who produce it in order to impose something deeply unpopular and, usually, rather oppressive on the population.

The Great War is generally seen as the beginning of the many horrors that the succeeding twentieth century consisted of. And all for what? After tens of millions of deaths, hundreds of millions wounded, tortured, imprisoned, deprived of their homes and property; after whole societies and cultures destroyed, at the end of the century much of what had seemed to have been wrapped up in the first twenty years reappeared in the news.

Once again the media resounds to names like Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kabul and Heart, Baghdad and Basra. Almost a hundred years after the signing of the Versailles Treaty, whose terms are often described as inevitably leading to World War II, we are still grappling with the problems either created or set loose by those negotiations in Paris so ably and wittily described by Dr Macmillan.

Let us, however, look at the beginning of it all, the great hopes of a new world that was going to be created by the great and wise in Paris out of the horrors of the war that had recently ended.

For four years the most advanced nations in the world had poured out their men, their wealth, the fruits of their industry, science and technology, on a war that may have started by accident but was impossible to stop because the two sides were too evenly balanced. It was only in the summer of 1918, as Germany’s allies faltered and as the American troops poured in, that the Allies finally gained the upper hand. The war ended on 11 November. Everywhere people hoped wearily that whatever happened next would not be as bad as what had just finished.Little did they know and, perhaps, just as well. It is always good to have a little period of hope, though it was already disappearing in some parts of Europe. As it happens, yesterday was the anniversary of the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd, a coup which destroyed any hopes of Russia developing along some kind of democratic path; a coup that created the most monstrous of history’s many monstrous systems; a coup that probably completed the destruction of European power.

Margaret Macmillan continues:

Four years of war shook forever the supreme self-confidence that had carried Europe to world dominance. After the western front Europeans could no longer talk of a civilizing mission to the world. The war toppled governments, humbled the mighty and upturned whole societies. In Russia the revolutions of 1917 replaced tsarism, with what no one yet knew. At the end of the war Austria-Hungary vanished, leaving a great hole at the centre of Europe. The Ottoman Empire, with its vast holdings in the Middle East and its bit of Europe was almost done. Imperial Germany was now a republic. Old nations – Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia – came out of history to live again and new nations – Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia – struggled to be born.

All this required a great deal of management, which was impossible. The conflicting claims, the desire to go forward with some kind of liberal structures, the need not to destroy the defeated countries (overlooked at some cost to themselves eventually) by some of the victors, the hope for peace that would be guaranteed by international bodies and, above all, the reality on the ground of a messy, disintegrating political world, produced peace treaties that were flawed at best and botched at worst.

All this required a great deal of management, which was impossible. The conflicting claims, the desire to go forward with some kind of liberal structures, the need not to destroy the defeated countries (overlooked at some cost to themselves eventually) by some of the victors, the hope for peace that would be guaranteed by international bodies and, above all, the reality on the ground of a messy, disintegrating political world, produced peace treaties that were flawed at best and botched at worst.There will be more postings about the book and its subject. Responses and discussions will, we hope, be forthcoming.

Tory Historian was brought up to believe that dates are the backbone of history. This is not a particularly popular view among school teachers and examiners nowadays, which may account for the number of people who find history boring. Boring? How can one find it boring? It’s about people and what they did and why.

Tory Historian was also, as mentioned in at least one previous posting, brought up by a historian father whose memory for historical dates was phenomenal and who related any date and any set of figures to a well-known historical event. Some things run in the family.

So, what have we for today? What happened on this day in history and how was the world affected by any of them?

1517, for all those who did Tudors’n’Stuarts for history A level was the year in which Martin Luther posted his 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg and that was on October 31. The outcome is of undoubted importance as the beginning of the split in the Western Christian Church and growth of Protestantism.

Do we care about Houdini dying on this day in 1926 as a result of being punched in the stomach before he could prepare his muscles? Perhaps not, except maybe to point out that the man born, as Erik Weisz in Budapest, was another Hungarian who made his mark on the world. Well, no, that is not all that important.

1961, October 31 saw the removal of Stalin’s body from the Mausoleum after two denunciations by the then General Secretary of the CPSU, Nikita Khrushchev at the Twentieth Congress in 1956 and the Twenty-Second Congress in 1961, though it is possible that the body was beginning to smell a bit and, therefore, had to be burnt with the ashes placed into the Kremlin wall.

