In the meantime, Tory Historian has been reading various books, including Amanda Vickery's fascinating account of a number of Georgian families and their womenfolk in Lancashire. Her study is based on the ladies' diaries and letters, giving the reader a strong feeling of entering those lives.

"The Gentleman's Daughter" refutes the accepted historical argument that women of the middle class lost various freedoms and occupations in the eighteenth century and shows their lives in their full and active reality.

A couple of quotations from the introductory chapter set the theme:

What follows then is a study in seemliness; a reconstruction of penalties and possibilities of lives lived within the bounds of propriety. Yet, as will emerge, even the bounds of propriety were wider than historians have been apt to admitPresumably that means that Keira Knightley will not be playing any of them in a bad film. Something to be thankful for.

....

It is hard to imagine them [those gentlemen's daughters, wives, sisters and mothers] ever smiling on the likes of a feminist writer such as Mary Wollstonecraft, a mannish lesbian as Anne Lister or a fashionable adulteress such as Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire.

In the meantime, a happy Christmas to all readers of this blog.

Over on The New Culture Forum Peter Whittle has a posting about the need to learn dates if one is to understand history at all. Readers of this blog know that Tory Historian is very much in favour of dates and marks as many of them as possible. Without knowing when things happened it is impossible to have anything but the most superficial and gooey idea of historical development.

Mr Whittle’s challenge to his readers is to put together a list of 50 dates that would be essential learning for everyone who wants to know anything about history. (And, really, essential learning for school children in their early teens.) There is no indication whether the dates have to do with British or world history but then, as Tory Historian has been told, Britain’s history is world history. Besides certain dates are so important that, no matter where the events happened, we should all know them.

Tory Historian takes up the challenge and passes it on to this blog’s readers. Here are a few ideas: 55BC – Julius Caesar’s invasion, 1066 – Norman Conquest, 1215 – Magna Carta, 1649 – execution of Charles I, 1688 – Glorious Revolution, 1689 – Bill of Rights, 1707 – Act of Union, 1805 – Trafalgar, 1807 – abolition of slave trade, 1815 – final defeat of Napoleon and Britain’s rise to the rank of undisputed world leader, 1832 – First Reform Act, 1867 – Second Reform Act, 1914–1918 – Great War and the start of decline in European hegemony and British power, 1939-1945 – the process completed, 1973 – Britain becomes part of the EEC (later EC and, even later, EU) thus abandoning the idea of sovereign legislation.

Now for some dates in the world that, nevertheless, affected Britain in various ways: 476 – fall of Rome (this is optional), 1453 – fall of Constantinople, 1492 – Columbus reaches America, 1517 – Luther nails 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, 1618-1648 – Thirty Years’ War ending with the Treaty of Westphalia, 1776 – Declaration of Independence, the natural successor event to the signing of Magna Carta and passing of the Bill of Rights, also the end of the first British Empire, 1789 – French Revolution, 1848 – revolutions across Europe, 1861 – Russian serfs freed, 1861-1865 – American Civil War and American slaves freed, 1871 – Unification of Germany, 1917 – Russian revolutions, 1922 – Ireland becomes independent, 1947 – India and Pakistan become independent (these two events herald the end of the British Empire for better or worse), 1989 – fall of the Berlin Wall, 1991 – end of the Soviet Union.

Others will think of other dates and will, perhaps, disagree with Tory Historian’s list. Let’s hear from those to whom historical dates matter.

There is nothing so mortifying for an editor as to be told after an issue of the relevant journal has come out that there is a major mistake in it, particularly as said editor has not yet had her copies. (Ahem, hint.) The mistake is in not crediting a co-author.

In the latest issue of the Conservative History Journal (available from the Conservative History Group) there is an article about the now almost forgotten but in his day very important Conservative politician, Ernest Marples.

Its author is given as Professor David Dutton, author of numerous books on political history. Nothing wrong with that, except for the fact that somewhere in the transference and editing of articles I lost the name of the co-author, Chris Cooper, Professor Dutton's post-graduate student, who, I am reliably informed, did most of the research. I am covered in shame. Ashes and sackcloth are on order.

I hope Mr Cooper will accept my abject apology.

The book looks most interesting and is clearly a vital text for all true Anglospherists but what caught Tory Historian’s attention immediately were the maps. Maps, as has been pointed out before, are essential to almost any book that involving different countries, battles, movements of people, explorers' journeys and almost anything that makes history really exciting.

How can one not warm to a book that has such choice items as the distribution of Royalist and Parliamentarian supporters in the American colonies during the English Civil War? Or “Ulster in America – 1775”, a map of Scotch-Irish distribution in the 13 colonies? And many others.

This is going to be a joyful reading experience, to be reported on in due course.

To the frequently asked question “why does it keep going wrong in Russia” there is a partial answer in that chapter.

Russian autocracy grew out of the understanding patrimony or votchina. Under the Tatar rule, the various appanage princes had to plead for the right to rule from the Tatar Khan but, once allowed, owned the realm in the same way as they owned their own private possessions and homes. The idea that even the most absolute ruler had limits to his power and that was private property simply did not exist in Russia. [It did develop subsequently but very slowly and imperfectly.]

There were other factors absent. On pp. 16 – 17 Professor Pipes says:

The Muscovite state administration evolved from the administration of the appanage, the principal task of which had been exploitation. The prikazy, Moscow’s principal executive offices, similarly evolved from the administration of the prince’s household.Out of it grew the idea that all in Russia were slaves (kholopy) of the prince, later the tsar. They owed him everything and he owed them nothing. Indeed, any suggestion that they had the right to ask for anything or suggest certain changes in public policy was met with righteous anger as late as the nineteenth century even from the most liberal and reformist of the tsars, Alexander II.

As indicated above, such a mentality had also existed in the early mediaeval Europe – for instance, among the Merovingian kings of France, who also treated their kingdom as property. But there an evolution occurred which superimposed the public on the private and produced a notion of the state as a partnership between rulers and ruled. In Russia such an evolution did not occur because of the absence of the factors that had moulded European political theory and practice, such as the influence of Roman law and Catholic theology, feudalism and the commercial culture of the cities.

Tory Historian has the temerity to add one more detail to Professor Pipes’s succinct analysis. Not only was the Russian Orthodox Church less helpful in the development of a society that was separate from the state, it was positively harmful in its insistence that nothing good could be done on earth, anyway. Therefore, there could be no such thing as a good commonwealth or such a person as a good ruler and the possibility of referring to theological ideas in support of certain rights and privileges was not there.

Tory Historian has the temerity to add one more detail to Professor Pipes’s succinct analysis. Not only was the Russian Orthodox Church less helpful in the development of a society that was separate from the state, it was positively harmful in its insistence that nothing good could be done on earth, anyway. Therefore, there could be no such thing as a good commonwealth or such a person as a good ruler and the possibility of referring to theological ideas in support of certain rights and privileges was not there.One can compare Alexander Pushkin’s “Boris Godunov”, written in conscious imitation of Shakespeare’s histories, and the latter’s two plays about Henry IV. There are many parallels: both rulers came to their thrones by dubious means, having, at the very least, acquiesced in the murder of the rightful king or (in Godunov’s case) heir; both worry about their sons for different reasons; and both find that desired crown heavy to wear.

There the parallels stop. Even, Pushkin, the most westernized of all nineteenth century writer (though he was never allowed to leave Russia), could not encompass the idea of Tsar Boris Godunov attempting to assuage his conscience by good deeds on earth and by ruling well and wisely. Whether Henry IV succeeds in any of these aims is not as important as the fact that he sees the possibility of good deeds on earth and of being a good king (to quote “1066 And All That”).

There the parallels stop. Even, Pushkin, the most westernized of all nineteenth century writer (though he was never allowed to leave Russia), could not encompass the idea of Tsar Boris Godunov attempting to assuage his conscience by good deeds on earth and by ruling well and wisely. Whether Henry IV succeeds in any of these aims is not as important as the fact that he sees the possibility of good deeds on earth and of being a good king (to quote “1066 And All That”).The absence of religious teaching about earthly goodness and achievements had a doleful influence on Russian history.

