Tory Historian happens to be what is vulgarly described as a sucker for newsreels of the past. What a joy it is, therefore, to find two videos on the History Today blog, one of people celebrating in the streets in 1918 on hearing that the war is finally over and the other is a longish piece of various dignitaries arriving for the Versailles Conference. There is even a sequence of the documents being signed. One wonders where the Pathé News cameraman is standing as the pictures always seem to be above and behind everybody else.

Or PMQs as they are known not so affectionately. Tory Historian's Blog mentioned the fiftieth anniversary of this tradition before. Nevertheless, a section on the Parliamentary website seemed like a good opportunity to revive the subject. There are many interesting links in the piece, but it is somewhat unfortunate that it is so badly written and edited.

There is, for example a reference to a Parliamentary Breifing Note. Really, that rule ought to be known by people who work in the House of Commons. And what does the first sentence mean?

"The 24 October 2011 marks the 50th anniversary of Prime Minister's Question Time as a permanent parliamentary event." The 24 October 2011? Dear me.

Still, there are many gems of interest to people who find parliamentary history and traditions interesting. Go to it with a will, say I.

In Federalist 51, James Madison (or it might have been Alexander Hamilton) wrote:

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.Tory Historian has always though that it is the practical and rational attitude of the Founding Fathers to the people (or the People, if one prefers) which is so attractive about their ideas. Here were no utopian idealists who saw what they wanted to see but hard-headed individuals who knew that there was no such thing as an ideal politician or an ideal voter.

Jeremy Black, a conservative historian who is probably a member of the Conservative Party as well, writes in History Today about the grievance industry.

Grievances are a characteristic of post-Cold War history, as various ‘liberated’ peoples have adopted historical claims in the service of their political goals. The end of the Cold War discredited Marxism as an official creed and lessened its influence as a basis for analysis, resulting in a major shift away from the understanding of society linked at an international level to the expression, revival or rise of national grievances, notably within Eastern Europe.Using the past to justify actions in the present is a very old game, indeed. As old as history itself. It is possible that the number and frequency of grievances aired in the public sphere has multiplied since the end of the Cold War but, on the whole, I think not.

Grievances provide an easy way to mobilise identity and expound policy; and the use of grievance in this fashion by one party encourages its use by another. The copy-cat nature of public history has become very apparent, as in rival Chinese and Japanese accounts such as those inspired by recent territorial disputes in the East China Sea. Grievance becomes a means both to interrogate the past and to deploy the past to justify current actions.

Public grievances seem to multiply in direct relation to the compensation available, either in financial or political terms. Sometimes that compensation is simply the demand that certain, otherwise unpalatable, actions be condoned as the Chinese government expects and receives from numerous commentators.

Sometimes it is a question of simple acknowledgement as, I think and hope, with the Armenians and the 1915 massacre, though the insistence on that insidious word "genocide" makes one wonder. Frequently, however, it is a demand for more direct compensation with money or land. Why I do not think this is a particularly post-Cold War phenomenon is because there is one set of horrors for which precious little compensation has been paid out in any shape or form, and that is horrors imposed by Communist regimes.

Tory Historian finds a great deal of C. S. Lewis's writing entertaining and instructive. A copy of Mere Christianity, the published version of Lewis's extremely successful wartime broadcasts on religion and morality has produced many gems.

Tory Historian finds a great deal of C. S. Lewis's writing entertaining and instructive. A copy of Mere Christianity, the published version of Lewis's extremely successful wartime broadcasts on religion and morality has produced many gems.

Lewis says that some people have suggested to him that moral judgement that we all, according to him, have is, perhaps, just an instinct like other instincts. Not so, replies he. Instincts are like the notes in music but it is moral judgement that tells us how to play them. Left to themselves, instincts will not guide us and they never do. Even the best instincts can steer us in the wrong direction.

The most dangerous thing you can do is to take any one impulse of your own nature and set it up as the thing you ought to follow at all costs. There is not one of these that will not make us into devils if we set it up as an absolute guide. You might think love of humanity in general was safe, but it is not. If you leave out justice you will find yourself breaking agreements and faking evidence in trials 'for the sake of humanity', and become in the end a cruel and treacherous man.This is a phenomenon we have all become very familiar.

News comes of two incredibly principled poets, who, one assumes, fight like anything for their various fees and royalties, withdrawing from the T. S. Eliot poetry prize, because ... oh fie ... it is now sponsored by nvestment management firm Aurum Funds. Oh, oh, oh. Smelling salts someone, please.

The Poetry Book Society negotiated the three-year sponsorship deal with Aurum earlier this year. The deal followed the withdrawal of its Arts Council funding – a move protested by over 100 poets including Carol Ann Duffy and Simon Armitage.TH is a little confused. It would appear that when "such institutions" give money voluntarily to sponsor a poetry competition, that is wrong and evil but if money is extracted from them by the state in the form of taxes and then handed over in the form of subsidy, that is good.

Kinsella told the Bookseller that he "fully" understood why the poetry organisation had looked elsewhere for funding, "given the horrendous way they were treated, but as an anticapitalist in full-on form, that is my position".

"Hedge funds are at the very pointy end of capitalism, if I can put it that way," he added.

Oswald, who pulled her collection Memorial from the prize on Tuesday, believes that "poetry should be questioning not endorsing such institutions".

All one can say is that it is a good thing that people like Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo did not think along those lines. Neither did T. S. Eliot, as it happens. He spent a good part of his life working in a bank and then running a publishing firm that made profits.

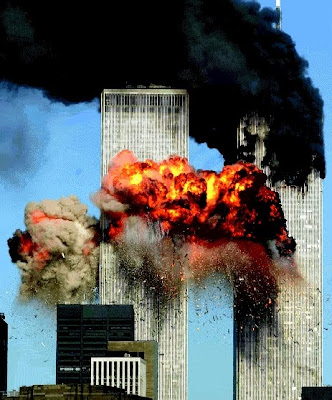

USS Shaw:

USS Arizona:

Pictures of Pearl Harbor devastation, courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command

Tory Historian has mentioned before (here and here, for instance) that detective stories are the most conservative of literary genres. And here is an article I wrote on it last week for Taki's Magazine.

