A bit odd, what? Here we are running a blog for Conservative historians, conservatives, historians and any combination of that and no comments. Well, a couple. At first, there was a technical problem caused entirely by Tory Historian’s ionefficiency. But that has been cleared up and … well, still no comments.

A bit odd, what? Here we are running a blog for Conservative historians, conservatives, historians and any combination of that and no comments. Well, a couple. At first, there was a technical problem caused entirely by Tory Historian’s ionefficiency. But that has been cleared up and … well, still no comments.

It’s not as if Conservative historians had nothing to say for themselves usually. A more vociferous lot it is hard to imagine. Perhaps, it is the postings that have not been ones to inspire discussion. Well, there is an opportunity to rectify that. Send in postings or ideas for postings. We are ready to discuss matters.

Or just put up a comment that disagrees with the posting. Or tells us that it is a silly waste of space.

More seriously (I think) it is time for all of our readers to think a bit about contributions to the Conservative History Journal. The issue due out in June aims to have several pieces on conservative foreign policy in its various manifestations. The autumn one will concentrate on women in the Conservative Party.

In a never-ending pursuit of excellence Tory Historian has, somewhat reluctantly, learnt some more about the technology of blogging, to wit how to illustrate postings. Here are two pictures of one of the best-known Conservative Prime Ministers and godfather of political spinners, Benjamin Disraeli. The first one is a delightful sketch by the Irish artist, Daniel Maclise (or possibly, somebody copying Maclise), unfortunately not on display at the National Portrait Gallery. This is Disraeli the dandy.

The first one is a delightful sketch by the Irish artist, Daniel Maclise (or possibly, somebody copying Maclise), unfortunately not on display at the National Portrait Gallery. This is Disraeli the dandy.

The second one is by an artist who is seriously underestimated, in Tory Historian’s opinion: Sir John Everett Millais, for ever associated with the Effie Ruskin scandal and the obnoxious “Bubbles” picture.  Millais was a very fine portraitist, who concentrated on the essence of his subject. There is a matching portrait of W. E. Gladstone but we could not possibly reproduce that on this blog.

Millais was a very fine portraitist, who concentrated on the essence of his subject. There is a matching portrait of W. E. Gladstone but we could not possibly reproduce that on this blog.

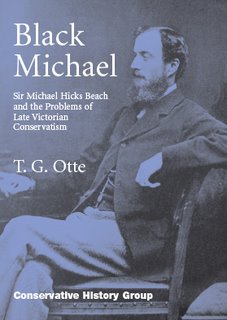

Not only a meeting today but a special supplement to the Journal: an essay on Sir Michael Hicks Beach by T. G. Otte of the University of East Anglia, a frequent contributor to the Journal.

Not only a meeting today but a special supplement to the Journal: an essay on Sir Michael Hicks Beach by T. G. Otte of the University of East Anglia, a frequent contributor to the Journal.

The paper looks at the career of an important but curiously neglected Conservative politician of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. It deals with political shenanigans as well as certain firmly held ideas.

The tension between Conservatives who believed in a less adventurous foreign policy and well balanced budgets and those who cared less about fiscal rectitude and more about the Empire and Britain’s role in the world (sounds familiar?) is carefully outlined.

A good read, even though we say so ourselves. Available from Politico's.

Unfortunately Peter Mangold has had to pull out of our speaker meeting tomorrow. Lord (Tim) Renton has stepped into the breach and will give a talk on Chief Whips. The venue is Committee Room 16 of the House of Commons and the meeting will run from 6.30 to 7.30pm.

This is a posting for all those conservatives and historians of various denomination and, indeed, people who are interested in history and conservative ideas without practising the first or sharing the second, who are tired of apologies for the past.

Apologizing for the past is a particularly silly and unhistorical idea. (And, of course, two days after the anniversary of Hitler’s birth and on the day of the anniversary of Lenin’s it does occur to one that those of us who do not believe in utopias have very little to apologize for, anyway.)