Part of Tory Historian's reading matter is Alan Ebenstein's biography of Friedrich Hayek, not a Tory, not even a conservative, strictly speaking but one of the greatest and most inspiring thinkers of the twentieth century, inspiring for the right in general.

Almost immediately, TH found an interesting quotation about Hayek's influence on opponents of the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, first published in Time Magazine on April 6, 1972:

Tomas Jezek, who became Czech minister of privatization after the collapse of the communist rule, said that if the "ideologists of socialism would single out the one bookd that ought to be locked up at any price and strictly forbidden, its dissemination and lecture [sic] carrying the most severe punishments, they would surely point to The Road to Serfdom".Clearly, they did not lock the book away securely enough.

Kneller’s portraits are 36 by 24 ins, known as the standard “kit-cat” format.

Among the Club members were Sir Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele, authors of the original Spectator and Tatler essays. In 1712 Steele wrote in the Spectator:

Face-painting is no where so well performed as in England.One cannot but agree as one surveys the astonishing array of portrait painters this country (and despite that Whiggish comment it includes Scotland) has either produced or attracted. Sir Godfrey Kneller was, of course, one of the latter.

Tory Historian is pondering a series of postings about portraits and their importance in English and Scottish history and art history.

As promised, here is the Editorial of the new Conservative History Journal, which is now with the printer so can be considered to be in existence. It outlines plans for the future and our readers might be interested to read it on the blog as well. When the Journal is actually visible in hard copy the table of contents will go up as well.

“The best laid schemes o' mice an' men/Gang aft agley”. So said Robert Burns and, though he was hardly a conservative in the usual sense of the word, one cannot really argue with him. The plan to produce a larger Conservative History Journal than its predecessors has actually come to fruition; the plan to produce it a little earlier in the year did not. On the other hand, this issue will be the perfect Christmas reading for all those who are interested in various aspects of the Conservative Party’s history.

There are articles about such diverse subjects as Conservative suffragists and the possible Jacobite connections of the early Tory leaders; there are studies of the reputations of Neville Chamberlain and Benjamin Disraeli; a new analysis is presented of Enoch Powell’s famous speech and of the now almost forgotten Ernest Marples; above all, there are articles about various aspects of the Thatcher and post-Thatcher years. Something for everyone, is the editorial hope.

A section had to be dropped from the Journal for lack of space. It was my intention to write about recently published books that could be of interest to conservative historians and historians of conservatism as well as people interested in conservative history. These were not going to be full reviews but a paragraph or so about such books as Jean M. Lucas’s book about Conservative Agents, “Between the Thin Blue Lines” or Giles Hunt’s “The Duel” about that infamous encounter between Canning and Castlereagh. My intention was to expand the Journal’s horizon by discussing briefly Richard Pipes’s “Russian Conservatism and Its Critics”. There was no space for this wonderful idea, so it will have to be transferred to the Conservative History Journal blog (http://conservativehistory.blogspot.com/).

The blog has taken up a certain amount of my time and will take up even more as I try to turn it into the pre-eminent site for all those who are interested in conservative history. Admittedly, my definition of conservative history has been rather wide but that has not stopped hits from growing and many interesting comments from being posted on it (as well as some trollish ones that had to be removed). Among other strands in it will be the proposed “Books of interest … to those interested in conservative history. Anyone who has ideas of publications to be included is encouraged to let me know about them.

Let us now turn to future plans. I have said this before in editorials but this time I say it with real feeling: the Journal will improve in its punctuality and, indeed, diversify. The plan for early 2009 is to produce a supplement that concentrates entirely on what is the most exciting recent historical and political idea: the Anglosphere. I am collecting articles of 2,000 – 3,000 words that look at the subject of economic and political developments that are specific to Britain or to the way those ideas have developed in the Anglospheric countries. Of course, if someone wants to write a knowledgeable piece on why the Anglospheric ideas are completely erroneous, they are welcome to do so. I shall be happy to include it.

Later in the year, there will be a Conservative History Journal of the kind we are more used to (though, perhaps, used to is not quite the right expression, given the editor’s shocking dilatoriness) that will once again have articles about the Conservative Party, its politicians, the debates and ideas that could be found in its vicinity. There is no editorial policy on what conservatism means; Tory history and Tory ideas are as welcome as more liberal and libertarian ones. The Conservative Party has been a “broad church” for a long time and conservative history must be equally broad.

Let us not forget that there are conservative ideas and movements in other countries as well. Some of them will be covered in the Anglosphere supplement; others can be written about in the Journal itself. There is a third outlet. Part of the blog, I hope, will be contributions by other people. So far I have received two very different ones, which were posted within hours of being sent to me. One was a review of a play in London, the other an eye-witness account of the recent American elections. Other contributions will be very welcome and I do credit the authors. Longer pieces may then be reprinted in the forthcoming issue of the Journal.

Plenty of ideas for all of us to get going with. The Conservative History Journal in all its manifestations should have a bright future.

I am looking forward to responses and suggestions.

Proofs of the Conservative History Journal have been signed off and gone to the printer. Further news of their progression will be reported. Meanwhile, normal service (and a bit better) will resume on this blog.

The next issue of the Conservative History Journal has been set up in page-proofs and is being proof-read today. Which means it will be out within a week. The joyful news of its actual appearance will be heralded on this blog and bells shall be rung across the country.

The editorial includes a number of plans for the future of the Journal and this blog. Once the Journal is in existence I shall put the Editorial up here as well (together with the table of contents to whet everyone's appetite) for readers to start a discussion about those plans.

In the meantime: rejoice, rejoice.

There are a few anniversaries this week that need to be remembered, apart from Remembrance Day (known as Veterans’ Day in the United States). Keeping with the American theme, let us recall that November 10 saw the US Marine Corps’ 233rd birthday. What can one say but Semper Fi?

Now to a darker anniversary: the night of November 9 – 10, 1938 is known as Kristallnacht. It all started on November 7, when the 19 year old Hershel Freible Grynszpan walked into the German embassy in Paris and shot the diplomat Ernst vom Rahm, whether because he was the one immediately available or, as some theories hold, because he really intended to shoot him. Grynszpan’s own story was that he was protesting the treatment of Jews in Germany, particularly that of his own family.

As all terrorist acts, this, too had the opposite of the intended effect, as the Nazis used vom Rath’s death to unleash an überpogrom against the Jews. During Kristallnacht 92 Jews were murdered, between 25,000 and 30,000 were sent to concentration camps, around 200 synagogues were destroyed as were many thousands of Jewish businesses.

Eventually, this led to one of the great horrors of the twentieth century: the Holocaust.

But it would be good to finish on a happier note. Most of the last century was overshadowed by two terrible wars with very little peace between them and, even more so, two monstrous political ideologies: Nazism and Communism.

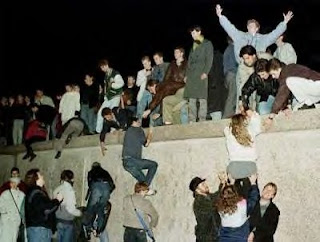

So, let us recall that November 9, 1989 saw the beginning of the end for the second one of these – the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Little needs to be added to that except two pictures: that of the young soldier, Conrad Schumann, leaping to freedom on August 15, 1961, as the Wall was being built and the end of that structure. Let us not forget that it was brought down by the people who, despite being so told by many a left-wing thinker and writer in the West, did not think the German Democratic Republic was a place they wanted to live in.

The 1914 - 1918 war changed the world in a way we have not yet fully managed to deal with. The years before 1939, the Second World War, the subsequent battle with Communism, were all the outcome of that earlier conflict. The wars in the Middle East and the Gulf are also the outcomes of it and of the collapse of the empires that had divided the world. We shall live with that for a long time before we can go to another era, no longer the post 1918 one.

