March, on the whole, is not a good time for tyrants and oppressive regimes. It is the month of uprisings and revolutions, regardless of what happens to them afterwards. March 15, for instance saw the start of the Hungarian revolution of 1848.

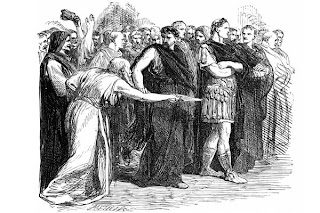

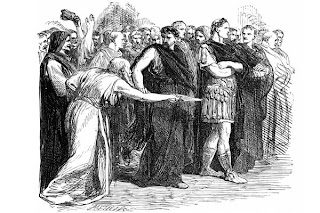

Most famously, of course, it is the Ides of March, the day on which Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of conspirators, some of whom, at least, were intent on preserving the Roman republic....