One hears a great deal of sneering about the Whig theory of history that imposed a certain view, contemporaneous with the historians, on the past. That view showed the world developing in a certain way, towards a brighter future, as laid down by the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and its descendants.

Right, so we dismiss that view. But how much better is the one that says we must apologize for something our ancestors, who lived in different circumstances, whose actions were governed by different ideas did? There is a rather ridiculous posturing of one’s own superiority. We can see how wrong they were and we must apologize for it.

Oscar Wilde, not a conservative historian but a more interesting writer than many people will allow, put it much better in his The Critic as Artist:

“There is no essential incongruity between crime and culture. We cannot re-write the whole of history for the purpose of gratifying our moral sense of what should be.”In any case, future generations will have very different notions of morality and they will discard our own self-regard as being inadequate.

.... to all those who have tried to leave comments on this blog. Technical incompetence on the part of Tory Historian (well, what would you expect) meant that these comments did not actually appear. This has now been rectified and we all look forward to a spirited discussion.

Today marks the anniversary of the first publication of what is considered by most people to be the first modern detective story, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” in Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine in 1841.

Why should this date be noted on a Conservative History blog? Simply, because in my opinion, the real detective story is a truly conservative form of literature in its main aspects. It is also, very much an Anglospheric form, with other countries and cultures largely imitating the British and American genre.

What happens in a detective story? A crime is committed (usually murder, though that might be the eventual outcome and in the nineteenth century tales that was not necessary) and it is considered to be wrong. If the crime is murder then it is obvious that the accepted order has been upset to the point when the hero or heroine will not rest until it is restored.

Individual life is important; sense of property is important. These are conservative ideas and Anglospheric ideas. How different from all those utopias we have seen in the twentieth century, which merrily discard any sense of order, property, or the absolute importance of human life in order to create a system that appeals to a few people and that result inevitably in slave labour camps.

And, whether victim, criminal or detective, the story is concerned with individuals and their choices. Punishment may not be meted out to the criminal directly (Holmes lets off several people, for instance, for various reasons) but it is clearly defined that actions follow choices made and are, in turn, followed by consequences.

Many of our readers will be shocked to see that we are celebrating or commemorating the first battle of that mighty rebellion. That was the consideration that prevented me from writing about Paul Revere's ride yesterday (that, and my inability to rid my memory of the other Paul Revere in Guys and Dolls "I gotta horse right here/ his name is Paul Revere").

The American Revolution, however, was in many ways the second English civil war and certainly a civil war within what we now call the Anglosphere. Furthermore, many of its principles were conservative, though the Tories at the time were clearly determined to bring the upstart rebels down.

And it's a cracking good tale. So here is the account of the battle of Lexington Green, as posted on Chicagoboyz.

Easter week seems a good time to think about the past and the future. This blog is offering two quotations on which one can meditate. They are about a thousand years apart but both very apposite.

The first is from Archbishop Wulfstan who lived from 1009 to 1095 (not a bad span for that age and even for ours), was Bishop of Worcester and Archbishop of York. He wrote civil and ecclesiastical legal codes and a number of homilies.

His Sermo Lupi ad Anglos ("Wulf's Address to the English", c. 1014 AD) consists of ferocious denunciations of the morals of his time, so, I think, he can be counted as a conservative. Among other things he said:

“There is also a need that each should understand where he came from and what he is -- and what will become of him.”The second quotation is from the great American conservative philosopher and columnist, Russell Kirk, who was largely responsible for the revival of consevative thought in the United States.

This is one of his “Conservative Principles”, which formed the second chapter of The Politics of Prudence:

“Third, conservatives believe in what may be called the principle of prescription. ... Conservatives sense that modern people are dwarfs on the shoulders of giants, able to see farther than their ancestors only because of the great stature of those who have preceded us in time.”How many of us can seriously disagree with that?

On April 15, 1755 the following advertisement appeared in the London press:

“A Dictionary of the English language: in which the words are deduced from their originals and illustrated in their different significations by the best writers. To which are prefixed a History of the Language and a Grammar. By Samuel Johnson A.M.”Dr Johnson’s great dictionary was published and the best known definition of a lexicographer “a harmless drudge” was first presented to the public.