For today we must remember the soldiers who died in that conflict and in the many conflicts since and think of those who are fighting in other wars.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years contemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

All American presidential elections are historic and some turn out to be far more important than anyone had expected. While I find the hype around the newly elected 44th President somewhat ridiculous (he is not the Messiah but another politician with very dubious connections and next to no experience) it is undoubtedly of historic importance. Barack Obama is not black but of mixed race and is not the descendant of slaves though, possibly, through his East African Arab ancestry of slave-traders. But it is, undoubtedly, of great historic importance that the people of the United States elected a President whose father was black. I am, therefore, very pleased to have this analysis of the event from Mark Coalter, a frequent contributor to the Conservative History Journal, who is based in New York at the moment.

The people of America have spoken and they have elected a relative newcomer as their 44th President. A politician who four years ago was sitting in the Illinois legislature, basking in the adulation of election to the US Senate and for being one of the few highlights of the 2004 Democratic Convention, is now the leader of the ‘free world.’ On Tuesday, Barack Obama, with his mantra of Yes We Can!, won a comfortable victory over his Republican opponent. With increased majorities in the House and Senate he has been presented with a tremendous opportunity to facilitate the ‘change we can believe in’, a chance to deliver something durable, which could alter the economic and political landscape, as we know it. Alternatively we may just get another four (or maybe eight) years of much the same, albeit under the auspices of someone more telegenic and aloof than some of his predecessors.

Obama’s election is undoubtedly of historical significance. He is the first African-American to become President (if one discounts the unsubstantiated rumours concerning Warren Harding), although this probably played only a small part in his margin of victory. It is clear that his natural abilities and message of change made him presidential in the eyes of a majority of voters. In the short term, what is perhaps more important for Obama’s presidency, is that unlike Clinton and Bush 43, there are no questions of illegitimacy. Republicans wonder(ed) if Clinton would have won had it not been for Perot’s somewhat eccentric but decisive intervention in a number of traditionally Republican states, such as Colorado, Louisiana, Missouri, and Montana. If Bush had convincingly carried Florida and the popular vote in 2000, instead of the prolonged legal debacle that followed, then would Democrats have been so bitter?

Obama has crossed the 50% threshold and while he did not win a landslide nobody can claim that the election was stolen, at least not at the ballot box. Conservatives can quite correctly object to the heavily slanted media coverage doled out to John McCain (if he even merited a mention) verses the fawning attention provided to Obama. The Democratic candidate’s dramatic u-turn on public financing for his campaign gave Obama a huge financial advantage over McCain allowing him to out-spend the GOP on all fronts. McCain’s principled decision not to feature Rev. Wright in any of his attack ads meant that the most legitimate of Obama’s past association did not become a mainstream campaign issue outside of conservative talk radio and Fox News. The mishandling of the Bill Ayres issue – ‘palling around with terrorists’ instead of focusing on what Ayres and Obama were working towards, i.e. funding programmes designed to promote radical political activity to Chicago high school students – further highlighted the McCain campaign’s inability to land a substantive blow on their opponent. And what of Obama’s connection to the Chicago Democratic machine, a movement that is far from a paragon of ethical activity or political virtue? The Democrat success in imitating and improving upon the much-maligned Karl Rove’s get out the vote operation, so crucial to Bush’s re-election in 2004, also proved key.

Obama has an undeniable mandate for change. How he chooses to use it will be another matter and time will tell in that regard. The economy will be his first major challenge while Iraq and Afghanistan will certainly test commitments made before supporters on the stump. Will Obama reach across the aisle when formulating policy or instead will he take the view that with Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, Republican input is unnecessary? The selection of the combative and (very) partisan Rahm Emanuel as his Chief of Staff would suggest that he has chosen a party loyalist and enforcer as the presidential aide-de-camp as opposed to a conciliator. A sign of things to come?

Nevertheless, let’s see how Obama does. If he acts independently of his base and makes courageous and difficult decisions in the interests of the country as opposed to interest groups and his core supporters, then the new President will have the trappings of greatness. But, if Obama adopts a partisan and leftist agenda and becomes a captive of Congressional Democrats then disappointment will be more widespread than just within conservative circles.

Detective stories are essentially conservative in their outlook and are particularly successful if a settled environment is described. What could be more settled than the environment in which most clerics inhabit, at least, in intention?

So popular clerical detectives are that there is even a website dedicated to the subject. Tory Historian is addicted to detective stories and is reasonably fond of the clerical variety. Too many of them have recently been on the leftish liberal side of the spectrum, which would not matter if all these clerics did not insist on pushing their politics into the face of the reader. Neither they nor their authors appear to understand the essential conservatism of the detective story genre.

A certain amount of liberalism creeps into one of the best series of clerical detection from the nineties, that of D. M. Greenwood’s tales of Deaconess Theodora Braithwaite. Better declare an interest here. Many years ago D. M. Greenwood was known as Miss Greenwood, a classics teacher of terrifying erudition and eccentricity.

While the slight left-leaning is a little unexpected, the clear and beautiful writing and the sharpness with which the shortcomings of the present-day Church of England are dissected are entirely in character with the woman who used a similar scalpel on Tacitus and his characters.

Subsequently Miss Greenwood went back to university to study theology, became what she calls an ecclesiastical civil servant and started writing detective stories. Presumably working for the church at a relatively low level makes it easy to imagine all sorts of nefarious dealings up to and including murder.

Deaconess Braithwaite, a scion of a distinguished Anglican family, a student of classics who turned to theology and who refuses to be priested because she feels the Anglican Church should not break away from all the other ones within Christianity (presumably she means Roman Catholic and the various Orthodox ones as many of the Nonconformist denominations have had women ministers for some time) is an engaging character. So are many of the others who appear in the various novels though, sadly, few more than once. The intrigues and shabbiness of the Church hierarchy are brilliantly described and there are sharp portraits of various people who are attracted to the institution for various reasons.

In addition, Theodora Braithwaite is writing a biography of an eminent (fictitious but so realistic) Victorian Tractarian, Thomas Henry Newcome, who is brought into sharp focus, together with his formidable wife in the book Tory Historian has just finished reading, “Heavenly Vices”.

In other words, this is an entirely admirable series and strongly recommended to all readers. There is just one problem: the plots are terrible. Even Philip Grosset, onlie begetter of the Clerical Detectives site, has to admit this, though he, too, lists Theodora Braithwaite as one of his favourite detectives.

“Heavenly Vices” just about works if one can accept the dubious notion that people will murder in order to preserve the Church of England from yet another highly unpalatable scandal.

However, Tory Historian finds it extremely unlikely that a woman like Deaconess Braithwaite would think in meters rather than feet and yards. Was it D. M. Greenwood herself or some officious editor who described the appearance of a cottage Theodora Braithwaite is approaching:

The Saplings was a solid red brick villa with mock Tudor beams. The front garden, no more than three metres from gate to front door, was laid out with miniature box hedges interspersed with fine gravel.Would Deaconess Braithwaite even know how long three metres were?

On the other hand, there is a wonderful conversation between the Kenyan priest Isaiah Ngaio, to whom Theodora is unfailingly though somewhat condescendingly (even though she would call it understandingly) gracious, and the spoilt, hysterical and self-obsessed son of the late Warden of Gracemount Theological College. Needless to say, the Warden’s death is not what it seems:

Isaiah is pushed into asking the detestable Crispin:

“Whom do you hate?”That passage with the undeniable truth at the heart of it ought to encourage more people to read about Deaconess Theodora Braithwaite.

“Myself, my father.”

“Count your blessings and act out of them.”

“What blessings would those be then?”

Isaiah looked down at this flimsy youth and thought of his own country: “You ate well last night. You can read and write. You can journey from one end of this country to the other without men with Kalashnikovs demanding your deference. You have no right to your discontent, no right to your hatred. Your only proper emotion is gratitude.”