1776, October 31, saw King George III addressing the British Parliament (well, the House of Lords, to be precise) for the first time since the American Declaration of Independence. He announced the victory over George Washington’s forces at the Battle of Long Island, after which the War of Independence could have gone differently with, possibly, numerous Patriot officers executed as traitors. However, the defeated army was dealt with leniently and further negotiations were attempted. But the King was right: the campaign was going to be long and difficult and, as nobody fully realized at the time, victorious for the Patriots. A good day for the Anglosphere? Presumably, the Loyalists did not think anything was good about the War of Independence or its outcome.

On this day in 1956 the British and French troops landed in the Suez canal zone, the Israelis having already swept through the Sinai. Suez deserves a separate posting and an article in the next issue of the Conservative History Journal, being a turning point in the development of the Western alliance after World War II.

In 1984 on this day, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh guards in revenge for the attack on the Golden Temple in Amritsar in 1984.

However, the most exciting event took place on October 31, 1892 with the publication of “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” as a volume. The first novella, “A Study in Scarlet”, had been published in Beeton’s Christmas Annual of 1887 and the individual stories of the collection had been coming out in Strand Magazine since 1891. But this was the first collection. A great day for all of us.

You can tell a good deal about a country by its sausages. England is quite unusual in that all of them are raw (though there are now attempts by various butchers to make salami and other suchlike delicacies). Tory Historian has been reminded on various occasions of Otto von Bismarck’s saying:

You can tell a good deal about a country by its sausages. England is quite unusual in that all of them are raw (though there are now attempts by various butchers to make salami and other suchlike delicacies). Tory Historian has been reminded on various occasions of Otto von Bismarck’s saying:

People who enjoy eating sausage and obeying the law should not watch either being made.That’s as may be. Tory Historian recalls a very pleasant visit as a child to a salami factory in one of the two countries that make the best. (Guesses are accepted in the comments section.)

This week is apparently British Sausage Week, which is not a theme, many of our readers will say, for the Conservative History Blog. However, at the end of a reasonably interesting article in the Daily Telegraph business section there is the following information:

Despite all this, not all is well in the sausage world, with the frozen variety seeing sales slump by 9.6pc last year. At least, it's not as much of a crisis as the one that hit the sausage world 1,200 years ago when Byzantine Emperor Leo V declared the sausage-makers would be "severely scourged, smoothly shaved and banished from our realm forever".Leo V? One of the famous iconoclastic Emperors? Were the sausage makers in cahoots with the iconodulists, whose policies were associated according to Wikipedia, with Byzantine defeats by the Bulgarians and the Arabs? An interesting idea.

It's not clear what sausage-sellers had done to squeeze the emperor's casing. Still, Leo ended up being assassinated and therein lie some lessons for us all. It's clearly not worth getting in the way of this sausage machine.

Reading on, however, it would appear that there has been a confusion between Leo V (the Armenian), who reigned from 813 to 820 and Leo VI (the Wise), who reigned from 866 to 912. Edward Gibbon thought that the moniker could be explained by the fact that he

was less ignorant than the greater part of his contemporaries in church and state, that his education had been directed by the learned Photios, and that several books of profane and ecclesiastical science were composed by the pen, or in the name, of the imperial philosopher.

Be that as it may, Leo VI seems to have led as colourful a life as his predecessor and successors, many of whom were assassinated (Leo V, apparently, as he was praying in the Hagia Sophia). But there is one thing Leo VI did do that marks him out from the long list of Byzantine emperors: he outlawed the production of blood sausages after cases of food poisoning.

Be that as it may, Leo VI seems to have led as colourful a life as his predecessor and successors, many of whom were assassinated (Leo V, apparently, as he was praying in the Hagia Sophia). But there is one thing Leo VI did do that marks him out from the long list of Byzantine emperors: he outlawed the production of blood sausages after cases of food poisoning.This is clearly different from the banning of the eating of sausages, introduced by Constantine and supported by the early Christian Church, as the act was connected with the pagan Roman festival of Lupercal. Leo VI was clearly the predecessor of the modern environmental and health officers or, even, the Food Standards Agency.

This autumn sees a number of important anniversaries; the fiftieth anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution and of the Suez crisis, as well as of the Melbourne Olympics with its notorious water polo match.

This autumn sees a number of important anniversaries; the fiftieth anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution and of the Suez crisis, as well as of the Melbourne Olympics with its notorious water polo match.

Then there are the less important non-round anniversaries. October 23, 1942 saw the start of the Battle of El-Alamein and October 24, 1945 witnessed of the beginning of that glorious institution, the United Nations.

In 1945, representatives of 50 countries met in San Francisco at the United Nations Conference on International Organization to draw up the United Nations Charter. Those delegates deliberated on the basis of proposals worked out by the representatives of China, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States at Dumbarton Oaks, United States in August-October 1944. The Charter was signed on 26 June 1945 by the representatives of the 50 countries. Poland, which was not represented at the Conference, signed it later and became one of the original 51 Member States.By the time Poland became a founding member it had become clear that the country was not going to have an independent existence. In the Soviet Union they were busy imprisoning all those who were returning or were being returned from POW camps and those who had been displaced persons.