In his entertaining history of “Dictionary-makers and the dictionaries they made”, entitled Chasing the Sun, Jonathon Green charts the various attempts to imitate the Italians and the French by creating either an English Academy to codify the language or writing a Dictionary for the same purpose; possibly both.

Dr Johnson, too, saw his magisterial work that he had begun in 1745, as a patriotic exercise, writing in the Preface:

“I have devoted this book, the labour of my years, to the honour of my country, that we may no longer yield the palm of philology to the nations of the continent.”As Mr Green points out, Dr Johnson and his Dictionary were highly regarded by such writers as Voltaire; the high regard was not reciprocated on this side of the Channel.

Johnson had, as he explained, intended to “fix” the language, to offer precise definitions, rules and etymologies. While he succeeded in creating the schema of a dictionary, he realized that a language, particularly the English language cannot be “fixed” or defined for any length of time – it is too fluid, too flexible.

Besides, he felt that trying to “fix” the language actually went against the English concepts of freedom.

On the other hand, he did use the Dictionary, as he used the essays in the contemporaneous Rambler to advance his own High Tory, High Church, moral view of the world through his definitions and quotations (often re-written to suit himself).

The Dictionary was praised by many, particularly David Garrick in verse, assessed soberly by Adam Smith and attacked by prominent Whigs for being Tory. This may have had something to do with Johnson’s definition of a Tory as

“one who adheres to the ancient constitution of the state, and the apostolical hierarchy of the church of England”.The Whigs, on the other hand, were defined as a “faction”.

Garrick’s rollicking verse displayed the patriotic aspect of the whole enterprise and the Dictionary’s reception:

“Talk of war with a Briton, he’ll boldly advance,The forty French refers, naturally, to the French academicians who have been codifying the French language with variable success since the days of Cardinal Richelieu. (The Académie was founded in 1535)

That one English soldier will beat ten of France;

Would we alter the boast from the sword to the pen,

Our odds are still greater, still greater our men …

First Shakespeare and Milton, like gods in the fight,

Have put their whole drama and epick to flight …

And Johnson, well arm’d like a hero of yore,

Has beat forty French, and will beat forty more!”

The poetic critique was published in the Public Advertiser and the Gentleman’s Magazine. Can any modern reviewer rival that?

This is what Andrew Roberts, the first conservative historian to be interviewed for the Conservative History Journal wrote this in his “Napoleon and Wellington” about April 12, 1814:

“[Marshal] Soult withdrew the next day to Carcassonne, leaving most of his guns and 1,600 wounded, and at noon on 12 April Wellington entered the city of Toulouse. He found that the stone eagles had been pulled off the administrative buildings there and Napoleon’s statue had been thrown out of the window of the Capitol. He saw the Bourbon white flag flying everywhere, ‘and everybody wearing the white cockade’ of the Legitimist monarchy of Louis XVIII.That picture of Wellington dancing the flamenco as a flourish of his own private celebration of the end of the gruelling Peninsular campaign goes a long way towards explaining why the Duke of all Britain’s military and political men is held not just in high esteem but great affection, as he was by his own soldiers and officers.

At 5 p.m. that day Colonel Frederick Ponsonby of the 12th Light Dragoons, the emissary from Allied headquarters, found Wellington in his shirtsleeves, pulling on his boots. ‘I have extraordinary news for you,’ Ponsonby said. ‘Ay, I thought so. I knew we should have peace; I’ve long expected it,’ answered Wellington. ‘No; Napoleon has abdicated. ‘ ‘How abdicated!’ Wellington cried. ‘Ay, ‘tis time indeed. You don’t say so, upon my honour! Hurrah!’ Wellington then turned on his heel and snapped his fingers in a triumphal pastiche of a flamenco dance. The

Peninsular War was over.”

The book, incidentally, is a cracking good read and, as one would expect, superbly well researched history.