“You don’t understand.”

“There is One who does. Seek His path and healing will surely follow.”

But Crispin had been raised by and among people who considered the development of self in all its florescent glory was the true end of man.

The next meeting of the Conservative History Group will take place on November 24. The speaker will be Andrew Roberts who will talk about his new book, "Masters and Commanders", which sounds extremely good. I have heard Roberts talk about it but have not got round to reading it. One more on the list.

The meeting will start at 6.30 and will take place in the Wilson Room in Portcullis House. Please remember that security might take longer than you expect.

In the post a new book by Professor Jeremy Black, an historian who wears the label "conservative" as a badge of honour (as, indeed, he should). This one is a slight departure for him but one that many historians make from time to time. One of them was Andrew Roberts, the dedicatee of the book.

Black's book is entitled "What If? - Counterfactualism and the problem of history". Tory Historian has no doubt that this is a suitably learned discourse and is looking forward to reading it. (The book is published by the Social Affairs Unit.)

The subject of counterfactualism is dear to Tory Historian's heart. Not the sort of fantasy and wishful thinking that some people indulge in but a real counterfactual history is very useful. It is, after all, the only way that historians can conduct anything resembling a control experiment.

One removes one factor from a historic event, a factor that might or might not have been there, and examines all the others anew. Would the same result have ensued if certain possibilities had been different? Quite often the answer is yes. There would have been no significant changes in historical development.

Every now and then, on the other hand, it is possible to see probable differences, thus defining more accurately the importance of particular historic strands.

The greatest of all is on October 21, Battle of Trafalgar. A great battle, a great victory and a great tragedy with the death of the Admiral, Lord Nelson. And on the left readers can see a chart of how the battle lines were drawn up.

October 22 was a bleak day in 1962 as President Kennedy, comprehensively outwitted by Nikita Khrushchev, announced that there were Soviet missiles on Cuba, pointing at the United States. The most frightening period of the Cold War when the two protagonists faced each other without any intermediaries between them began.

October 23 is too often remembered as the beginning of the Hungarian revolution of 1956 but let us not forget that it was also the date of the Battle of Edgehill in 1642. This was the first major battle of the Civil War with Charles I and Prince Rupert leading the Royalists and the Earl of Essex the Parliamentarians. Who won? Well, that’s a difficult one. It was a draw though if Charles had moved faster he would have been the real winner as the road to London was open to him. That is what Prince Rupert advocated. Instead, Charles proceeded with caution (most unlike him in political terms) and Essex reached London first.

Moving right along there, October 24, 1537 marks the death of Henry VIII’s third Queen, Jane Seymour, the one who produced the coveted heir. Presumably, had she survived puerperal fever, she would have kept her head as the mother of the heir. Or maybe not.

October 25, 1854 saw the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War and the less said about it the better. In any case, Tennyson said it all before and in much better metre. Well, actually, the day saw the battle itself, including the Charge of the Heavy Brigade, which was successful and is, therefore, rarely remembered by anyone except tedious people like Tory Historian. Incidentally, Captain Nolan, the man who seems to have been responsible for the messy lack of communication between various commanders, was not an upper class twit, but a career officer from a less than well-off army family. He had trained and served in the professional Continental armies and wrote books on the cavalry.

October 26, 1863 is a most important date as it marks the formation of the English Football Association, otherwise known simply as the FA. The first meeting was held in the Freemasons’ Tavern in Great Queen Street, in London.

October 27, 1914 was the day the poet Dylan Thomas was born.

October 28, 1831 was when Michael Faraday demonstrated the dynamo. This can be considered the beginning of electro-magnetism.

Just two more dates and we shall complete this rather busy period. October 30, 1925 saw the transmission of the first television moving image by John Logie Baird. I don’t think we can blame him for what TV has become since that day. And finally, a very important date for modern history: on October 31, 1517 Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. The beginning of the Protestant reformation.

Well, one cat at the moment. One cat at a time. Tory Historian decided to spend some time in the British Museum this afternoon but the place was just a little packed. Saturday in half term may not be the best time for museum visits. And when, may we ask, will those long-promised European galleries be open?

Well, one cat at the moment. One cat at a time. Tory Historian decided to spend some time in the British Museum this afternoon but the place was just a little packed. Saturday in half term may not be the best time for museum visits. And when, may we ask, will those long-promised European galleries be open?

A quick trip round some of the favourites and some mooching in the Enlightenment Gallery - full of surprises as ever - and a photograph of the Cat Bastet, otherwise known as the Gayer-Anderson cat after the man who donated her to the museum.

Recently some scientific work on the cat has shown that Colonel Gayer-Anderson probably mended a crack in the body and inserted a piece of steel into the head to keep the statue together, painting it green afterwards. A great deal more was established about the material from which the cat was made. And it has been known for a long time that the cat dates from a fairly late period: after 600 BC.

No amount of scientific work can deal with the extraordinary personality the statue possesses. Tory Historian is rather proud of the photograph. So much so that coffee and cake in the nearby London Review Bookshop was called for afterwards.

History books need maps, travellers’ accounts need maps, biographies often need maps, even detective stories are better if there is a map or a chart with X marking the spot where the body was found.

So why are there no proper maps in Niall Ferguson’s “Empire”? There are nice pictures and lots of graphs – line graphs, block graphs, even pie-charts possibly, as Professor Ferguson is an economic historian but no proper big maps that show journeys, discoveries, battles, acquisitions? The odd small map of the British Caribbean or of the global telegraph network or a schematized, uninteresting chart of British Africa do not make up for the fact that one cannot follow Dr Livingstone’s various journeys, not even the really important ones.

What is the point of talking about Livingstone’s serious misunderstanding of what the Zambezi was really like if one cannot turn a page and chart the progress of his first and second expeditions?

How can one grasp what really happened during the American War of Independence without a map of the 13 colonies with battle lines carefully drawn?

Maps, we need more maps. Here is one for starters.

At the heart of the book is the horticultural rivalry for Queen Elizabeth’s favour between William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, whose chief gardener was the great herbalist John Gerard (c.1545 – 1612) and Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester. Gerard supervised Burleigh’s main garden in Theobalds Palace in Hertfordshire against which Leicester pitted his Italianate garden at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire where he held a 19-day festivity for the Queen in 1575.

This is what Ms Martyn says about the great Queen herself:

Elizabeth inherited her interest in herbalism from her father, who had his own collection of herbal potions. She was fiercely opposed to physic (more akin to what we would now call conventional medicine), refusing to take it even when close to death. This gave her something in common with her people, most of whom relied on herbal remedies, if only because English physicians charged the highest fees in Europe.A few interesting points in that. Firstly, the reference to Henry VIII’s herbal potions is intriguing though one must remember that a great deal of all medicine was based on that in the sixteenth century with many theories about humours abounding. Indeed, further down Ms Martyn explains that the arguments between physicians and poor women who sold those potions were usually about money – the physicians wanted a monopoly.

Which brings one to the most entertaining point: English physicians charged the highest fee in Europe. Was that for the same herbal potions or for bleeding patients or for providing them with leeches? In the end, it all comes down to money rather than medical arguments.

Tory Historian possesses a number of old cookery books, alas mostly in reprinted or edited versions and they all have sections for all kinds of herbal and other potions and remedies. One of the most interesting “illnesses” is not really that but something called “green sickness” from which girls and young women suffered, especially towards the end of winter. The remedy was a drink laced with iron filings, created within the household, not bothering any physician. In other words, anaemia in young women and teenage girls was a widely recognized phenomenon and the remedy for it was also known.

Moving along historically, this is what Professor Ferguson has to say at the end of his long chapter, entitled "Why Britain?", a question he does not precisely reply to. "Why", in Tory Historian's opinion is not the same as "how". But the "how" is fascinating.