The United Nations officially came into existence on 24 October 1945, when the Charter had been ratified by China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States and by a majority of other signatories. United Nations Day is celebrated on 24 October each year.

Many of the all-conquering Red Army found its way to the camps, because they belonged to the wrong national group (Chechens, Ingushi and Tatars, for example) or because they talked too much about conditions in Europe even after a totally destructive war as opposed to conditions in the motherland.

France was becoming embroiled in two ferocious and inglorious colonial wars: in Vietnam and Algeria.

And so on, and so on. But the Charter was signed and the UN became a body to be spoken off with awe and respect despite its ever-growing shortcomings.

Of course, it was even worse in the fifties and sixties when only very few people pointed out the chaos that ensued whenever the UN became involved (with the solitary exception of the Korean war, which could go ahead because the Soviets were huffing and puffing and wouldn’t occupy their chair or veto the resolution) and even fewer spoke of the lack of consistency between the Charter and the behaviour of the founding members.

In preparation for one of the 50th anniversaries – of the Suez crisis – Tory Historian have been reading the newly published pamphlet by Sir Philip Goodhart, who was actually there, reporting for the Sunday Times. “A Stab in the Front” is distributed by the Conservative History Group and is well worth a read.

There are depressingly familiar aspects to the crisis as described by Sir Philip from the day of Nasser’s nationalization of the canal to the outbreak of hostilities and their ignominious end (though the Israelis might not think so after the successful Sinai campaign).

The most depressing part of it is the alacrity with which the Labour Party abandoned all intention to think clearly about the issues involved and started repeating the mantra of the United Nations. We must refer the matter to the UN. We must do as the UN says after an undoubtedly prolonged and agonizing discussion, sabotaged at all levels by the Soviet Union, by that time President Nasser’s main patron.

Curiously enough, it was Nye Bevan who opposed all this nonsense, asserting that Nasser was a thug and that

the only slogan sillier than “My country right or wrong” is the “United Nations right or wrong.For once, Tory Historian has to admit that Nye Bevan got it just right.

Tory Historian thought that readers of this blog would like to see this rather jolly picture of the three great men, who between them did more than anyone to create the Thatcherite revolution and the revival of the Conservative Party’s fortunes (well, so it looked at the time).

Tory Historian thought that readers of this blog would like to see this rather jolly picture of the three great men, who between them did more than anyone to create the Thatcherite revolution and the revival of the Conservative Party’s fortunes (well, so it looked at the time).

The last of them, Lord Harris of High Cross (the one with the moustache) died yesterday of a heart attack. His end was swift and painless and he was active almost to the last minute, having been sighted in the House of Lords just a day or so before it.

The last couple of times Tory Historian sighted the great man was at meetings of the Bruges Group. One was addressed by Jim Bennett, author of “The Anglosphere Challenge” and founder of the Anglosphere Institute and the other one by that stalwart Conservative historian and Anglspherist, Andrew Roberts on the subject of his new book: “The History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900”.

On both those recent occasions Ralph was greatly excited by the plethora of new ideas he was being presented with and by the notion that political discourse, of which he sometimes despaired, was moving into completely new and fascinating directions.

He was the first in the queue to buy Andrew Roberts’s book (sending Tory Historian off to get him a glass of wine).

On both occasions one could not help wishing for an old age that continues to be so full of intellectual vim and curiosity. And so it has proved for him. Way to go, Ralph.

What will replace the old guard?

Time to look at some other countries, says Tory Historian, guided as ever by recent reading. The historian in question is the late great Professor Leonard Schapiro, whose analysis of Russia and the Soviet Union have been equalled by few.

Professor Schapiro’s oft reiterated argument was that free, just and democratic societies could exist only if there was a full understanding and acceptance of the rule of law within them. In particular, he was an admirer of the English common law, that had spread across the Anglospheric countries of the world (though, to be fair, he did not use that expression) and of the adversarial form of political and legal institutions in this country.

Born in pre-revolutionary Russia, Schapiro trained as a lawyer in England, served in Intelligence during the Second World War, later teaching government and politics at the London School of Economics, specializing often in Russian and Soviet history, politics and literature. He also translated Turgenev’s “Spring Torrents” and published a highly regarded biography of that writer. (Actually, now that I think of it, the man’s career is rather depressing for the rest of us who could not possibly keep up with that.)