Today marks the 400th aniversary of the decree issued by King James I of England and VI of Scotland that united the Cross of St George (red on a white background) and that of St Andrew (diagonal white on a blue background) in the first version of the Union Flag.

The Cross Saltire of St Patrick (diagonal red cross on a white background) was added after the Act of Union and the Union Flag as we know it now was first flown on January 1, 1801.

Why no Welsh Dragon? Simple really. Wales, a Principality, had, by 1606, been a part of England for several centuries.

One thing that has always puzzled me is how do people know when the Union Flag (or Union Jack) is flown upside down, which a sign of distress. As far as I can make out after careful scrutiny it is completely symetrical. It seems, that I had better go on scrutinizing it a bit more. According to the Buckingham Palace press office:

“The Union Flag is flown correctly when the cross of St Andrew is above that of St Patrick at the hoist (as the earlier of the two to be placed on the flag, the cross of St Andrew is entitled to the higher position) and below it at the fly; in other words, at the end next to the pole the broad white stripe goes on top.”Why is it sometimes called the Union Flag and sometimes the Union Jack? On the whole, we accept that it is the Flag on land and Jack on the seas. But there seems to be some doubt as to the origin of the words Union Jack.

“The term Union Jack possibly dates from Queen Anne's time (reigned 1702-14), but its origin is uncertain. It may come from the 'jack-et' of the English or Scottish soldiers; or from the name of James I who originated the first union in 1603, in either its Latin or French form Jacobus or Jacques; or, as 'jack' once meant small, the name may be derived from a royal proclamation issued by Charles II that the Union Flag should be flown only by ships of the Royal Navy as a jack, a small flag at the bowsprit.”The British are not, on the whole, a flag-flying nation, having not felt the need for it in the past. Indeed, one of the most telling episodes in Kipling’s “Stalky and Co” is that describing a visit to the school by a politician who talks much of the flag and even produces one from his breast pocket. The boys, staunch patriots every one, feel besmirched by his flag-waving.

There are times when flags are in order. One of those was the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations in the Mall, that was a sea of flags: Union Flags, English flags, Scottish and Welsh flags, Canadian, Australian and various African flags, even one solitary and very stylish Isle of Man flag.

After 7/7 I noticed that the Union Flag was flown more frequently than is usual, it being controlled by carefully laid down rules. In time of trouble, the flag was being used as a symbol of defiance.

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, which will require a special trip to Paddington railway station, it being the nearest surviving monument to the man’s genius.

As Richard Savill wrote in the Daily Telegraph the other day:

“The vision of Brunel - who by the time of his death in 1859, aged 53, had built 25 railway lines, more than 100 bridges and three ships - helped transform the West Country during the Victorian era.”It also helped to transform Britain, as Richard Alleyne pointed out on the same day:

“Along with a handful of other industrialists he transformed the country from a traditional, rural, agrarian economy to a modern, urban, industrial one. By the time of his death, it was the industrial superpower of the world.”A legacy to be proud of and a man, whose loss to Britain cost France dear. I can’t help wondering about a comment made by Andrew Kelly, the director of Brunel 200:

“Although Brunel was born 200 years ago, his influence remains with us in Britain today.I appreciate the need to encourage the Brunels of the future but what makes the man think that someone born 200 years ago is of little relevance. I seem to recall that in a recent BBC poll for the greatest Englishman, Brunel came second to Sir Winston Churchill.

We hope that by showcasing his huge breadth of mind, and how he excelled as an engineer, ship designer, architect, surveyor and artist, we will encourage the Brunels of the future to adopt his 'can do' attitude and determination to achieve.”

Mr Kelly must realize, surely, that apologizing for the past is not the way to build the future. He could start by meditating on Edmund Burke’s sayings.

They are celebrating in Rotherhithe as well.

In his brief but exhaustingly dashing analysis of the “European Question and the National Interest”, professor Jeremy Black makes an interesting comment about the Hundred Years' War.