In 1615 the British Isles had been an economically unremarakbale, politically fractious and strategially second-class entity. Two hundred years later Great Britain has acquired the largest empire the world had ever seen, encompassing forty-three colonies in five continents. The title of Patrick Colquhoun's Treatise on the Wealth, Power and Resources of the British Empire in Every Quarter of the Globe (1814) said it all. They had robbed the Spaniards, copied the Dutch, beaten the French and plundered the Indians. Now they ruled supreme.One could simply assume that late entrants are likely to profit by the mistakes of earlier players as well as their exhaustion, but that would hardly be an adequate explanation for it all.

Was all this done "in a fit of absence of mind"? Plainly not. From the reign of Elizabeth I onwards, there had been a sustained campaign to take over the empires of others.

Yet commerce and conquest by themselves would not have sufficed to achieve this, no matter what the strength of British financial and naval power. There had also to be colonization.

The robbing, beating and plundering was done by all, though, perhaps, the copying was a peculiarly sensible British innovation. In other words, Tory Historian is greatly looking forward to an answer to the question "why"?

The robbing, beating and plundering was done by all, though, perhaps, the copying was a peculiarly sensible British innovation. In other words, Tory Historian is greatly looking forward to an answer to the question "why"?This blog has not been forgotten. It's just that Tory Historian has been living in a series of rushes. There will be postings in a few hours.

The TV series is being touted as a gold standard against which the new film is being found wanted. No critic, so far as Tory Historian can make out, has made a reference to the book “Brideshead Revisited”, though Christopher Hitchins had a long article in the Guardian. In it he discussed, with great erudition, Waugh’s language, the Catholic aspects of the novel (Hitchens finds that a tad distasteful) and the significance of the Great War. He clearly finds the film very inferior and damns the TV series with faint praise:

The directors Charles Sturridge and Michael Lindsay-Hogg achieved their 1981 success by gorgeous photography, of course, and also by generally inspired casting. The locations, plainly, required little or no embellishment. And the music was suitably ... well, evocative. But most of all, they were faithful to Evelyn Waugh's beautiful dialogue and cadence, both in set-piece scenes and in sequences of languorous voice-over in Oxford and Venice and - perhaps decisively - in the opening passage, where the melancholic Captain Charles Ryder hears the almost healing word "Brideshead" spoken again: "a name that was so familiar to me, a conjuror's name of such magic power, that, at its ancient sound, the phantoms of those haunted late years began to take flight".In fact they were not as faithful to Evelyn Waugh’s undoubtedly beautiful dialogue as all that, allowing John Mortimer, the scriptwriter a good deal of freedom to write his own additions. Mortimer is a good writer but he is not in the Waugh class and has very different ways of using words and approaching themes. Quite often his additions were very clunky.

But there was gorgeous photography, evocative music, beautiful buidlings and scenery, wonderful clothes. In fact, the whole series concentrated on heritage nostalgia, making the plot and characterization too slow and too sentimental for the book.

The novel itself, underrated when it first appeared and dismissed as one of Waugh’s snobbish works, is now regarded as one of the great novels of the twentieth century, both as a description (not a very flattering one, which is another thing the dramatizers often miss) of a particular world and as a difficult moral fable. The dramatizations make it into a nostalgic romance in much the same way as recent dramatizations of Jane Austen’s novels turned those into Mills and Boon type romances.

Waugh, himself, would not have been surprised at this development. In a way, he predicted it through one of the characters in “Brideshead Revisited”. Anthony Blanche, played by the excellent Nickolas Grace in the TV dramatization but not emphasised nearly enough and, if the reviews are anything to judge by, downgraded quite severely in the film, is one of the most interesting personages in the book.

He does not appear much but he is the one who perceives matters more clearly than anyone else. Fittingly, the first time we see him, at Sebastian’s luncheon party, he declaims lines from the “Waste Land”:

He does not appear much but he is the one who perceives matters more clearly than anyone else. Fittingly, the first time we see him, at Sebastian’s luncheon party, he declaims lines from the “Waste Land”: And I, Tiresias, have foresuffered allIn his notes to the poem Eliot says:

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

Tiresias, although a mere spectator and not indeed a ‘character’, is yet the most important personage in the poem, uniting all the rest. … What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem.Anthony Blanche, in some ways, is the Tiresias of the novel, knowing and observing, and this includes the sexual conundrum: is he male or female, or might he be said to be both? He is, however, clear-sighted in his own, deliberatly absurd fashion, about the Flyte family and about art. Waugh always denied that Blanche was based on the aesthete and art historian Harold Acton, preferring to point to Brian Howard, a less well known and considerably less interesting personality, as the original.

Whatever the truth of that is, it is clear that Anthony Blanche is a true aesthete in the sense of understanding and appreciating art and artistic endeavour. He appears about four times in the book. The first time at Sebastian’s luncheon, where he makes a strong impression on Charles Ryder and recites the Tiresias lines to undergraduates who are off to do a spot of rowing.

Subsequently, he takes Charles out to dinner during which he tells the story of him being debagged by some rowdy undergraduates in excruciating and, probably, inaccurate detail. But, above all, he warns Charles against Sebastian, the Flyte family and, more generally, against “creamy English charm” that suffocates and destroys everything it touches, particularly artistic talent.

Charles is a little afraid of Anthony and disturbed by the remarkably accurate prediction of his own and Sebastian’s behaviour. Sebastian, on the other hand, rather unwisely dismisses Anthony as being a silly show-off.

There is another brief appearance when Blanche tells Charles that he had seen Sebastian in his travels; the latter has become effectively an alcoholic and has acquired a disreputable German companion, whom Charles later meets and dislikes.

The fourth and final appearance of Anthony Blanche is at a crucial moment in Charles Ryder’s life. Having become successful as a painter of country mansions, Charles finds that his talent is stultifying so he goes off to Central America to paint in the jungle. On the way back he meets Julia Flyte, now Mottram, and they begin their affair.

In London Charles exhibits his pictures, which the visitors to the private view find “barbaric” and “unhealthy”. Anthony turns up and carefully examines the paintings then takes Charles off to a louche place we would now call a gay bar and delivers his verdict. Charles Ryder the artist has been destroyed. His new paintings are nothing but “charm again, my dear, simple creamy English charm, playing tigers”.

His final comment before he dismisses Charles is quite chilling but appropriate to the dramatizations:

I took you out to dinner to warn you of charm. I warned you expressly and in great detail about the Flyte family. Charm is the great English blight. It does not exist outside these damp islands. It spots and kills anything it touches. It kills love, it kills art; I greatly fear, my dear Charles, it has killed you.The rest of the novel unfolds, mostly at Brideshead, around Charles’s affair with Julia and the rest of the surviving Flyte family to the dramatic high point of Lord Marchmain’s death and the consequent collapse of what was not perhaps the great love that Charles had imagined. There is no more mention of his work as an artist, though, presumably, he continues to paint.

The TV dramatization and, by all accounts, the film even more so prove Anthony Blanche’s point. That creamy charm has spotted and killed the great novel that Evelyn Waugh had written, at any rate for most people, and, it would seem, most critics. For many of us, though, the novel will remain and will overcome the blight. Well, one can hope.

English and Scottish explorers arrived in the New World a little late and could not find what they wanted – large amounts of gold that was enriching the King of Spain. Therefore, they acquired riches by raiding the Spanish and Portuguese ships and settlements, causing periodic small wars in Central and Southern America as well as the various islands.

On the other hand, it was a cheap way of finding new lands and of fighting the Spanish who had become a direct threat to England under Elizabeth. Send the ships out and let them earn their own keep. If they returned with gold and pearls a percentage went to the Queen. If not, they could take their chances.