Anyway, back to that reading matter. I have been reading and, in some cases, re-reading, Schapiro’s essays on various subjects and was greatly struck by his comments on the Nuremberg Trial in the first of those: “My Fifty Years of Social Science” first published in 1980.

In so far as there is any kind of an idea of what that nebulous term, international law, means, (apart from the obvious matters of various agreements on behaviour at sea, in the air etc etc), it has grown out of that first international trial for crimes against humanity and the creation of the United Nations within a couple of years of it. Professor Schapiro was an opponent of both initiatives:

So far as I was concerned the most powerful single factor that rid me of any illusion that the Soviet Union might have changed after the war was the Nuremberg trial, and the way in which it entered into the fabric of international relations. Nuremberg was both an appalling travesty of international law, a craven acquiescence in and tacit acceptance by the Western powers of the principle that the grim record of the Soviet Union in its treatment of its population was beyond criticism.Opponents of the Tribunal and the Trial have also pointed out that the leading Soviet judge was Major-General Nikitchenko who had been a judge at some of the show trials of the thirties and the main Soviet prosecutor was General Rudenko, an active participant in the Katyn massacre of Polish officers, one of the charges he tried to indict Germany for at Nuremberg. (The main prosecutor at the Soviet show trials, whose hysterical outbursts defined that whole ghastly episode in Soviet history, was Andrei Vyshinsky, who later became the Soviet representative at the United Nations.)

International law was traduced by the introduction of the new principle of law which certainly did not exist at the time the acts were committed that waging an aggressive war is an international crime. As regards the violation of human rights, the Western allies acquiesced in a Soviet demand for an amendment to the agreement setting up the Tribunal. This consisted in the removal of a comma, and this had the result of placing it beyond doubt that the violation of human rights was only an international crime when it was committed in furtherance of acts of aggression but not otherwise – thus precluding even the possibility that Stalin’s atrocities might one day be condemned by the international community.

In many ways the Nuremberg Trial seemed to be the solution to a practical problem: what was to be done with people like Göring or Hess? How to deal with their colleagues and the lesser fry who had run those terrible camps and had initiated the destruction of much of Europe? Churchill’s solution was to shoot them summarily but this was opposed by the Americans and the Soviets for, one may add, different reasons. As Schapiro points out, a number of eminent British lawyers supported the idea of the Nuremberg Tribunal, perhaps, not thinking about the consequences.

The consequences are with us in the shape of the completely useless international tribunals, the whole problem of what is a crime against humanity, the constant attempts made by transnational organizations to overcome decisions reached by duly elected democratic governments. There can be no world-wide democracy because it is impossible to create a world-wide rule of law.

Probably this will not count as Conservative history in any shape or form but it links in well with the previous posting about J. H. Elliott and Claudio Véliz, who gave the Anglosphere Institute’s inaugural lecture in Washington DC yesterday.

Probably this will not count as Conservative history in any shape or form but it links in well with the previous posting about J. H. Elliott and Claudio Véliz, who gave the Anglosphere Institute’s inaugural lecture in Washington DC yesterday.

Today is the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing on the island he named San Salvadore and the beginning of the exploration of the New World by the Old. It used to be called Discovery of America but Tory Historian understands that those are words not much in vogue these days. And, of course, one doesn’t quite know how to react to Columbus Day. It is celebrated in the United States by Italian-Americans (and there is a splendiferous memorial to the man himself at the bottom of Central Park, in Columbus Circle, in New York City) but in Latin American countries it is called various other things: Día de la Raza (Day of the Race – an odd name, given the descent of various peoples in Latin America), Discovery Day (not unreasonable though it does raise the question of what was discovered by whom and who knew about it before) and the newly named Día de la Resístancia Indigena (Day of the Indigenous Resistance) in Venezuela.

None of which manages to destroy the importance to European and, subsequently, world history of the day on which Columbus and others set foot on “a small island of the Lucayos, called, in the language of the Indians, Guanahani”.

For modern historians the argument has, as this blog has indicated before, shifted somewhat from the rather fruitless victim status competition to a discussion of the difference between the way the Spanish and British empires developed and the continuing difference between the countries of the Anglosphere and Hispanosphere.

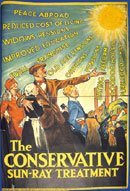

Tory Historian duly notes that co-blogger Iain Dale has already used the image sent by one of our readers. Nevertheless, it is worth saying on this blog as well:

Tory Historian duly notes that co-blogger Iain Dale has already used the image sent by one of our readers. Nevertheless, it is worth saying on this blog as well:

The present leader of the Conservative Party was not as original as he thought he was in his references to the sun being a Tory voter (at least, I think, that is what he said).