Consider what happens in a detective story, even a modern one that purports to have a leftward (or “enlightened”) leaning: A crime, probably murder, is committed, possibly followed by similar crimes. The world is turned upside-down as a result. Together with the detective, we cannot rest until the perpetrators are discovered and brought to justice. The perpetrator is at the very least prevented from repeating the crime. Human life is sacrosanct. Murder is wrong, no matter how you look at it. It is the ultimate crime. It destroys nature’s balance, which can be restored only by the culprit’s discovery and his or her punishment. In a century that saw the casual elimination of millions of people, this highly moral attitude became and remained attractive to many people. This has continued into the new century, which has not started off too well.Do read the article. The more hits it gets the better it is for yours truly.

Have not yet read Robin Harris's The Conservatives - A History. In the meantime here is John O'Sullivan's excellent review that makes one want to rush out and get the book immediately.

November 28 is a double anniversary. In 1919 the first woman MP actually to take up her seat in the House of Commons was elected. Nancy Astor contested the seat of Plymouth South after her husband had succeeded to the title and went up to the House of Lords. She beat the Liberal candidate, Isaac Foot and, as the left-wing Spartacus Educational reminds us, her victory annoyed many professed feminists as she was definitely not one of them and a Conservative to boot. Also an American but she had made her home in Britain.

There have been previous postings about Thanksgiving and its significance both for the United States and the Anglosphere in general. (here, here and here)

There have been previous postings about Thanksgiving and its significance both for the United States and the Anglosphere in general. (here, here and here)

This time Tory Historian brings to the notice of all the First Thanksgiving Proclamation - June 20. 1676. This was not, as it happens, the first celebration of Thanksgiving, which took place in 1621, to celebrate a bountiful harvest. Interestingly, it was not till 1942 that the exact timing of Thanksgiving - last Thursday in November - was fixed by Federal law.

A generation of children knows virtually nothing about British history and leaves school "woefully under-nourished", Education Secretary Michael Gove warned today.Even if they happen to have heard of those particular facts they rarely have an idea of which of them came first as history is taught, if at all, in bits and unrelated pieces. Time, surely, to take the problem seriously. Perhaps, my idea of setting up a school or college that taught only history to all those who are willing to pay should be thought about more seriously.

Even university students studying the subject are failing to recall basic historical facts, he said. Mr Gove said that around half of young people were unaware that Nelson led the British to victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, or that the Romans built Hadrian's Wall.

As it happens there were two events of some importance on that day, both deaths, though the immediate reporting for many days, weeks, months and, it sometimes feels, even years, has concentrated on one: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

As it happens there were two events of some importance on that day, both deaths, though the immediate reporting for many days, weeks, months and, it sometimes feels, even years, has concentrated on one: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Tory Historian is a great supporter of the London Library, which is described by Wikipedia, probably accurately, as "the world's largest independent lending library, and the UK's leading literary institution".

Tory Historian is a great supporter of the London Library, which is described by Wikipedia, probably accurately, as "the world's largest independent lending library, and the UK's leading literary institution".

1841: As The London Library was founded in 1841 we've been taking a look at other significant literary events that took place in the same year and as well as being busy founding The London Library, Thomas Carlyle published On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History. Another early supporter of the Library, Charles Dickens, published The Old Curiosity Shop. In the same year Punch magazine was founded in London and Horace Greeley began publication of the New York Tribune.Hmmm.

All one can add is that the library's history collection is magnificent but nothing can beat the Reading Room and its extraordinarily comfortable armchairs. Warning: do not sink into them if you do not wish to fall asleep.

And why not? Pubs, in their many manifestations (yes, inns and public houses have changed over the centuries), are an intrinsic part of British history, different in different parts of the country.

The Duke of Wellington, one of Tory Historian's heroes was a considerably more important politician (as well as an overwhelmingly important military commander) than TH had been led to believe at school. He was also a man who was admired unstintingly by all except the Radicals (and even they inclined to some admiration).

The Duke of Wellington, one of Tory Historian's heroes was a considerably more important politician (as well as an overwhelmingly important military commander) than TH had been led to believe at school. He was also a man who was admired unstintingly by all except the Radicals (and even they inclined to some admiration).

Sadly, none of that is true and Tory Historian needs to rethink everything read in those textbooks and heard in the lessons. It would appear that the Duke did have a great deal of political aptitude and a very good understanding of European affairs as well as a great fear (like most military men) of another European war. He was central to British politics for many years after Waterloo and went on serving as a public servant almost until the day of his death. Many of his political judgements were considerably more intelligent and penetrating than those of people on the other side who were the heroes of those long-ago school lessons.His funeral on November 18, 1852 "caused as much of a stir in the mass media of 1852 as did Sir Winston Churchill's in the middle of the twentieth century". This link will lead to a list of references and illustrations in contemporary Illustrated London News. Here is a brief account of the funeral - it was the last heraldic state funeral held in Britain.

Viscount Castlereagh has never been given his full due by his own countrymen, argues Professor Bew in this article. There is, he says, an attempt to make him sound entirely relevant to the modern age but that is wrong, too.

Viscount Castlereagh has never been given his full due by his own countrymen, argues Professor Bew in this article. There is, he says, an attempt to make him sound entirely relevant to the modern age but that is wrong, too.

The truth is that Castlereagh can be understood only as a product of the time in which he operated, rather than as a bearer of any timeless insights. Nonetheless, as his descendant, the Marchioness of Londonderry, argued in 1904, he was not ‘the old-fashioned Tory that ignorant opinion supposes’. Often presented as the enemy of Enlightenment, he travelled widely in Europe, read a broad range of literature and eschewed the anti-Catholicism of many of his peers in England and Ireland. He was convinced that the only approach that government could take towards religion was one of toleration and that each man had the right to make his peace with God on his own terms. True, he was an enemy of political reform, but this was because of the dangers of mob politics which he saw first-hand in Paris during the French Revolution and Ireland during the rebellion of 1798.Professor Bew's own book will undoubtedly put the matter right. Well, we hope so, anyway.

Thus Castlereagh’s mind was conservative and enlightened at the same time – and no less the one for being the other. ‘I think those people who are acquainted with me,’ he told the House of Commons in 1817, ‘will do me justice to believe that I never had a cruel or unkind heart.’

Tory Historian was delighted to read this item in the Daily Telegraph a few days ago.

RJ Balson and Sons, a butchers based in Bridport, Dorset, boasts an astonishing history that is almost 500 years old.The business has expanded and is thriving.

Experts have traced the businesses roots back through 25 generations to when founder John Balson opened a stall in the town's market on South Street in 1535.