In the 1330s, as France and England drifted towards war it became rather awkward for the aristocracy to continue with what we would now call international and francophile outlook and behaviour.

In particular, the question of the language became acute. The use of English as it had developed from mixed Anglo-Saxon and Norman roots became a matter of patriotic political tool.

“In 1344, it was claimed before the House of Commons, an important and indicative choice of location, that Philip VI of France was ‘fully resolved … to destroy the English language, and to occupy the land of England’. As the lower classes spoke English anyway, it was only a shift by the upper classes that was at issue.”There is but a short step from that to the first two great literary works in English: John Gower’s Confessio Amantis and, above all, Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

Continuing our series of inspiring quotations, we turn to the great French conservative historian, sociologist, political writer and politician, Alexis de Tocqueville. His two great books, Democracy in America and The Ancien Regime and the French Revolution, as well as his shorter works are full of goodies and the English translations are, in some ways, easier to read than Burke’s pronouncements.

Here are two examples from the first of those works:

“When the past no longer illuminates the future, the spirit walks in darkness.”

“Democracy and socialism have nothing in common but one word, equality. But notice the difference: while democracy seeks equality in liberty, socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude.”The first explains and justifies the study of history, the second explains why so many of us are now conservatives.

I'm delighted to use my inaugural post to announce the launch of the Conservative History Group Website which you can get to by clicking HERE. After a period of relative inactivity due to my involvement in the last election and the ensuing leadership campaign, this year promises to be rather more exciting for the Conservative History Group. If you've got any ideas of how we can improve the website and what kind of information we should consider adding to it, do email me iain AT iaindale DOT com

On April 5, 1955 Sir Winston Churchill resigned as Prime Minister because of failing health. Alternatively, one might say, he was finally persuaded by his despairing colleagues that the state of his health could no longer be hidden from the relatively inquisitive media (can anyone imagine the media not commenting on such facts now?) and the public.

The BBC’s historical archive has an article and a video of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh arriving on the previous evening at Number Ten for a dinner, hosted by the Prime Minister and Lady Churchill.

It is so difficult to summarize or even be fair about Churchill’s career. Perhaps, we should have an issue of the Conservative History Journal dedicated to it. At the very least, a meeting might be a good idea. But, sadly, the great man’s second ministry was a mistake, not just because of his age and health but because of his socialistic, Whig paternalistic views of domestic politics.

Many of the problems the country faced in the subsequent decades may have been created during and immediately after the war but they were intensified under Churchill's peacetime premiership.

Backbenchers that is. Yes, they exist but do they have any importance? This melancholy thought occurred to me as I read the obituary of Sir Anthony Beaumont-Dark, in his day a well-known backbench MP and, as the Daily Telegraph diplomatically puts it, “an outspoken and populist” one at that.

“Outspoken and populist” comes into the same category as “frank and open”. In other words, the man was rude about anyone he did not quite approve of. And despite his denials, it is clear that many of those off the cuff comments were made with the newspapers or, at least, their gossip columns, in mind.

His views seem to have been rather “wet” Tory, protectionist, statist, suspicious of trade. One could argue that he represented the point of view of the very old-fashioned Tory squirearchy.

One of his comments caught my attention and prompted the musings at the top:

“I believe a backbench MP who is prepared to stick his neck out plays just as important a part as a cabinet minister whom nobody remembers.”As it happens, he probably did not play quite as important a part as that would indicate but he fought his corner and made his views clear. What else should politicians be doing? And who remembers the ministers he tussled with?

It seems that Marcus Tullius Cicero (c. 106 - 43 BC) may have had an unsuspected strain of puckish humour. This is what he said about history and historians:

I expect it applies to conservative historians, though.

I knew a quotation or two from Edmund Burke will bring the best out of our readers. Lexington Green, a stalwart Anglospherist from the other side of the Pond (the former colonies) sent us the following from Burke's Speech on Conciliation with America:

"As to the wealth which the Colonies have drawn from the sea by their fisheries, you had all that matter fully opened at your bar. You surely thought those acquisitions of value, for they seemed even to excite your envy; and yet the spirit by which that enterprising employment has been exercised ought rather, in my opinion, to have raised your esteem and admiration.Like the puddings of the eighteenth century English kitchen Burke is a little too rich for modern taste. But how many plums there are.