The poster on the left is one from the 1929 election. I am not sure it is a particularly useful example to look to. The Conservatives did not do particularly well. They won by a small margin the popular vote but lost 132 seats.

Labour under Ramsay Macdonald won a total of 287 seats and formed the government with the Liberals regaining some influence in what was a hung parliament.

Yet more memories from Tory Historian’s education. Another name to conjure with was J. H. Elliott, who had written about Imperial Spain. Professor Elliott, I am delighted to report, is still alive and very active, having just produced a new tome: “Empires of the Atlantic World”.

Yet more memories from Tory Historian’s education. Another name to conjure with was J. H. Elliott, who had written about Imperial Spain. Professor Elliott, I am delighted to report, is still alive and very active, having just produced a new tome: “Empires of the Atlantic World”.

This is a comparison between the Spanish and the British Empires in the Americas and some speculation about the reasons why they might have developed differently. As the TLS review by Fernando Cervantes points out, there is also a certain amount counter-factual speculation towards the end of the tome.

What would have happened if Henry VII had agreed to sponsor Christopher Columbus’s first voyage or if it had been an English expeditionary force that conquered Mexico? Would there have been a reversal in the two countries? Would England have remained Catholic, the strongest and most active of them in Europe? Or would the inherent national characteristics triumphed and there would have been a direct reversal?

“Would Latin America be a thrifty and pluralistic society, firmly entrenched in the capitalist economy of the First World, while North America was a collection of heavily indebted enclaves of outmoded forms of baroque culture?”How much of the different developments depended on the greater and more integrated control from Madrid than from London (though many of the local agents managed to lose instructions from both)? According to the reviewer this control worked towards the benefit of the Latin American colonies at the beginning. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth century they flourished, were considerably more civilized and, even, humane, especially towards the native population and the slaves. Once the control disappeared, however, it was the North American colonies that began to flourish, using the ideas they had imported and the structures under which they had lived. And the problem of slavery has not yet been tackled properly in many of the Latin American countries.

This is not the first comparison of this kind. After all, the difference between the two parts of the Americas is extraordinary and there have to be explanations for that. The first historian to raise the subject was Claudio Veliz in his “The New World of the Gothic Fox”, a book that became one of the basic texts of the Anglospheric thinking.

“According to Véliz, the dominant cultural achievements of Europe's English- and Spanish-speaking peoples have been the Industrial Revolution and the Counter-Reformation, respectively. These overwhelming cultural constructions have strongly influenced the subsequent historical developments of their great cultural outposts in North and South America. The British brought to the New World a stubborn ability to thrive on diversity and change that was entirely consistent with their vernacular Gothic style. The Iberians, by contrast, brought a cultural tradition shaped like a vast baroque dome, a monument to their successful attempt to arrest the changes that threatened their imperial moment.”It will be interesting to see to what extent Professor Elliott agrees with Claudio Veliz.

It is always sad to report the death of a talented historian, especially one as young as Ewen Green, whosed death at the age of 47 of multiple sclerosis has just been reported.

Dr Green has been a remarkable historian of the Conservative Party in the twentieth century, starting with "The Crisis of Conservatism", published in 1995. This was followed by "Idologies of Conservatism" in 2002 and the very recent short biography of Margaret Thatcher.

As the obituary in today's Guardian says:

In a sense, it completes a trilogy. The first book looked at Edwardian politics through Thatcherite spectacles, detecting the emergence of a radical strain of Conservatism. After the variations developed in the second, the final book suggests that, in the perspective of history, Thatcherism itself was not quite as novel as it first seemed.Some of our readers might feel that another comment made by the author of the obituary is a little too amusing though very apt:

His originality lay in seeing there had been too much concentration on the ideas and politics of the left in 20th-century Britain, probably because many historians were themselves left of centre. He saw that the response of the right was in need of proper investigation, especially by historians who were not of the right themselves.We expect numerous comments on whether Dr Green was, indeed, "the most stimulating historian of the 20th-century Conservative party".

His whole career revolved around the paradox that he became the most stimulating historian of the 20th-century Conservative party without ever being tempted to vote for it.

As my co-blogger put up a posting that is seriously modern (though, I suppose, both Blair and Brown might be on their way to being history), I thought I might stay in the second half of the twentieth century as well. (OK, Iain, just joking. I know RAB Butler is history.)

As my co-blogger put up a posting that is seriously modern (though, I suppose, both Blair and Brown might be on their way to being history), I thought I might stay in the second half of the twentieth century as well. (OK, Iain, just joking. I know RAB Butler is history.)