Since then dozens of family members have worked as butchers in the market town, passing their skills down the generations.

And 476 years later, the shop remains a thriving business and has been named Britain's oldest family run retailer.

It has been in its present location since 1880, not far from its orginal location.One can but hope that the account books have been preserved somewhere for all the centuries. What a mine of fascinating information they would be.

According to the Institute for Family Business, this makes it the oldest continuously trading family business in Britain.

The firm sells its produce, including 20 varieties of sausages such as els, boar and ostrich,l all over the world, with a large customer base in America.

It also sells exotic fare such as pheasants and guinea fowl but has remained close to its traditional roots.

I am planning to have a series of articles about detective fiction on this site as it is, in my opinion, the most conservative of all genres, a proposition that I shall argue at a later date. As ever, this is also an appeal to readers: if there is anybody out there who is thinking of writing anything about a detective story or thriller writer or about the genre or any part of it in general, do please send it to me and I shall put it up on this site and publicize it as well as I can.

I am planning to have a series of articles about detective fiction on this site as it is, in my opinion, the most conservative of all genres, a proposition that I shall argue at a later date. As ever, this is also an appeal to readers: if there is anybody out there who is thinking of writing anything about a detective story or thriller writer or about the genre or any part of it in general, do please send it to me and I shall put it up on this site and publicize it as well as I can.

To start with I should like to quote P. D. James, possibly the best known and most highly regarded writer of detective fiction in Britain and other countries at present. A couple of years ago she wrote a slim volume (unlike her most recent novels, which are not just fat but obese) about the genre as a whole. I intend to write about this book as it is of interest to anyone who is interested in the genre and in conservative ideas. For the moment, however, I should like to quote two paragraphs that appear towards the end and sum up the subject:

And here in the detective story we have a problem at the heart of the novel, and one which is solved, not by luck or divine intervention, but by human ingenuity, human intelligence and human courage. It confirms our hope that, despite some evidence to the contrary, we live in a beneficent and moral universe in which problems can be solved by rational means and peace and order restored from communal or persona disruption and chaos.One can but hope. We are sadly in need of some sort of a Golden Age.

And if it is true, as the evidence suggests, that the detective story flourishes best in the most difficult of times, we may well be at the beginning of a new Golden Age.

Tucked away in one of the rooms on the second floor of the National Portrait Gallery there is a small exhibition. It takes up no more than half a not very large room and consists of four portraits, four engravings and another, separate engraving of the artist, William Dobson, who was born in 1611 and died in 1646, soon after the collapse of the Royalist cause and his return to London.

Tucked away in one of the rooms on the second floor of the National Portrait Gallery there is a small exhibition. It takes up no more than half a not very large room and consists of four portraits, four engravings and another, separate engraving of the artist, William Dobson, who was born in 1611 and died in 1646, soon after the collapse of the Royalist cause and his return to London.

He had stayed with the King in Oxford as long as he could, painting portraits of Royalists, officers and politicians, and, back in London was imprisoned briefly for debts and died soon after his release, at the age of 36 and in poverty. It is fair to say that Royalist money was running out by the mid-forties but one wonders exactly how concerned either the King or the Prince of Wales were concerned with the fate of loyal servants.

There is a serious attempt being made to celebrate this talented English portraitist with various exhibitions and art-trails across the country. One can applaud that and we certainly hope that readers of this site will take note of whatever may be happening near them (if they happen to be in England).

His biography shows many gaps. Did he learn from Van Dyck directly or merely was influenced by the man's gemius? It is fair to say that Dobson's portraits eschew Van Dyck's elegance, which is, presumably, the result of conditions. Dobson was not painting the golden court of Charles I but the Royalistss besieged in Oxford, running out of money, support and, in the artist's case, painting supplies.

There is some evidence that after his return to London and release from prison he tried to revive his career. His name, as the brief biography points out, appears in the records of the London painters' guild, which would suggest that either his Royalist links were not known or, more likely, overlooked by the guild.

Another attempt by Royalist artists of various kind to earn money was to publish engravings. Several of Dobson's portraits were engraved by William Faithorne, who had fought in the Royalist army, had been captured at the end of Basing House siege and was actually in prison when he was making the engravements, published by Thomas Rowlett. As the notes for this part of the exhibition say,this may well have been an attempt for Royalists to earn some money after the defeat of the King's army.

Rowlett closed his publishing after the King's execution and the business was sold to Peter Stent who used some of the old plates, including one of Endymion Porter, which he reproduced as the Parliamentarian Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex.

The exhibition may be small but the portraits and engravings on display are very fine (the best one may well be that of Richard Neville, above) and there is a great deal of fascinating information.

Tory Historian was thrilled to read yesterday in the Evening Standard that a previously unknown portrait by Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez has been found among various paintings by a little known British artist, Matthew Shepperson, whose own work, about to be auctioned is unlikely to bring in more than a few hundred pounds apiece.

Tory Historian was thrilled to read yesterday in the Evening Standard that a previously unknown portrait by Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez has been found among various paintings by a little known British artist, Matthew Shepperson, whose own work, about to be auctioned is unlikely to bring in more than a few hundred pounds apiece.

Portrait of a gentleman, bust-length, in a black tunic and white collar, was previously owned by 19th Century British artist Matthew Shepperson.The portrait will be auctioned in December by Bonhams and is expected to fetch £3 million. As a corollary, there may well be a renewed interest in Matthew Shepperson's work as well, an example of which, the 1828 portrait of John Childs is here.

It was discovered after a number of artworks by Shepperson were consigned for sale last year.

Further examination and an x-ray confirmed the work to be Velazquez.

The painting first came to attention when the current owner - a descendant of Shepperson - brought the works to Bonhams auction house in Oxford. In-house experts noticed the stylistic similarities to works by the Spanish master Velazquez.

It led to extensive research which was confirmed by Dr Peter Cherry - professor of art history at the University of Dublin and one of the world's foremost authorities on Velazquez - and then by the Prado Museum in Madrid, which carried out the technical analysis.

Nigel Fletcher, Director of the Conservative History Group and new editor of the Conservative History Journal has an interesting piece about Prime Minister's Questions at the age of 50 (more or less). On the whole, he thinks the experiment has worked as it places the British Prime Minister, uniquely, in a position where he (or she, let us not forget) is bombarded by questions from the Opposition and sometimes his (her) own backbenchers. The fact that many of the questions are put-up jobs remains a minor detail.