The privateer (or pirate) Professor Ferguson spends some time on is the infamous Captain Henry Morgan who tried to terrorize Spanish settlements in present-day Cuba, Panama and a few other places. As Professor Ferguson points out:

The scale of such operations should not be exaggerated. Often the vessels involved were little more than rowing boats; the biggest ship Morgan had at his disposal in 1668 was no more than fifty feet long and had just eight guns. At most, they were disruptive to Spanish commerce. Yet they made him a rich man.The real point of interest is what Captain Morgan did with his money. He claimed to be a “gentleman’s son of good quality” from Monmouthshire. This was disputed by some and a Frenchman, Exquemlin, who had probably taken part in some of the raids, wrote an account of Captain Morgan’s career, in which he implied that the man had arrived in the Caribbean as an indentured servant. The book was published first in Dutch, then in English.

This, Captain Morgan felt, was an insult to him, though he did not mind the descriptions of what he and his men did during those raids. When “The History of the Bucaniers” came out in England, the good captain sued the publisher and was awarded £200. Subsequent editions of the book had to be amended. It just goes to show that libel tourism has a longer history than any of us knew.

Well, what did he do with his ill-gotten gains?

He invested in Jamaican rreal estate, acquiring 836 acres of land in the Rio Minho valley (Morgan’s Valley today). Later, he added 4,000 acres in the parish of St Elizabeth. The point about this land was that it was ideal for growing sugar cane. And this provides the key to a more general change in the nature of British overseas expansion. The Empire had begun with the stealing of gold; it progressed with the cultivation of sugar.The sugar duties brought the Crown substantial earnings and Jamaica became a prime economic asset that had to be defended. Fortifications were built to protect the harbour at Port Royal.

Significantly, the construction work at Port Royal was supervised by none other than Henry Morgan – now Sir Henry. Just a few years after his pirate raid on Gran Grenada, Morgan was now not merely a substantial planter, but also Vice-Admiral, Commandant of the Port Royal Regiment, Judge of the Admiralty Court, Justice of the peace and even Acting Governor of Jamaica.And so the greatest Empire the world has ever known began in this rather ramshackle fashion.

Once a licensed pirate, the freelance was now being employed to govern a colony. Admittedly, Morgan lost all his official posts in 1681, after making “repeated divers extravagant expressions …. in his wine. But this was an honourable retirement. When he died in August 1688 the ships in Port Royal harbour took turns to fire twenty-two gun salutes.

It is a little unfortunate that so many of today’s historians and writers are prepared to go along with that. Robert Self’s excellent biography that came out in 2006 does not seem to have challenged those widespread assumptions.

Let us be reasonable. In the autumn of 1938 neither Britain nor France was in a position to go to war with Germany. France was not in a position to do so even in 1939 – 40 and Britain did not exactly perform well in the first months of the war. Those who maintain that Chamberlain should have resisted Hitler, if necessary by declaring war, do not give any clear ideas as to what the country could have done, particularly as at that stage the Empire and the Dominions would not have given their support.

So, in reality, Chamberlain ensured that Britain did not lose the war against Germany and was much better equipped to fight when the inevitable time for it came. Tory Historian has to disagree with the great Andrew Roberts, who wrote in his article in the Daily Telegraph that

Although the Chamberlain Government had allowed Czechoslovakia to be abandoned and dismembered by the Munich agreement, it had (unwittingly, since Chamberlain had trusted Hitler) bought Britain and her Commonwealth nearly a year which they used to rearm.Rearmament had been going on for some time and Chamberlain was not so trusting of Hitler as to abandon it. Indeed, he remained proud even after his resignation from the premiership right up to his death soon after it that he had helped to make Britain more capable of fighting the war and, certainly, defending herself. There was nothing unwitting about that. Avoiding or, more likely, postponing war seemed like a good idea.

Two questions are of particular interest. One is how is it that Munich has become such a word of shame when, for example, Yalta, a far greater betrayal of allies who had fought with Britain and the United States, is usually cited as an example of statesmanly conduct on the part of the two Western leaders. (The role of Soviet agents like Alger Hiss, in the background, is rarely mentioned.)

People who urge appeasement at every possible opportunity still fulminate when the word Munich is mentioned and weep crocodile tears over the unfortunate Czechs, without once explaining what exactly Britain could have done in practical terms in 1938.

The other rarely asked question is what would have happened if the Czechoslovak armed forces had resisted the German invasion of Sudetenland in 1938. After all, whatever one may think about French or British obligations, surely the obligations of President Beneš’s government to defend their country were far greater. Yet they refused to give the order, preferring to blame the western powers for the greatest betrayal history had ever known.

Could they have fought with any possibility of success? Most assuredly. In their 1997 biography of Edvard Beneš the Czech historians Zbynĕk Zeman and Antonín Klimek wrote:

The prospect of going to war with Germany came as no surprise to the Czechoslovak government of the 1930s. Prague had, in fact, been preparing for war seriously for years: by some estimates, over half of all government spending from 1936 to 1938 was for military purposes. Much of this went towards the construction of an elaborate system of bunkers and other defences in the Sudetenland, the border region shared with Germany.Furthermore, it has been estimated that there were 200 fortified artillery batteries and 7,000 bunkers along the border. The Czechoslovak army was the third largest in Europe and a few days before the Munich Agreement 1.5 million people had been mobilized. The German mobilization of August 1938 resulted in 2 million people. In other words, this was not a titchy, badly prepared little force facing up to the might of Germany (at that time somewhat overestimated by Britain and France).

The Wikipedia entry on the occupation of Czechoslovakia says, for once reasonably accurately:

Czechoslovakia was a major manufacturer of machine guns, tanks, and artillery, and a highly modernized army. Many of these factories continued to produce Czech designs until factories were converted for German designs. Czechoslovakia also had other major manufacturing concerns. Entire steel and chemical factories were moved from Czechoslovakia and reassembled in Linz, Austria which, incidentally, remains a heavily industrialized sector of the country.Given that the less well armed, Polish army that was relying on a smaller industrial base and was also attacked by the Soviet army simultaneously with the German one managed to inflict a great deal of damage on the Wehrmacht in 1939, the Czechoslovak forces might well have tied up the German for a considerable length of time, making Hitler’s claim to the inevitability of victory seem hollow. Yet the order to fight never came and the mobilized men went home.

Undoubtedly, this caused anguish in the way Czechs viewed their multinational country and their government. The myth of the supreme treachery of Munich may well have buried some of those feelings but they do surface from time to time.

In the meantime, it might be a good idea for us to rethink our conventional wisdom.

Writing about propaganda, for instance, he rightly compares Soviet films about the Civil War in which the evil Whites are vanquished by the heroic Reds after a great deal of fighting and with many losses with Hollywood films where similar scenarios are played out on the opposite side. However, the films with heroic Reds, in Orwell's opinion, are more useful in the long run than the ones with heroic Whites. Admittedly, this was written before he recognized fully the evil of Communism but he remained a man of the left.

The essay that Tory Historian concentrated on this time was "Notes on Nationalism", written in 1945 and an excellent analysis of the intelligentsia and its political attitudes before and during the Second World War.

The whole piece is worth reading but here are two quotations that remain relevant:

It is curious to reflect that out of all "experts" of all the schools, there was not a single one who was able to foresee so likely an event as the Russo-German pact of 1939. [It is worth adding that Orwell always referred to Russia when he meant the Soviet Union and, also, that, as he himself acknowledges in a footnote, some conservative writers, such as Peter Drucker, did realize that there would be some kind of an alliance.] And when the news of the Pact broke, the most wildly divergent explanations of it were given, and predictions were made which were falsified almost immediately, being based in nearly every case not on a study of probabilities but on a desire to make the U.S.S.R. seem good or bad, strong or weak.The other quotation Tory Historian found particularly apt comes from the same essay in the discussion of political Catholicism, the precursor of Communism as the intelligentsia's nationalism of choice.

Political or military commentators, like astrologers, can survive almost any mistake, because their more devoted followers do not look to them for an appraisal of the facts but for the stimulation of nationalistitc loyalties.

Writing about G. K. Chesterton's later work Orwell points out that it consisted almost entirely of loud statements that demonstrated "beyond possibility of mistake the superiority of the Catholic over the Protestant or the pagan".