The intriguing story of George Blake, one of the most successful Soviet spies, being awarded £4,690 by the European Court of Human Rights because the Attorney General had taken too long to bring about the government’s action against Blake to prevent him from profiting by his treachery brings back all kinds of memories of the Cold War. But above all, it raises problems of the naming of matters.

The Daily Telegraph has two articles on the subject, one by Joshua Rozenberg on the legal side of the decision and the other one by Phillip Knightley, a brief summary of Blake’s career.

Both the articles refer to Blake as a double agent. Now, the truth is that there is no such thing as a double agent. There are, or have been in the past, people who will spy for the highest bidder and may, therefore, spy for several countries and organizations simultaneously. But in the world of ordinary espionage there is but one true employer.

Blake was a Soviet agent who pretended to be a British Intelligence officer, the better to carry out his work for his real paymasters and ideological controllers. He was also a man responsible for numerous deaths of Soviet officers whom he had tried to persuade to defect to the West. Curiously enough, Mr Knightley describes the operation that was set up in Berlin but does not mention what might have happened to the unfortunate victims of the KGB-run sting operation.

That brings me to another problem of vocabulary: who is an agent and who is a spy? It used to be really easy to define: our people were agents, theirs were spies. Any film of the thirties, forties or fifties will tell you that. There was the odd complication, as one can see in the novels of Buchan, for example, or Erskine Childers’ “Riddle of the Sands” about the distinction between those who spied for their country and could, therefore, be called German agents, and those who spied for Germany, though they were British. The latter were clearly spies and traitors.

This distinction between agent and spy exists in most countries and languages. It is, however, being eroded in Britain. Not only we keep talking about double agents when we really mean enemy spies but there is a curious tendency to refer to British agents as British spies (and not by the Russians, either).

William Boyd’s latest book, “Restless”, for instance, centres on a seemingly ordinary elderly English lady who turns out to be Russian by birth who was a British "spy" during the war in occupied France. Undoubtedly a dangerous assignment and one that the survivor might not want to talk about subsequently. But the implication from the blurb is that the lady in question has tried to bury the truth as being shameful and traumatic while her daughter is shocked and upset when she finds out.

Oh really? Most people are rather intrigued and not a little proud if they find out that their parents were British agents fighting the Nazis during the war. On the other hand, according to Mr Boyd those agents were really spies and, therefore, morally dubious. Much depends on the name.

I didn't see it but I understand Tony Blair gave a brilliant speech this afternoon. However, one passage which people may not have picked up on was when he described Gordon Brown as a "Great Servant of the State". Those of you who know your history will be aware that this is exactly hwo Harold Macmillan described RAB Butler - and it wasn't meant as a compliment. Of course, Rab Butler never got to be Prime Minister. I understand Cherie looked particularly pleased at that point.

Tory Historian is one of those thousands who studied the Tudors’nStuarts for A-level and is, therefore, a paid up member of “Sir Geoffrey Elton is the greatest historian ever” club. After a week of rather hard, concentrated work on various projects, a reading of the great man’s “The Practice of History” seemed in order.

Tory Historian is one of those thousands who studied the Tudors’nStuarts for A-level and is, therefore, a paid up member of “Sir Geoffrey Elton is the greatest historian ever” club. After a week of rather hard, concentrated work on various projects, a reading of the great man’s “The Practice of History” seemed in order.

An admission is in order: I had no idea until I looked up Elton’s biography, that he was of a German Jewish family, which had moved to Prague before fleeing again to Britain. Another loss to Germany and gain to Britain as a result of that insane ideology.

A couple of quotations, I think, for readers to contemplate. A characteristically wry comment at the very beginning:

[M]ost books on history have been written by philosophers analysing historical thinking, by sociologists and historiographers analysing historians, and by the occasional historian concerned to justify his activity as a social utility. This contribution seeks to avoid the last, ignores the second, and cannot pretend to emulate the first. It embodies an assumption that the study and writing of history are justified in themselves, and reflects a suspicion that a philosophic concern with such problems as the reality of historical knowledge or the nature of historical thought only hinders the practice of history.This is a very misleading comment as far as Sir Geoffrey himself is concerned. In actual fact, he spent a great deal of time (though not as much as he did on the unravelling of the Tudor years) on thinking and writing about history, its meaning and importance.

The second quotation is particularly apt in the days after the kerfuffle about Pope Benedict XVI’s extremely interesting lecture at the University of Regensburg, in which he spoke of the role of reason in religion and the “synthesis between the Greek spirit and the Christian spirit”.