Some themes that emerge are familiar: PMQs has become a circus; more heat than light; Punch and Judy… and so on. But there is also the positive view – that there are few if any other countries where the chief executive has to come to Parliament weekly to be questioned by their critics. Some would say this fact on its own – whatever the quality of the questions and answers- is a profound statement of representative democracy. I tend to agree.Hmm. That ignores the fact that the Prime Minister is not the Head of State and, also, that the American system is one of true separation of powers, perhaps a more useful check on Executive power than a weekly question session.

We shouldn’t underestimate the symbolism of this political endurance sport. However grand and ‘Presidential’ a Prime Minister may aspire to be, the weekly bear-pit of the Commons reminds them from where they draw their authority. The US President may be obstructed and defeated by Congress, but on the rare occasions he turns up to address them he is treated with the full courtesy, bordering on reverence, due to a Head of State. The fact that the British Prime Minister can have the leader of the main opposition party literally shouting in his face may not be pretty, but it is important.

Following the publication of the highly praised biography of Sir Nikolaus Pevsner by Susie Harries, the Victorian Society will be holding a one-day seminar on October 29 about Pevsner and Victorian architecture. All details, including fees, place and time to be found through the link above. (Susie Harries's blog about Pevsner is here and very interesting it looks, too.)

Tim Stanley, the Contrarian, has a good piece in History Today, which deals with the ridiculous issue of David Starkey's comment about the lootings of this summer, that

Tim Stanley, the Contrarian, has a good piece in History Today, which deals with the ridiculous issue of David Starkey's comment about the lootings of this summer, that

a particular sort of nihilistic gangster culture has become the fashion. And black and white, boy and girl, operate in this language together'.The ridiculousness does not come from the rightness or wrongness of that comment. There are good historical reasons for disagreeing with Mr Starkey; it comes from the curious reaction from various members of the pontificating classes, including, apparently and shamefully, historians.

Some people argued that the BBC should stop classing Starkey as a historian. Over a hundred academics signed an open letter that 'the BBC and other broadcasters think carefully before they next invite Starkey to comment as a historian on matters for which his historical training and record of teaching, research and publication have ill-fitted him to speak … We would ask that he is no longer allowed to bring our profession into disrepute by being introduced as "the historian, David Starkey".'The man is unquestionably and historian though other historians may disagree with what he says. The idea that historians should not be allowed to comment and be described as such on matters that are outside their obvious competence is plainly ridiculous.

Tory Historian is reading Edward Glaeser's Triumph of the City, an unashamed and sometimes slightly too gung-ho praise of the idea and reality of the city in history. Not that TH disagrees with that; it's just that the language is sometimes immoderately joyful, a mode that is alien to TH. At an early stage, Glaeser says this:

I find studying cities so engrossing because they pose fascinating, important, and often troubling questions. Why do the richest and the poorest people in the world so often live cheek by jowl? How do once-mighty cities fall into disrepair? Why do some stage dramatic comebacks? Why do so many artisitic movement arise so quickly in particular cities at particular moments? Why do so many smart people enact so many foolish urban policies?The last of those, TH thinks, begs the question of whether those people who enact foolish urban policies really are all that smart.

Actually it was yesterday but Tory Historian was busy with other non-cyber matters. A belated happy birthday to Baroness Thatcher, three-times Conservative Prime Minister and still an inspiration to many across the world, for yesterday.

Actually it was yesterday but Tory Historian was busy with other non-cyber matters. A belated happy birthday to Baroness Thatcher, three-times Conservative Prime Minister and still an inspiration to many across the world, for yesterday.

Tory Historian is something of a Wyndham Lewis fan, considering him to be one of the most underrated artists and writers of the twentieth century. Leafing through the 1954 collection of essays, first published in The Listener, entitled The Demon of Progress in the Arts, TH found a very fine piece, called The Glamour of the Extreme and was particularly taken by the second paragraph:

Tory Historian is something of a Wyndham Lewis fan, considering him to be one of the most underrated artists and writers of the twentieth century. Leafing through the 1954 collection of essays, first published in The Listener, entitled The Demon of Progress in the Arts, TH found a very fine piece, called The Glamour of the Extreme and was particularly taken by the second paragraph:

I have a friend who is a natural bourgeois. He was the son of a minor Eminence. At the university, during the fellow-travelling decade, he got in the habit of talking big and bloody about social revolution. He was not intelligent or mentally mature enough to udnerstand the guillotine and the firing squad; he had not even read Karl Marx. But for the rest of his life, and he is now over fifty, he has remained a sort of undergraduate communistWell, thought Tory Historian, more than half a century later we still know people like that. Far too many of them.

Children's literature, if it is to be successful with children has to tread a fine line between conservatism (which is what most children are most of the time) and subtle rebelliousness (which is what their parents are most of the time). The William Brown stories, written by a true-blue Conservative, Richmal Crompton, manage to tread that line very successfully, though there is the odd exception, as Derek Turner discusses in this highly entertaining and knowledgeable article on the writer and her work. The story of the Outlaws becoming the "Nasties" and deciding to attack Mr Isaacs's sweet shop is rather unpleasant but has a happy ending, but for many modern readers the unpleasantness negates the ending. It is an odd story, for it shows that Richmal Crompton was fully aware as early as 1934 the sheer nastiness of the Nazi regime, yet decided to make something light-hearted of it. This is not quite the same as William's on-off liking for the Communists as there are no details of Stalinist policy involved.

Fought 440 years ago on October 7, 1571 it is also the cause of a great poem by one of the most conservative poets of the twentieth century, G. K. Chesterton, published 100 years ago, in 1911 (well, not to the day).

The National Portrait Gallery is a wonderful institution and is of great value to anyone who finds history and its players interesting. Its special exhibitions, on the other hand, are variable from that point of view and are too often merely collections of various glamour photographs of recent stars.

The First Actresses presents a vivid spectacle of femininity, fashion and theatricality in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain.Well, really, who can resist that?

Taking centre stage are the intriguing and notorious female performers of the period whose lives outside of the theatre ranged from royal mistresses to admired writers and businesswomen. The exhibition reveals the many ways in which these early celebrities used portraiture to enhance their reputations, deflect scandal and create their professional identities.