And pray, Sir, what in the world is equal to it? Pass by the other parts, and look at the manner in which the people of New England have of late carried on the whale fishery. Whilst we follow them among the tumbling mountains of ice, and behold them penetrating into the deepest frozen recesses of Hudson's Bay and Davis's Straits, whilst we are looking for them beneath the arctic circle, we hear that they have pierced into the opposite region of polar cold, that they are at the antipodes, and engaged under the frozen Serpent of the south.

Falkland Island, which seemed too remote and romantic an object for the grasp of national ambition, is but a stage and resting-place in the progress of their victorious industry. Nor is the equinoctial heat more discouraging to them than the accumulated winter of both the poles. We know that whilst some of them draw the line and strike the harpoon on the coast of Africa, others run the longitude and pursue their gigantic game along the coast of Brazil.

No sea but what is vexed by their fisheries; no climate that is not witness to their toils. Neither the perseverance of Holland, nor the activity of France, nor the dexterous and firm sagacity of English enterprise ever carried this most perilous mode of hardy industry to the extent to which it has been pushed by this recent people; a people who are still, as it were, but in the gristle, and not yet hardened into the bone of manhood.

When I contemplate these things; when I know that the Colonies in general owe little or nothing to any care of ours, and that they are not squeezed into this happy form by the constraints of watchful and suspicious government, but that, through a wise and salutary neglect, a generous nature has been suffered to take her own way to perfection; when I reflect upon these effects, when I see how profitable they have been to us, I feel all the pride of power sink, and all presumption in the wisdom of human contrivances melt and die away within me. My rigor relents. I pardon something to the spirit of liberty."

We are starting a series of quotations of conservative nature; words of (possible) wisdom uttered by writers, thinkers, even politicians. And who better to start with than Edmund Burke, the man who, though a Whig for most of his political career, laid the foundation of much of the thinking that the Conservative Party follows (from time to time) and who has inspired generations of conservatives.

Here are two from Reflections on the Revolution in France:

“The state includes the dead, the living and the coming generations.”

“People will not look forward to posterity who never look back to their ancestors.”I am reading Conor Cruise O’Brien’s biography of Burke, so there will be more postings on the subject in the coming days and weeks. There will be other quotations as well. No doubt, readers of this blog have their own favourites and will want to post them.

Links

Followers

Labels

- 1922 Committee (1)

- abolition of slave trade (1)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- academics (2)

- Adam Smith (2)

- advertising (1)

- Agatha Christie (4)

- American history (33)

- ancient history (4)

- Anglo-Boer Wars (1)

- Anglo-Dutch wars (1)

- Anglo-French Entente (1)

- Anglo-Russian Convention (2)

- Anglosphere (19)

- anniversaries (175)

- Anthony Price (1)

- archaelogy (8)

- architecture (8)

- archives (3)

- Argentina (1)

- Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams (1)

- art (14)

- Arthur Ransome (1)

- arts funding (1)

- Attlee (2)

- Australia (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Baroness Park of Monmouth (1)

- battles (11)

- BBC (5)

- Beatrice Hastings (1)

- Bible (3)

- Bill of Rights (1)

- biography (21)

- birthdays (11)

- blogs (10)

- book reviews (8)

- books (78)

- bred and circuses (1)

- British Empire (7)

- British history (1)

- British Library (9)

- British Museum (4)

- buildings (1)

- businesses (1)

- calendars (1)

- Canada (2)

- Canning (1)

- Castlereagh (2)

- cats (1)

- censorship (1)

- Charles Dickens (3)

- Charles I (1)

- Chesterton (1)

- CHG meetings (9)

- children's books (2)

- China (2)

- Chips Channon (4)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (1)