This is what Sir Geoffey has to say about the unique growth of the study of history in European culture:

There is something markedly a-historical about the attitudes embedded, for instance, in the classic minds of India and China, and any history of historiography must needs concentrate on the Hellenic and Judaic roots of one major intellectual tree. No other primitive sacred writings are so firmly chronological and historical as is the Old Testament, with its express record of God at work in the fates of generations succeeding each other in time; and the Christian descendant stands alone among the religions in deriving its authority from an historical event.One could not compete with the elegance of that statement. I would put it simpler: history is studied in cultures which are based on a sense of curiosity. “What happened then?” – is a question all those who have had to deal with children know all too well. It is the first question of an historian.

On the other hand, the systematic study of human affairs, past and present, began with the Greeks. Some sort of history has been studied and written everywhere, from the chronicles of Egypt and Peru to the myths of Eskimos and Polynesians, but only in the civilization which looks back to the Jews and Greeks was history ever a main concern, a teacher for the future, a basis of religion, an aid in explaining the existence and purpose of man.

The Conservative History Group will be holding a fringe meeting at the Party Conference at 5pm on Monday 2 October. Lord (David) Trimble will be the guest speaker and will talk about the history of the Ulster Unionists. The meeting will be chaired by Keith Simpson MP.

Venue: Granville Suite, Trouville Hotel, Priory Road, Bournemouth

It is outside the secure zone and you do not need a conference pass to attend.

Bear with me. These musings will be worth reading, particularly when they are turned into an article for the Journal.

Bear with me. These musings will be worth reading, particularly when they are turned into an article for the Journal.

The theme of what is English or what is important to all the countries, Britain, America and those of the Empire and Commonwealth, understandably, preoccupied many of the film-makers. The ideas are there in straightforward war films like “In Which We Serve” – duty of service but also private affection and love of those close to one with little emotion displayed – or “The Way Forward”, which shows the birth and growth of the new, more democratic army, with even the officer, played by David Niven, being one who had risen from the ranks.

The most successful if somewhat eccentric of the “what we are fighting for” films are those made by Michael Powell and Emerich Pressburger (himself a Hungarian), such as “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp”, a strongly argued case for ordinary decency that uses the image, created by David Low and so despised by the Left, of the bumbling old-fashioned colonel, out of date in the brave new world. The film makes it clear: being out of date is not the worst thing that can happen to one, if it means adhering to old-fashioned honesty and decency.

Churchill did not like the film and, I think, I can understand why. The trouble with Blimp is that he is not terribly bright, while the only highly intelligent decent man in the film is his German friend, played by Anton Walbrook, who escapes from Nazi Germany and tries, without much success, to warn his British friend of the evil that is brewing in that country. I can imagine that Churchill was not too keen on any film that perpetuated the great British assumption that intelligence is somehow bad and suspect.

The Powell-Pressburger films deserve a posting all to themselves but I do need to mention their most audacious attempt to build up a picture of England as the country that is worth fighting for with the true values that needed to be carried on beyond this battle against evil: “The Canterbury Tales”.

While Churchill was not very fond of “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp” he was, predictably, enamoured with the various historical films of those years, his favourite one being “That Hamilton Woman”, which Tory Historian has never seen, despite it stellar cast.

It is normal for countries to produce historical films during a war and even as one looms on the horizon. What the historical theme might be depends largely on the way that country sees itself. Most of the British ones dealt with the previous times when the country faced up to a strong enemy on the Continent, the two favourite topics being the Spanish Armada and the Napoleonic Wars.

Another film Churchill was rather fond of was “The Young Mr Pitt”, also seen by Tory Historian on that Bank Holiday week-end (one to remember, clearly). Film critics, of whom Tory Historian is most definitely not one, tend to be a bit sniffy about this film. Oh dear, they say, it is so simplistic. We know so little about the reality of the political battle between Fox and Pitt. Not enough is made of the great battles won by Nelson. And, honestly, how … well, really, … how one-sided.

War films do need to be simplistic to a great extent. You can’t afford to let doubts creep in when the country is at risk, as it was when “The Young Mr Pitt” was made in 1941. Unusually for Reed, the shooting and the post-production took a long time and the film was not released till 1942 by which time the United States, part of the targeted audience, was at war.

If “Night Train to Munich” was a pre-Dunkirk film, this one is definitely post-Dunkirk. The mood is mostly dark, though, clearly, there are a few victories reported, notably that of the Nile and Trafalgar. Pitt, we have to remember, died when the Continental menace still loomed large.

“The Young Mr Pitt” is a remarkably skilful film, with quick episodes following one another to give an impression of the great prime minister’s career rather than a historical dissection of it. It is not inaccurate, merely impressionistic.