For various reasons to do with an article to be completed Tory Historian has been reading a fascinating book by Alison K. Smith, called Recipes for Russia, subtitled Food and Nationhood under the Tsars. It deals partly with attempts to discuss and reform agriculture in Russia in the nineteenth century and partly with the late development of cookery books from the end of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century, analyzing the links between agriculture or food and national identity.

For various reasons to do with an article to be completed Tory Historian has been reading a fascinating book by Alison K. Smith, called Recipes for Russia, subtitled Food and Nationhood under the Tsars. It deals partly with attempts to discuss and reform agriculture in Russia in the nineteenth century and partly with the late development of cookery books from the end of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century, analyzing the links between agriculture or food and national identity.

particularly the art of translating - became the source of a new image of the Russian nation as an imperializing and assimilating one. Incorporating foreign literary works into the Russian canon helped suggest the power of the Russian state, and its ability to borrow from abroad without losing its sense of self.She then draws a parallel with writing about food:

Something rather similar developed on the tables of Russia's elite. By choosing to eat foods labeled [sic] Russian, even the westernized elite could still think of themselves as tied to the land. Or, alternatively, the persistence of Russian foods even among those whose dress, carriages, and even language had shifted enormously displays a raeal connection between Russians of different social estates. Whether mere façade, the mixture of foreign and native foods struck many foreign visitors as deeply disturbing.For Russian authors, though, she adds, this was a source of pride as native Russian and foreign influences were combined to create a Russian cuisine beyond the old-fashioned, rather crude Russian cooking.

Every now and then one can find some truly useful information on Wikipedia. This list of the world's Independence Days, sent to Tory Historian by a well-wisher, is one of them. It has all the national flags as well, which is an added bonus.

As usual, Tory Historian will produce the odd blog or two on the subject but it is worth reminding readers in or near London of this wonderful event. If I may make a suggestion, try to buy the whole booklet of what is open in some friendly bookshop (too late to do so on line) rather than try to figure out what to do and where to go from the website. Happy hunting!

Tory Historian has never quite understood why the bien pensants otherwise known as people who never read detective stories, considering them to be inferior, but like pontificating consider Agatha Christie's novels to be particularly unrealistic. It is true that criminals are not always brought to justice (and they are not always in her novels either) but that is the premiss of that most conservative of genres, the detective story.

Tory Historian has never quite understood why the bien pensants otherwise known as people who never read detective stories, considering them to be inferior, but like pontificating consider Agatha Christie's novels to be particularly unrealistic. It is true that criminals are not always brought to justice (and they are not always in her novels either) but that is the premiss of that most conservative of genres, the detective story.

It is also true that she is often slapdash and cavalier about certain details, in particular dates, time spans, ages. All of that annoys Tory Historian as readers can imagine. This is so different from the silly but precise novels by Georgette Heyer. But when it comes to descriptions of life and social mores she is far more realistic and accurate than her contemporaries Ngaio Marsh or Margery Allingham.

The accusations that she wrote about large country houses and aristocratic families and parties is completely untrue. Her milieu was the middle class, her people almost entirely professionals, lawyers, doctors, clergymen, the occasional businessman, maybe members of the squierarchy like Colonel Bantry. That is why she managed to write well about changes in social life. The village in A Murder is Announced is very different from the village of Murder in the Vicarage. The people who may have had a couple of servants before the Second World War have maybe a foreign refugee, a cleaning woman or an au pair after it. The large households either disappear or are reinvented to suit some Hollywood star. All very realistic.

People who consider Raymond Chandler to be more realistic have, one assumes, read neither author but have dimly heard the expression about the man in the mean streets. Murder happens in mean streets and in well-appointed homes or flats shared by three middle-class girls. Are those convoluted, incomprehensible plots of Chandler's, full of wisecracking people truly realistic? Hardly.

So we come to Tory Historian's reading matter of the day and that is John Curran's Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks. Some interesting stuff about the way Christie developed her plots though after a while one loses interest in the minutiae of literary invention. There are also two stories that have never been published before, one called The Incident of the Dog's Ball, which, Mr Curran works out, was probably written in 1933 but never offered to Christie's agent. Readers of her novels will instantly recall one of her best, Dumb Witness, published in 1937. Mr Curran thinks the story was withheld because the author decided almost immediately to turn it into a novel. That seems a little odd. After all, Yellow Iris, which became Sparkling Cyanide, was published and Mr Curran lists several others. On the whole, Christie's novels are better than her short stories, entertaining though these often are. In that respect she is the opposite of Conan Doyle.

The Incident of the Dog's Ball is not bad but Dumb Witness is excellent if one forgets about the peculiar incident of Captain Hastings and the dog. At the beginning of the novel Hastings explains that he has just come back from Argentina, leaving his wife "Cinderella" Dulcie to manage the ranch while he deals with business matters in England. By the end of the novel he seems to have acquired a dog, settled back into English life an forgotten all about his wife, his ranch and Argentina. (Yet we know from later novels that he does go back. Most mysterious.)

The story does, however, show village life of the period in brisk and amusing fashion as is Christie's wont. In particular she destroys the myth of the wonderful food one could have in country inns and pubs back in the good old days, whenever these might have been. This is what Captain Hastings says:

Little Hemel we found to be a charming village, untouched in the miraculous way that villages can be when they are two miles from a main road. There was a hostelry called The George, and there we had lunch - a bad lunch I regret to say, as is the way at country inns.What wealth of suffering and realism lies in that last phrase.

Here are a few questions to mull over: Which was the largest popular political organization in this country? Which political organization first ensured that membership was open to all classes and people of all incomes? Which political organization involved public activity by women of all classes and in large numbers? Which political organization first had events, both social and educational, for children and young people? [The picture below is of a group of Headington Buds.] Which political organization set up co-operative funds to help those of their members who were less well off?

Here are a few questions to mull over: Which was the largest popular political organization in this country? Which political organization first ensured that membership was open to all classes and people of all incomes? Which political organization involved public activity by women of all classes and in large numbers? Which political organization first had events, both social and educational, for children and young people? [The picture below is of a group of Headington Buds.] Which political organization set up co-operative funds to help those of their members who were less well off?

As the debate about education and its failings rages and as new attempts are made to counter what is seen as the pernicious influence of various educational theories, it is useful to look back on what was said in the past. David Linden, a Ph.D. student at King's College, London, whose interests lie in the modern day Conservative Party looks at a previous educational debate in the sixties and seventies, when the authors of the Black Papers on Education clashed with the educational establishment.