This was not enough:

But Chesterton was not content to think of his superiority as merely intellectual or spiritual: it had to be translated into terms of national prestige and military power, which entailed an ignorant idealization of the Lating countries, especially France. Chesterton had not lived long in France, and his picture of it - as a land of Catholic peasants incessantly singing the Marseillaise over glasses of red wine - had about as much relation to reality as Chu Chin Chow has to everyday life in Baghdad.One can argue about the literary merits of Chesterton's poems (Orwell is falling into the trap he so clearly describes of dismissing the literary merits of a work with which he disagrees) and, undoubtedly, Tennyson's can be used for pacifist arguments but the main argument remains as valid as ever.

And with this went not only an enormous overestimation of French military power (both before and after 1914 - 1918 he maintained that France, by itself, was stronger than Germany), but a silly and vulager glorification of the actual process of war. Chesterton's battle poems, such as Lepanto or The Ballad of Saint Barbara, make The Charge of the Light Brigade read like a pacifist tract:

they are perhas the most tawdry bits of bombast to be found in our language.

The interesting thing is that had the romantic rubbish which he habitually wrote about France and the French army been written by somebody else about Britain and the British army, he would have been the first to jeer.

In home politics he was a little Englander, a true hater of jiongoism and imperialism, and according to his lights a true friend of democracy. Yet when he looked outwards into the international field, he could forsake his principles without even noticing that he was doing so.

Thus, his almost mysical belief in the virtues of democracy did not prevent him from admiring Mussolini. Mussolini had destroyed the reperesentative government and the freedom of the Press for which Chesterton had struggled so hard at home, but Mussolini was an Italian and had made Italy strong, and that settled the matter.

There was nothing new about this curious juxtaposition of ideas. The crusading left-wing journalist W. T. Stead was also one of the strongest supporters of Alexander III's authoritarian regime in Russia. Nor has anything much changed. We know about the left-wing support for every kind of oppressive and totalitarian regime in the twentieth and twenty-first century. But less has been said about people, on the left and on the right, who while arguing for democracy and national sovereignty as far as Britain is concerned, also support certain Russian and Balkan leaders whose views and behaviour are the very antithesis of that. Chesterton's spirit hovers over them all.

As the drawings are of writers like Kipling, Hardy and Jerome K. Jerome, of the Manager of the Times newspaper, Charles Moberley Bell and of various actor-managers, idleness is not quite the word that immediately springs to mind.

The most interesting of the portraits is of Henry Algernon George Percy, Earl Percy (1871 – 1909), a man so well-known in his time, that in 1908 when the drawing was published in The Bystander, the title of it was “A Future Tory Leader”. A year later he was dead and how many people have even heard of him today?

Ever curious about past grandees, Tory Historian looked around, found a very inadequate piece on Wikipedia, which did, however, refer to the intriguing story of death being the result of a duel, and turned to the Oxford Dictionary of Biography and the Dictionary of National Biography.

True or otherwise, the official story of Earl Percy catching a chill in Paris and dying of it does irresistibly remind one of the unfortunate end of Ernest Worthing, Jack Worthing's mythical and wicked younger brother, in Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest”. In actual fact, Earl Percy was, if anything, more like the main character of “An Ideal Husband” without the unfortunate secret in the past.

Henry Percy was the eldest son of the 7th Duke of Northumberland but died too young to inherit the title. He seems to have done extraordinarily well at school and university, winning the 1892 Newdigate Prize for English Verse at Oxford. The slightly unusual subject he chose was St Francis of Assisi.

In 1895 he won a by-election at South Kensington and continued to represent that constituency until his death. Another important event of that year was his first visit to Turkey and the Near East. He went back in 1897 and published “Notes of a Diary in Asiatic Turkey” the following year.

His 1899 visit produced “The Highlands of Asiatic Turkey” in 1901. Earl Percy became known as an expert on the Near East and was made Parliamentary Under-Secretary for India in 1902 but really came into his own and Under-Secretary to Lord Lansdowne, the Foreign Secretary, in 1903. He specialized in matters to do with Turkey and often took an independent line from his superior and the government in general.

For instance, Earl Percy promoted the idea of an Anglo-German alliance that would stabilize Turkey and stem growing Russian influence. One can’t help wondering how the twentieth century would have developed if that idea had been followed instead of the later, liberal Entente Cordiale of 1904 and Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907.

Earl Percy was accused of having “perhaps excessive sympathy for Turkey”, an unpopular point of view by the time of the early twentieth century, though it might have been better received by Disraeli. He also showed himself to be rather concerned with the political position of Muslims in India as the discussions on possible reforms progressed in 1906 – 1907.

Another of his important political achievements was the renewal and strengthening of the Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1905.

One can quite see why in an age when foreign policy mattered a great deal to a government, a man like Earl Percy would have been seen as a potential leader. An untimely death meant not just the end of his career (which would be obvious) but his disappearance from the history of the Conservative Party. One cannot help wanting to know about more “lost leaders” like Earl Percy.

More from Diane Urquhart's book on the formidable Londonderry ladies. This quote is singularly relevant to certain developments in the American presidential election, where the "second-wave feminists" have found themselves on the back foot:

There is no question that the marchionesses formed part of a small coterie of political confidantes and hosteses who worked by distinctly personal means in high society to promote their family, direct careers and impact change while their marriage and widowhood would respectively facilitate and impede their political influence.Actually, that "second-wave feminism" borrowed the idea from the Marxists.

Indeed, the idea of the personal being political, brought to the public's attention by the second-wave feminism of 1960s America, can be applied to a different place and a different time: in this instance to nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain and Ireland.

The glamour of the Duchess of Devonshire has eclipsed a very important historical fact. She was not the only lady to have become involved in politics long before female suffrage had become a political fact. Nor were the Whigs the only ones to have powerful and influential political hostesses.

Tory Historian is reading Diane Urquhart's "The Ladies of Londonderry", a history of that powerful family through the distaff side. The book follows the story for 150 years, from 1800 to 1959, by which time the role of the political hostess had diminished though had not disappeared completely.

With women entering politics directly and, as it turned out, ready to rise to the very top, back-stage management seemed to be a little less important. Further reports of the book will follow.

The Rosenbergs were really spies? Well, colour me surprised, as they say on the other side of the Pond. It seems that Morton Sobell, who was convicted of espionage with the notorious pair, has now admitted that yes, indeed, he and Julius Rosenberg with the help of his wife Ethel, spied for the Soviet Union.

As it happens, the Venona documents and more recent finds in the KGB archives before they were closed to the public again have shown some time ago that there was not the slightest doubt on the subject. But, as the Rosenbergs have been a cause célébre for the left during the last fifty odd years, it is all a surprise. Whatever next? Alger Hiss was really a GRU agent? Surely not!

Well, naturally, my first port of call was John Barnes, who is a mine of information about the Conservative Party and its history. He knew, of course, and directed me to the books that could give me more information. Quite a story it is, too, as I put it together, using Andrew Roberts’s biography of Lord Salisbury, Robert Rhodes James’s biography of Lord Randolph Churchill and Richard Shannon’s “The Age of Salisbury”. Oh and a quick look at R. J. Q. Adams’s “Balfour”.

The story is quite fascinating and puts to pay the notion that somehow politics was a much more gentlemanly affair when it was run by “gentlemen”. The Salisbury/Northcote fight with Churchill was anything but gentlemanly. In the end, Churchill lost not because he was a nicer person but because, seduced by apparent party adulation, he could not envisage anybody outmanoeuvring him as Salisbury did. Lord Randolph Churchill, it seems, believed that he was indispensable – the most dangerous delusion any politician can have.