There is a clear link to Churchill, Pitt the Younger being the one man on whom the salvation of the country depends, as the scene where his temporary successor Addington is harassed by MPs shows. There is, also, the clearly designated American connection, it being of great importance to show that Britain at all times fights for the principles the United States was founded on and lives by.

At the very beginning of the film we see Pitt the Elder, the Earl of Chatham, speaking in the House of Lords against the war with the Colonists, proclaiming: “You will never conquer America.” He refers the ideas of liberty, the language and religion that the two countries have in common. This is echoed later by the younger Pitt, when he denounces revolutionary and Napoleonic France as being inimicable to English ideas of liberty and wanting to impose its language and its irreligion on this country.

That, in a way, is the summary of what Britain is fighting for: her language, her religion, her ideas of liberty.

Unlike other war-time films, this one does not show the people en masse in a good light, taking its cue from Shakespeare and his fears of the mob. Individuals, like the two pugilists who support Pitt through thick and thin, or William Wilberforce (played by John Mills) who longs for peace but has to accept war, come out well. Even Fox offers to serve under Pitt when it becomes clear that nothing but all-out war will serve Napoleon’s purposes.

But the people – oh the people are fickle. If there is a victory, they support Pitt. As soon as things go wrong, they throw bricks at his windows and rotten eggs at his carriage. One wonders whether this was a realistic picture of the mood in Britain in 1941 (without the bricks and the rotten eggs).

The film hinges on the great Robert Donat’s performance. Carol Reed had enticed him back to film-making because they both considered this to be important war work. He himself was of English, Polish and German descent, which accounts for the slightly odd surname but, like Leslie Howard, managed to play the quintessential English hero with no difficulty.

In “The Young Mr Pitt” his performance is superb and all the film’s shortcomings are swallowed up in that. He plays the aged Earl of Chatham as well as Pitt the Younger, whom he takes through from his early political years, when the bouncy young man can barely control his elation at being made prime minister at the age of 24 and has pillow chases up and down the stairs with the young siblings of Lady Eleanor Eden with whom he is obviously in love, through the hard-working, hard-drinking dark days, to the triumph of his post-Trafalgar speech at the Guildhall. The shadow of his early death hangs over that event and Pitt’s defiant toasting of his friends with wine rather than the medication poured out to him by his doctor.

As I have mentioned in a previous posting, Pitt the Younger is presented as a romantic hero, the man who sacrifices his personal happiness and his life to his country and the idea of liberty, which his country represents. The country’s liberty and that of its individual people, that is what Britain fought for in the Napoleonic Wars and that is what it was fighting for in 1941. A simple, comprehensible, and all-embracing idea.

This is turning into a more serious experiment than predicted. I ought to have known that I could not do a blog of readable length on so many related subjects.

This is turning into a more serious experiment than predicted. I ought to have known that I could not do a blog of readable length on so many related subjects.

“Night Train to Munich” is often described as almost a continuation of Hitchcock’s “The Lady Vanishes”, which also stars Margaret Lockwood. The Reed film had Rex Harrison instead of Michael Redgrave who had other commitments and revived the cricket-loving Charters and Caldicott as played by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne.

It is, of course, a truism among film critics (of whom Tory Historian is most definitely not one) that Alfred Hitchcock was one of the greatest and few can come up to his standard. Well, in this case, the truism is wrong. “The Lady Vanishes” is a delightful film, full of the usual Hitchcockian touches and also full of the man’s ineffable silliness. Plots? What plots?

“The Lady Vanishes” takes place in a country that is vaguely Ruritanian, gives the impression of being Switzerland but is possibly Germany. Or not. This lack of precision or any worry about it diminishes the tension of the story. After all, it is only fairyland and the good will triumph while the bad will come to a no good end.

“Night Train to Munich” is very different. It is timed and positioned precisely, taking place in the last few months before the outbreak of World War II, finishing in the train journey that takes place in the night of September 3, 1939 and a chase through Germany the following day, with a final escape to Switzerland.

Briefly: the British manage to spirit out a Czech scientist, who is working on a development in arms manufacturing that will revolutionize warfare, just ahead of the invading Germans. But the Gestapo arrests his daughter as she is trying to reach the airport and sends her to an internment camp.

Immediately, one must note two very precise and realistic aspects. When the Germans talk about Czech steel production being superlative and their need for the armaments manufacturing in Czechoslovakia, the film tells the truth. The Czechoslovakia of the late thirties was one of the best producers of arms in Europe and the Germans were fully aware of this. As they took the factories of Sudetenland over, they transferred some to Austria and used others in situ. Czech tanks and vehicles were invaluable in the invasion of Poland and, later, of the Soviet Union.