There is always something interesting in History Today. Sometimes it is very little but always something. Today's e-mail brought two links that were worth following up.

Readers of this blog might like to find some more omissions.

If ever there was a conservative writer of detective stories it was Cyril Hare, a.k.a. Alfred Alexander Clark, a County Court judge, even if an aunt of his seems to have been a socialist politician. (Well, a Labour politician, at least, one of the large group of wealthy non-working class socialists, ever present in the Labour Party.)

Many people know what the Whig interpretation of history is, if only in the hilariously parodic version of 1066 And All That, a book I always recommend to anyone who wants a quick summary of English history. (Here is a link to the text but, really, one needs the book in front of one because of the illustrations and because it is easier to shed tears of laughter over a book than in front of a screen.)

Many people know what the Whig interpretation of history is, if only in the hilariously parodic version of 1066 And All That, a book I always recommend to anyone who wants a quick summary of English history. (Here is a link to the text but, really, one needs the book in front of one because of the illustrations and because it is easier to shed tears of laughter over a book than in front of a screen.)

In "The Life and Thought of Herbert Butterfield," Michael Bentley draws on a range of private letters and papers to sharpen our appreciation of Butterfield's actual accomplishments, particularly "The Whig Interpretation of History," the 1931 book that made his reputation by forcing historians to reconsider their discipline. Butterfield argued forcefully against the then-common practice of honing a historical narrative so that it neatly progresses, seemingly inevitably, to the enlightened present or tailoring descriptions of the past to reflect contemporary concerns.While it seems sensible not to stick to the view of history, especially that of England and Britain, being a more or less clearly ascending line towards a sensible and progressive society, it cannot be said that the alternative teaching that has developed since the Whig theory has been abandoned, has been an improvement.

By discarding the apparent linear progression of history schools, teachers and, above all, creators of the national curriculum and examination topics, have discarded all narrative. That, in turn, has meant a loss of understanding as it is impossible to grasp what certain events might mean if the background to them is unknown; and a loss of interest for most pupils. How can one be interested in history if it consists of disconnected topics of varying interest and importance? Ironically, while Butterfield's name is all but unknown these days, Our Island Story, the pre-eminent children's book that was so ably parodied by 1066 And All That, was, on its reprinting, a huge success. As a matter of fact, it is not a very good book and its over-reliance on Shakespeare's plays for information is regrettable. But it gives what many children need: a story in an attractive format with many exciting illustrations.

The review does make one want to read the biography itself, which, clearly deals with the difficult aspects of Butterfield's life while presenting the argument for a reappraisal of his work.

This was advertised in the Conservative History Journal but it is really a National Trust Event though a lecture about Disraeli at Hughenden Manor must be of interest to anyone who is interested in conservative history with either a capital or a small c.

The Immortal Dizzy: Benjamin Disraeli 130 Years On

A special Disraeli celebration lunch to mark the 130th anniversary of his death at which Lord Lexden, the official historian of the Conservative Party and author of a history of the Primrose League, will speak

More Information: the Estate Office, 01494 755573,

hughenden@nationaltrust.org.ukWell, actually I do have some more information: tickets cost £40 each but this will include lunch, a copy of Lord Lexden's history of the Primrose League and a "lavishly" illustrated booklet on which his address at the lunch will be based. All that makes it rather good value, especially if I add the information that Lord Lexden is really Alistair Cooke, who knows more about Conservative Party history than any other man alive.

Event Number 6 on the London Historians site

KENSAL GREEN CEMETERY TOURI have been round a part of that very large cemetery and can thoroughly recommend the tour.

Sunday 18 September 2011, 2pm – 5pm (approx)

Meet at the Anglican Chapel. Nearest Tube: Kensal Green or Ladbroke Grove.

Kensal Green Cemetery is one of the so-called Magnificent Seven – cemeteries which were established in London’s suburbs during the Victorian period in the interests of public health. Notable “residents” include the Brunels (pere and fils), Charles Babbage, Anthony Trollope and many others. We have 12 places booked on the official tour run by the Friends of Kensal Green Cemetery. This means that we’ll have access to the fine chapel and also the catacomb, both of which are normally closed to the public. An extra treat for us is that LH member Sue Bailey, who runs the London Cemeteries blog, will be giving her personal tour after FKGC. There are some very good pubs nearby – we’ll repair to one of these afterwards for drinks.

£7, to include tea and biscuits, pay on the day.

To book your place, please send email to admin@londonhistorians.org with “Kensal Green” in the subject line. Preference will be given to London Historians members in the first instance.

Tory Historian spent the morning at the Tate Gallery or Tate Britain as it is now known and saw The Vorticists exhibition. By no stretch of imagination were the Vorticists conservative but the movement was genuinely exciting and innovative in Britain with real links to Continental art movements (though they refused to be associated with Marinetti and the Futurists). It is, Tory Historian thinks, their refusal to fit in with the rather cosy, attractive and unthreatening modernism of the Bloomsbury Group and surrounding artists together with the soi-disant leader, Wyndham Lewis's hatred for the British Left, the Soviet Union and the Communist fellow travellers that has ensured a certain disdain for him and the group among art critics and historians.

Tory Historian spent the morning at the Tate Gallery or Tate Britain as it is now known and saw The Vorticists exhibition. By no stretch of imagination were the Vorticists conservative but the movement was genuinely exciting and innovative in Britain with real links to Continental art movements (though they refused to be associated with Marinetti and the Futurists). It is, Tory Historian thinks, their refusal to fit in with the rather cosy, attractive and unthreatening modernism of the Bloomsbury Group and surrounding artists together with the soi-disant leader, Wyndham Lewis's hatred for the British Left, the Soviet Union and the Communist fellow travellers that has ensured a certain disdain for him and the group among art critics and historians.

So there is the charge sheet: Wyndham Lewis dismissed the Bloomsbury Group, opposed the Soviet Union, despised the Communist fellow travellers in the West, was pro-American and was an early supporter of Anglospherist ideas. Definitely a fascist, m’lud. The widespread undermining of Wyndham Lewis’s reputation shows the extent to which the Left has managed to control cultural understanding in Britain.

For those who are interested in the extraordinarily important ideas that Adam Smith expressed and detailed in The Wealth of Nations but find it a little hard to get through the lengthy original, Tory Historian can recommend the latest publication by the Adam Smith Institute. It is a condensed version of the great work, with a few original quotations as well as some comments and additions that refer to the more modern period by Dr Eamonn Butler.