The National Union of Conservative Associations was founded in 1867 and held its first meeting in the Freemasons’ Tavern in London on November 12 of that year. In 1868 they went to Birmingham and there were 7 people in attendance. By 1869, in Liverpool there were 36 delegates. And so it would have continued but for the disastrous Conservative defeat in 1880. As Robert Rhodes James puts it in his biography of Lord Randolph:

It is a monotonous feature of English politics that the defeated party in an election blames its organization for the débâcle. The Conservatives in 1880 were no exception to this rule.So they formed a Central Committee under Lord Beaconsfield’s auspices and this organization was put in charge of direction and management of party affairs, as well as the disbursement of party funds. Clearly, this did not please the National Union, who considered themselves to be the representatives of the real Conservative Party.

The real difficulty (and I hope people who know far more about Conservative Party politics will wade in here) is to work out what motivated Lord Randolph Churchill. He presented himself as the man who spoke for Tory democracy, for the working class members of the party, for all the various constituent groups against the “Carlton Club” elite, who wanted to run things the old way. (By the way, the forthcoming issue of the Conservative History Journal will have an article on the Carlton Club by the eminent expert Alistair Cooke.)

The idea of Lord Randolph as a representative of the working man or of anything resembling real democracy is slightly odd and one cannot help thinking that he viewed the National Union as a convenient ladder for his own advancement to the leadership, something that he most definitely desired, his rebellious attitude notwithstanding.

In 1882 the National Union began to articulate complaints about its inferior status in the party’s structure and in July 1883 Churchill was elected to its Council with the help of the Chairman’s casting vote. The Chairman was Lord Percy. There were several resignations, including that of Sir Stafford Northcote and Henry de Worms.

We come to the great Birmingham Conference of the National Union, the 17th, held in October 1883, when Lord Randolph Churchill, with the aid of fellow “Fourth Party” member, John Gorst, made his first serious attempt to take over the party.

The leadership sent Viscount Cranbrook to deal with the attack and, according to Richard Shannon, he did it rather well. Responding to Churchill’s fiery speech that accused the Central Committee of being inward looking and hostile to “working men” in the party as well as of financial mismanagement, Cranbrook raised the question of whom the National Union really represented – the constituencies or the affiliated organizations. He also denied any financial mismanagement and, it seems, that Churchill and his allies never managed to prove that. On the other hand, they did point out that the National Union had no funds to speak of.

In his diary Cranbrook referred to “Randolph Churchill’s Birmingham intrigues”, which is what it looked like to the Conservative leadership. The membership was more divided in its opinion. (In parenthesis one may render thanks for the fact that so many British politicians, however busy they may have been, kept consistent and detailed diaries. This is a fascinating subject all by itself that needs to be written about more.)

In December of that year Churchill became Chairman of the National Union’s Organisation Committee, though the method used was rather dubious, as it ought to have been Lord Percy and this may well have alienated some potential supporters.

Lord Randolph’s exemplar was Joseph Chamberlain’s National Liberal Foundation, which was prospering at this time to the point of taking over the party. Coincidentally, of course, Birmingham was Chamberlain’s power base.

Subsequent manoeuvrings, snipings and open warfare between Salisbury with his allies and Churchill with his allies did culminate in some sort of a compromise, under which the latter went through various ministerial appointments, once there was a Conservative government, ending with the Chancellorship.

In December 1886 Churchill over-reached himself and using a disagreement over proposed army and navy spending, offered his resignation, probably not anticipating its acceptance. Famously, he had forgotten about Goschen, who took over as Chancellor, though he was a Liberal Unionist.

That is not how it was supposed to develop from that Annual Conference in Birmingham in 1883.

Links

Followers

Labels

- 1922 Committee (1)

- abolition of slave trade (1)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- academics (2)

- Adam Smith (2)

- advertising (1)

- Agatha Christie (4)

- American history (33)

- ancient history (4)

- Anglo-Boer Wars (1)

- Anglo-Dutch wars (1)

- Anglo-French Entente (1)

- Anglo-Russian Convention (2)

- Anglosphere (19)

- anniversaries (175)

- Anthony Price (1)

- archaelogy (8)

- architecture (8)

- archives (3)

- Argentina (1)

- Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams (1)

- art (14)

- Arthur Ransome (1)

- arts funding (1)

- Attlee (2)

- Australia (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Baroness Park of Monmouth (1)

- battles (11)

- BBC (5)

- Beatrice Hastings (1)

- Bible (3)

- Bill of Rights (1)

- biography (21)

- birthdays (11)

- blogs (10)

- book reviews (8)

- books (78)

- bred and circuses (1)

- British Empire (7)

- British history (1)

- British Library (9)

- British Museum (4)

- buildings (1)

- businesses (1)

- calendars (1)

- Canada (2)

- Canning (1)

- Castlereagh (2)

- cats (1)

- censorship (1)

- Charles Dickens (3)

- Charles I (1)

- Chesterton (1)

- CHG meetings (9)

- children's books (2)

- China (2)

- Chips Channon (4)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (1)

- cities (1)

- City of London (2)

- Civil War (6)

- coalitions (2)

- coffee (1)

- coffee-houses (1)

- Commonwealth (1)

- Communism (15)

- compensations (1)

- Conan Doyle (5)

- conservatism (24)

- Conservative Government (1)

- Conservative historians (4)

- Conservative History Group (10)

- Conservative History Journal (23)

- Conservative Party (25)

- Conservative Party Archives (1)

- Conservative politicians (22)

- Conservative suffragists (5)

- constitution (1)

- cookery (5)

- counterfactualism (1)

- country sports (1)

- cultural propaganda (1)

- culture wars (1)

- Curzon (3)

- Daniel Defoe (2)

- Denmark (1)

- detective fiction (31)

- detectives (19)

- diaries (7)

- dictionaries (1)

- diplomacy (2)

- Disraeli (12)

- documents (1)

- Dorothy L. Sayers (5)

- Dorothy Sayers (5)

- Dostoyevsky (1)

- Duke of Edinburgh (1)

- Duke of Wellington (14)

- East Germany (1)

- Eastern Question (1)

- economic history (1)

- Economist (2)

- economists (2)

- Edmund Burke (7)

- education (3)

- Edward Heath (2)

- elections (5)

- Eliza Acton (1)

- engineering (3)

- English history (56)

- English literature (34)

- enlightenment (3)

- enterprise (1)

- Eric Ambler (1)

- espionage (2)

- European history (4)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- events (22)

- exhibitions (12)

- Falklands (3)

- fascism (1)

- festivals (2)

- films (13)

- food (7)

- foreign policy (3)

- foreign secretaries (2)

- fourth plinth (1)

- France (1)

- Frederick Burnaby (1)

- French history (3)

- French Revolution (1)

- French wars (1)

- funerals (2)

- gardeners (1)

- gardens (3)

- general (17)

- general history (1)

- Geoffrey Howe (2)

- George Orwell (2)

- Georgians (3)

- German history (3)

- Germany (1)

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (1)

- Gibraltar (2)

- Gladstone (2)

- Gordon Riots (1)

- Great Fire of London (1)

- Great Game (4)

- grievances (1)

- Guildhall Library (1)

- Gunpowder Plot (3)

- H. H. Asquith (1)

- Habsbugs (1)

- Hanoverians (1)

- Harold Macmillan (1)

- Hatfield House (1)

- Hayek (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- historians (38)

- historic portraits (6)

- historical dates (10)

- historical fiction (1)

- historiography (5)

- history (3)

- history of science (2)

- history teaching (8)

- History Today (12)

- history writing (1)

- hoaxes (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- House of Commons (10)

- House of Lords (1)

- Human Rights Act (1)

- Hungary (1)

- Ian Gow (1)

- India (2)

- Intelligence (1)

- IRA (2)

- Irish history (1)

- Isabella Beeton (1)

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1)

- Italy (1)

- Jane Austen (1)

- Jill Paton Walsh (1)

- John Buchan (4)

- John Constable (1)

- John Dickson Carr (1)

- John Wycliffe (1)

- Jonathan Swift (1)

- Josephine Tey (1)