- cities (1)

- City of London (2)

- Civil War (6)

- coalitions (2)

- coffee (1)

- coffee-houses (1)

- Commonwealth (1)

- Communism (15)

- compensations (1)

- Conan Doyle (5)

- conservatism (24)

- Conservative Government (1)

- Conservative historians (4)

- Conservative History Group (10)

- Conservative History Journal (23)

- Conservative Party (25)

- Conservative Party Archives (1)

- Conservative politicians (22)

- Conservative suffragists (5)

- constitution (1)

- cookery (5)

- counterfactualism (1)

- country sports (1)

- cultural propaganda (1)

- culture wars (1)

- Curzon (3)

- Daniel Defoe (2)

- Denmark (1)

- detective fiction (31)

- detectives (19)

- diaries (7)

- dictionaries (1)

- diplomacy (2)

- Disraeli (12)

- documents (1)

- Dorothy L. Sayers (5)

- Dorothy Sayers (5)

- Dostoyevsky (1)

- Duke of Edinburgh (1)

- Duke of Wellington (14)

- East Germany (1)

- Eastern Question (1)

- economic history (1)

- Economist (2)

- economists (2)

- Edmund Burke (7)

- education (3)

- Edward Heath (2)

- elections (5)

- Eliza Acton (1)

- engineering (3)

- English history (56)

- English literature (34)

- enlightenment (3)

- enterprise (1)

- Eric Ambler (1)

- espionage (2)

- European history (4)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- events (22)

- exhibitions (12)

- Falklands (3)

- fascism (1)

- festivals (2)

- films (13)

- food (7)

- foreign policy (3)

- foreign secretaries (2)

- fourth plinth (1)

- France (1)

- Frederick Burnaby (1)

- French history (3)

- French Revolution (1)

- French wars (1)

- funerals (2)

- gardeners (1)

- gardens (3)

- general (17)

- general history (1)

- Geoffrey Howe (2)

- George Orwell (2)

- Georgians (3)

- German history (3)

- Germany (1)

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (1)

- Gibraltar (2)

- Gladstone (2)

- Gordon Riots (1)

- Great Fire of London (1)

- Great Game (4)

- grievances (1)

- Guildhall Library (1)

- Gunpowder Plot (3)

- H. H. Asquith (1)

- Habsbugs (1)

- Hanoverians (1)

- Harold Macmillan (1)

- Hatfield House (1)

- Hayek (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- historians (38)

- historic portraits (6)

- historical dates (10)

- historical fiction (1)

- historiography (5)

- history (3)

- history of science (2)

- history teaching (8)

- History Today (12)

- history writing (1)

- hoaxes (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- House of Commons (10)

- House of Lords (1)

- Human Rights Act (1)

- Hungary (1)

- Ian Gow (1)

- India (2)

- Intelligence (1)

- IRA (2)

- Irish history (1)

- Isabella Beeton (1)

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1)

- Italy (1)

- Jane Austen (1)

- Jill Paton Walsh (1)

- John Buchan (4)

- John Constable (1)

- John Dickson Carr (1)

- John Wycliffe (1)

- Jonathan Swift (1)

- Josephine Tey (1)

- journalists (2)

- journals (2)

- jubilee (1)

- Judaism (1)

- Jules Verne (1)

- Kenneth Minogue (1)

- Korean War (2)

- Labour government (1)

- Labour Party (1)

- Lady Knightley of Fawsley (2)

- Leeds (1)

- legislation (1)

- Leicester (1)

- libel cases (1)

- Liberal-Democrat History Group (1)

- liberalism (2)

- Liberals (1)

- libraries (6)

- literary criticism (2)

- literary magazines (1)

- literature (7)

- local history (2)

- London (14)

- Londonderry family (1)

- Lord Acton (2)

- Lord Alfred Douglas (1)

- Lord Hailsham (1)

- Lord Leighton (1)

- Lord Randolph Churchill (3)

- Lutyens (1)

- magazines (3)

- Magna Carta (7)