That is an odd title for a posting on the Conservative History blog but, let us not forget, that song is now history, though fairly recent, and Bob Dylan is seen as something of a conservative by many.

That is an odd title for a posting on the Conservative History blog but, let us not forget, that song is now history, though fairly recent, and Bob Dylan is seen as something of a conservative by many.

It is surely no secret to anyone who is interested in the politics and satire of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that both used to be a good deal nastier and politicians did not complain when they were accused of all sorts of highly unpleasant, anti-social, disgraceful and, sometimes, illegal activity in the most outspoken fashion. The same went for members of society as a whole.

It is surely no secret to anyone who is interested in the politics and satire of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that both used to be a good deal nastier and politicians did not complain when they were accused of all sorts of highly unpleasant, anti-social, disgraceful and, sometimes, illegal activity in the most outspoken fashion. The same went for members of society as a whole.

An album of 40 ‘suppressed’ cartoons by leading British caricaturist James Gillray (1756-1815) has recently come to light in the Criminal Law Policy Unit of the Ministry of Justice. It features material judged socially unacceptable in the 19th century - including explicitly sexual, scatological and politically outrageous subject matter. The album was probably seized by police more than a century ago as ‘pornographic material’ and handed to Government officials. This slim volume of ‘Curiosa’ has now been transferred to the print collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A.Having seen what was acceptable in those far-off days, Tory Historian is perplexed as to what might have been "unacceptable" enough to have been suppressed and hidden. One can but hope that these "unacceptable" cartoons will be on show though not, perhaps, to politicians who will find them rather unpleasant.

And talking of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tory Historian has also found a note about an exhibition that would have been unthinkable a few decades ago: cartoons and covers from Private Eye on its fiftieth anniversary that is due this autumn. To think that of that naughty satirical magazine that was, for many years, not stocked by W. H. Smith because of fears of libel becoming part of the establishment to the point of being honoured by one of our major museums. How are the mighty fallen. Here is an article in Vanity Fair by Christopher Hitchens.

Links

Followers

Labels

- 1922 Committee (1)

- abolition of slave trade (1)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- academics (2)

- Adam Smith (2)

- advertising (1)

- Agatha Christie (4)

- American history (33)

- ancient history (4)

- Anglo-Boer Wars (1)

- Anglo-Dutch wars (1)

- Anglo-French Entente (1)

- Anglo-Russian Convention (2)

- Anglosphere (19)

- anniversaries (175)

- Anthony Price (1)

- archaelogy (8)

- architecture (8)

- archives (3)

- Argentina (1)

- Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams (1)

- art (14)

- Arthur Ransome (1)

- arts funding (1)

- Attlee (2)

- Australia (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Baroness Park of Monmouth (1)

- battles (11)

- BBC (5)

- Beatrice Hastings (1)

- Bible (3)

- Bill of Rights (1)

- biography (21)

- birthdays (11)

- blogs (10)

- book reviews (8)

- books (78)

- bred and circuses (1)

- British Empire (7)

- British history (1)

- British Library (9)

- British Museum (4)

- buildings (1)

- businesses (1)

- calendars (1)

- Canada (2)

- Canning (1)

- Castlereagh (2)

- cats (1)

- censorship (1)

- Charles Dickens (3)

- Charles I (1)

- Chesterton (1)

- CHG meetings (9)

- children's books (2)

- China (2)

- Chips Channon (4)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (1)

- cities (1)

- City of London (2)

- Civil War (6)

- coalitions (2)

- coffee (1)

- coffee-houses (1)

- Commonwealth (1)

- Communism (15)

- compensations (1)

- Conan Doyle (5)

- conservatism (24)

- Conservative Government (1)

- Conservative historians (4)

- Conservative History Group (10)

- Conservative History Journal (23)

- Conservative Party (25)

- Conservative Party Archives (1)

- Conservative politicians (22)

- Conservative suffragists (5)

- constitution (1)

- cookery (5)

- counterfactualism (1)

- country sports (1)

- cultural propaganda (1)

- culture wars (1)

- Curzon (3)

- Daniel Defoe (2)

- Denmark (1)

- detective fiction (31)

- detectives (19)

- diaries (7)

- dictionaries (1)

- diplomacy (2)

- Disraeli (12)

- documents (1)

- Dorothy L. Sayers (5)

- Dorothy Sayers (5)

- Dostoyevsky (1)

- Duke of Edinburgh (1)

- Duke of Wellington (14)

- East Germany (1)

- Eastern Question (1)

- economic history (1)

- Economist (2)

- economists (2)

- Edmund Burke (7)

- education (3)

- Edward Heath (2)

- elections (5)

- Eliza Acton (1)

- engineering (3)

- English history (56)

- English literature (34)

- enlightenment (3)

- enterprise (1)

- Eric Ambler (1)

- espionage (2)

- European history (4)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- events (22)

- exhibitions (12)

- Falklands (3)

- fascism (1)

- festivals (2)

- films (13)

- food (7)

- foreign policy (3)

- foreign secretaries (2)

- fourth plinth (1)

- France (1)

- Frederick Burnaby (1)

- French history (3)

- French Revolution (1)

- French wars (1)

- funerals (2)

- gardeners (1)

- gardens (3)

- general (17)

- general history (1)

- Geoffrey Howe (2)

- George Orwell (2)

- Georgians (3)

- German history (3)

- Germany (1)

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (1)

- Gibraltar (2)

- Gladstone (2)

- Gordon Riots (1)

- Great Fire of London (1)

- Great Game (4)

- grievances (1)

- Guildhall Library (1)

- Gunpowder Plot (3)

- H. H. Asquith (1)

- Habsbugs (1)

- Hanoverians (1)

- Harold Macmillan (1)

- Hatfield House (1)

- Hayek (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- historians (38)

- historic portraits (6)

- historical dates (10)

- historical fiction (1)

- historiography (5)

- history (3)

- history of science (2)

- history teaching (8)

- History Today (12)

- history writing (1)

- hoaxes (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- House of Commons (10)

- House of Lords (1)

- Human Rights Act (1)

- Hungary (1)

- Ian Gow (1)

- India (2)

- Intelligence (1)

- IRA (2)

- Irish history (1)

- Isabella Beeton (1)

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1)

- Italy (1)

- Jane Austen (1)

- Jill Paton Walsh (1)

- John Buchan (4)

- John Constable (1)

- John Dickson Carr (1)

- John Wycliffe (1)

- Jonathan Swift (1)

- Josephine Tey (1)

- journalists (2)

- journals (2)

- jubilee (1)

- Judaism (1)

- Jules Verne (1)

- Kenneth Minogue (1)

- Korean War (2)

- Labour government (1)

- Labour Party (1)

- Lady Knightley of Fawsley (2)

- Leeds (1)

- legislation (1)

- Leicester (1)

- libel cases (1)

- Liberal-Democrat History Group (1)

- liberalism (2)

- Liberals (1)

- libraries (6)

- literary criticism (2)

- literary magazines (1)

- literature (7)

- local history (2)

- London (14)

- Londonderry family (1)

- Lord Acton (2)

- Lord Alfred Douglas (1)

- Lord Hailsham (1)

- Lord Leighton (1)

- Lord Randolph Churchill (3)

- Lutyens (1)

- magazines (3)

- Magna Carta (7)

- manuscripts (1)

- maps (9)

- Margaret Thatcher (21)

- media (2)

- memoirs (1)

- memorials (3)

- migration (1)

- military careers (1)

- monarchy (12)

- Munich (1)

- Museum of London (1)

- museums (5)

- music (7)

- musicals (1)

- Muslims (1)

- mythology (1)

- Napoleon (3)

- national emblems (1)

- National Portrait Gallery (2)

- nationalism (1)

- naval battles (3)

- Nazi-Soviet Pact (1)

- Nelson Mandela (1)

- Neville Chamberlain (2)

- newsreels (1)

- Norman conquest (1)

- Norman Tebbit (1)

- obituaries (25)

- Oliver Cromwell (1)

- Open House (1)

- operetta (1)

- Oxford (1)

- Palmerston (1)

- Papacy (1)

- Parliament (3)

- Peter the Great (1)

- philosophers (2)

- photography (3)

- poetry (5)

- poets (6)

- Poland (3)

- political thought (8)

- politicians (4)

- popular literature (3)

- portraits (7)

- posters (1)

- President Eisenhower (1)

- prime ministers (27)

- Primrose League (4)

- Princess Lieven (2)

- prizes (3)

- propaganda (8)

- property (3)

- publishing (2)

- Queen Elizabeth II (5)

- Queen Victoria (1)

- quotations (31)

- Regency (2)

- religion (2)

- Richard III (6)

- Robert Peel (1)

- Roman Britain (3)

- Ronald Reagan (4)

- Royal Academy (1)

- royalty (9)

- Rudyard Kipling (1)

- Russia (10)

- Russian history (2)

- Russian literature (1)

- saints (7)

- Salisbury (6)

- Samuel Johnson (1)

- Samuel Pepys (1)

- satire (1)

- scientists (1)

- Scotland (1)

- sensational fiction (1)

- Shakespeare (16)

- shipping (1)

- Sir Alec Douglas-Home (1)

- Sir Charles Napier (1)

- Sir Harold Nicolson (6)

- Sir Laurence Olivier (1)

- Sir Robert Peel (3)

- Sir William Burrell (1)

- Sir Winston Churchill (17)

- social history (2)

- socialism (2)

- Soviet Union (6)

- Spectator (1)

- sport (1)

- spy thrillers (1)

- St George (1)

- St Paul's Cathedral (1)

- Stain (1)

- Stalin (3)

- Stanhope (1)

- statues (4)

- Stuarts (3)

- suffragettes (3)

- Tate Britain (2)

- terrorism (4)

- theatre (4)

- Theresa May (1)

- thirties (2)

- Tibet (1)

- TLS (1)

- Tocqueville (1)

- Tony Benn (1)

- Tories (1)

- trade (1)

- treaties (1)

- Tudors (2)

- Tuesday Night Blogs (1)

- Turkey (3)

- Turner (2)

- TV dramatization (1)

- twentieth century (2)

- UN (1)

- utopianism (1)

- Versailles Treaty (1)

- veterans (2)

- Victorians (13)

- War of Independence (1)

- Wars of the Roses (1)

- Waterloo (5)

- websites (7)

- welfare (1)

- Whigs (4)

- William III (1)

- William Pitt the Younger (4)

- women (11)

- World War I (20)

- World War II (54)

- WWII (1)

- Xenophon (1)

Counters

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(115)

-

▼

December

(9)

- Merry Christmas from Tory Historian

- Tory Historian's blog - Newsreels of the past

- Prime Minister's Questions

- Tory Historian's blog - Quotation from James Madison

- There is a good deal of grievance around

- Tory Historian's blog - C. S. Lewis on impulses

- Tory Historian's blog - Who is to pay for the arts?

- Seventy years ago

- Detective stories are essentially conservative

-

►

November

(14)

- John O'Sullivan reviews Robin Harris

- Anniversary - two important Parliamentary events

- Tory Historian's blog - Happy Thanksgiving

- The teaching of history

- Anniversary - November 22, 1963

- Tory Historian's blog - A great institution

- Events - History in the Pub

- Tory Historian's blog - Duke of Wellington's funeral

- Tory Historian's blog - A terrible anniversary

- John Bew on a great Conservative politician

- Tory Historian's blog - The oldest shop in England

- The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleve...

- Fifty-five years ago

- P. D. James on the essence of detective fiction

-

►

October

(14)

- Exhibitions - Royalist portraits of the Civil War

- Tory Historian's blog - A new Velazquez

- Tory Historian's blog - PMQs at 50

- Fifty-five years ago

- Events - Pevsner and Victorian Architecture

- Trafalgar Day

- Tory Historian's blog - Should historians speak on...

- Tory Historian's blog - The Excitement of Cities

- Tory Historian's blog - Belated Happy Birthday

- Tory Historian's blog - Wyndham Lewis on extremism...

- An interesting article

- Anniversary - Battle of Lepanto

- Events - A promising exhibition

- Tory Historian's blog - Russian food and literature

-

►

September

(9)

- Tory Historian's blog - Independence

- Events - Open House week-end

- Tory Historian's blog- Christie was highly realistic

- Book review - The greatest popular political organ...

- A look back on past educational debates

- Tory Historian's blog - Defiance September 2001

- Tory Historian's blog - Two links from History Today

- Tory Historian's blog - Cyril Hare

- The man who defined Whig history

-

▼

December

(9)