- manuscripts (1)

- maps (9)

- Margaret Thatcher (21)

- media (2)

- memoirs (1)

- memorials (3)

- migration (1)

- military careers (1)

- monarchy (12)

- Munich (1)

- Museum of London (1)

- museums (5)

- music (7)

- musicals (1)

- Muslims (1)

- mythology (1)

- Napoleon (3)

- national emblems (1)

- National Portrait Gallery (2)

- nationalism (1)

- naval battles (3)

- Nazi-Soviet Pact (1)

- Nelson Mandela (1)

- Neville Chamberlain (2)

- newsreels (1)

- Norman conquest (1)

- Norman Tebbit (1)

- obituaries (25)

- Oliver Cromwell (1)

- Open House (1)

- operetta (1)

- Oxford (1)

- Palmerston (1)

- Papacy (1)

- Parliament (3)

- Peter the Great (1)

- philosophers (2)

- photography (3)

- poetry (5)

- poets (6)

- Poland (3)

- political thought (8)

- politicians (4)

- popular literature (3)

- portraits (7)

- posters (1)

- President Eisenhower (1)

- prime ministers (27)

- Primrose League (4)

- Princess Lieven (2)

- prizes (3)

- propaganda (8)

- property (3)

- publishing (2)

- Queen Elizabeth II (5)

- Queen Victoria (1)

- quotations (31)

- Regency (2)

- religion (2)

- Richard III (6)

- Robert Peel (1)

- Roman Britain (3)

- Ronald Reagan (4)

- Royal Academy (1)

- royalty (9)

- Rudyard Kipling (1)

- Russia (10)

- Russian history (2)

- Russian literature (1)

- saints (7)

- Salisbury (6)

- Samuel Johnson (1)

- Samuel Pepys (1)

- satire (1)

- scientists (1)

- Scotland (1)

- sensational fiction (1)

- Shakespeare (16)

- shipping (1)

- Sir Alec Douglas-Home (1)

- Sir Charles Napier (1)

- Sir Harold Nicolson (6)

- Sir Laurence Olivier (1)

- Sir Robert Peel (3)

- Sir William Burrell (1)

- Sir Winston Churchill (17)

- social history (2)

- socialism (2)

- Soviet Union (6)

- Spectator (1)

- sport (1)

- spy thrillers (1)

- St George (1)

- St Paul's Cathedral (1)

- Stain (1)

- Stalin (3)

- Stanhope (1)

- statues (4)

- Stuarts (3)

- suffragettes (3)

- Tate Britain (2)

- terrorism (4)

- theatre (4)

- Theresa May (1)

- thirties (2)

- Tibet (1)

- TLS (1)

- Tocqueville (1)

- Tony Benn (1)

- Tories (1)

- trade (1)

- treaties (1)

- Tudors (2)

- Tuesday Night Blogs (1)

- Turkey (3)

- Turner (2)

- TV dramatization (1)

- twentieth century (2)

- UN (1)

- utopianism (1)

- Versailles Treaty (1)

- veterans (2)

- Victorians (13)

- War of Independence (1)

- Wars of the Roses (1)

- Waterloo (5)

- websites (7)

- welfare (1)

- Whigs (4)

- William III (1)

- William Pitt the Younger (4)

- women (11)

- World War I (20)

- World War II (54)

- WWII (1)

- Xenophon (1)

Counters

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(89)

-

▼

April

(21)

- Wot, no comments?

- Illustrations

- That special edition

- Change of Speaker for Tuesday's Meeting

- On the other hand, historical apologies are not in...

- Apologies ....

- Modern detective stories

- The first battle of the American Revolution

- Past wisdom - 3

- The Tory lexicographer

- Wellington dances the flamenco

- Beginnings of the Union Flag

- Brunel's birthday

- The English language as a political tool

- Past wisdom - 2

- Conservative History Group Website Launched

- It really had to happen

- Whatever happened to them?

- Hmmm

- More Burkeana

- Past wisdom - 1

-

▼

April

(21)